Capturing the Transience of Time - The Photography of Hiroshi Sugimoto

Nov 8, 2017

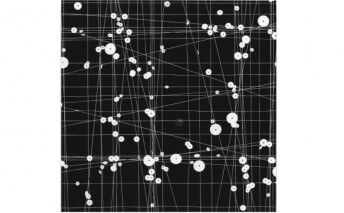

Dual exhibitions going on through 22 December at the Paris and London locations of Marian Goodman Gallery explore the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto, acclaimed photographer, sculptor and conceptual artist, whose work addresses the mysteries of human perception. The London exhibition, titled Snow White, focuses on one body of photographs Sugimoto has been working on since 1978, called his Theater series. Each photograph in the series shows a cinema with screen in the center of the picture. The screen glows bright, like a silver light. To take these pictures, Sugimoto sets up a large-format camera, opens the shutter then keeps the shutter open during the entire film, capturing every frame of the movie on one frame of film. The photographs capture the passage of time, and raise questions about what is real and what is fiction. Meanwhile, the Paris exhibition, titled Surface Tension, focuses on two other bodies of work Sugimoto has been working on. The first is his Seascape series, which he has been developing since 1980. For this series, Sugimoto takes pictures of calm seas all over the world. Every photo is perfectly balanced—half water and half air, with the horizon line in the middle of the picture. And on view alongside the Seascape pictures are five sculptural works from a series called Five Elements. These sculptures consist of five geometric shapes, symbolizing earth, water, fire, air, and emptiness. Each sculpture features an orb, symbolizing water, and each orb contains a photograph from the Seascape series. Both of these exhibitions are must-see. But as with many Sugimoto exhibitions, they only graze the surface of the vast oeuvre this artist has created. So if you are unfamiliar with his work, here are a few more of the many sides of Hiroshi Sugimoto.

See Like a Camera

Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in Tokyo in 1948. He learned to take pictures as a child, but did not consider photography as a career until much later. He studied economics at St. Paul’s University in Japan. But then four years after graduating, Sugimoto moved to Los Angeles and enrolled in graduate courses at the Art Center College of Design. And that same year he had a revelation about the artistic potential for photography to reveal hidden truths about the world. His revelation occurred on a trip to New York City, during which he visited the American Museum of Natural History. The museum is well-known for its dioramas, in which life-sized models of people and animals throughout history are presented amid artifacts of their period. In the background of each diorama is either a photograph or a painting of nature, adding a two-dimensional element to the scene that is obviously fake, and usually somewhat corny.

While staring at one of these dioramas, Sugimoto randomly closed one eye. That made him suddenly realize that by looking at something with just one eye he flattened the entire scene, making it look just as it would if photographed with a camera lens. Looking at the diorama this way made the whole thing look more realistic. So Sugimoto returned to the museum with his camera and took black and white photographs of the dioramas. Amazingly, the photographs flattened all of the elements of the dioramas, not just the background, and the scenes took on an uncanny realness. His Diorama series became the first of many bodies of work he has since pursued that involve rephotographing something, or taking photographs of something that is fake, such as figures in wax museums. When asked in a 2014 interview with Getty Museum Director Timothy Potts about his fascination with this process, Sugimoto said, “Photography is making a copy of reality, but when it is photographed twice it goes back to the reality again. That is my theory.”

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Kegon Waterfall, 1976, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #00.001, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20200)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Kegon Waterfall, 1976, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #00.001, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20200)

What You Are Looking At

Sugimoto followed his Diorama series with his first Theater photographs. Like the Diorama series, the Theater series asked the question of whether what is visible in the photograph is real. If we watch a hollywood movie, we know we are not watching something that actually happened. It is scripted, so it is fake, right? And yet these photographs Sugimoto takes, which contain the visual information of entire films, do capture something that really happened—the screening of the film. The photographs capture reality, a fact underscored in the Drive-In Theater versions of the series, which capture streaks of light in the sky behind the screen as planes fly by throughout the film. So is what we are looking at real or fake? The bright, silver light in the center of the image is not only light—it is a story. And even though it was scripted, it did happen. Like Sugimoto points out, somehow photographing it twice makes it real again.

After beginning his Theater series, Sugimoto embarked on his Seascape series. The imagery in this series is, formally speaking, geometric and abstract. When seen in groups, the images also take on a Typological presence in the tradition of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Although these are not pictures of pictures, as were the images in his earlier Diorama and Theater series, they nonetheless perform a similar function. Sugimoto is showing us pictures of different things that look the same. He shows them to us as they appear at different times of day and in different atmospheric conditions. They are obviously different. But they are also obviously the same. The air and the water are just part of the physical world. But they take on an abstract quality as well. The sea becomes a symbol. And we can again ask what we are looking at. Are these images of the real world or have they dissolved into allegory or metaphor?

Hiroshi Sugimoto - N. Pacific Ocean, Ohkurosaki, 2013, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #582, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20192)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - N. Pacific Ocean, Ohkurosaki, 2013, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #582, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20192)

Images of the World

Sugimoto calls this phenomena of the real dissolving into the unreal, and vice versa, in his work, “a testing method to investigate human perception.” And he has continued this testing method in several fascinating ways over the decades. In the 1990s, he traveled back to Japan and, after wading through seven years of red tape, was allowed to photograph an ancient installation inside of a Buddhist temple called the “Thousand-Armed Merciful Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.” The installation features a multitudinous sculptural representation of Buddha as the physical manifestation of the afterlife. Sugimoto photographed the installation at different times of the day, showing shadows and light illuminating different elements at different times. The resulting series, Sea of Buddha, is an abstract investigation of form and time.

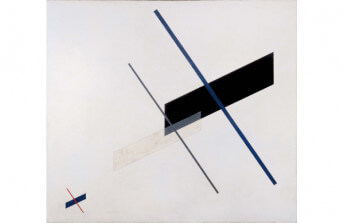

In his Architecture series, also begun in the 1990s, Sugimoto takes completely blurred images of iconic architectural forms, such as the World Trade Center towers and the Eiffel Tower. Meanwhile, for his “Praise of Shadow” series, he lights a candle every night by an open window and takes a single exposure of it burning with the shutter open on his camera the entire time until the candle burns down or blows out. In his Pine Trees series, he took blurred images of perfect pine trees in the Japanese Imperial Palace then collaged them together in surreal compositions comparable to 16th Century Shorinzu “Pine Forest Screens.” All of these series show the real world in a blurred, dreamlike fashion. All of them feature long exposures. They take us back in time, and allow us to connect with ancient, universal visions of architecture, of light, and of nature. They help us see these things as both memories and ideas.

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Salle 37, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #279, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20218)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Salle 37, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #279, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20218)

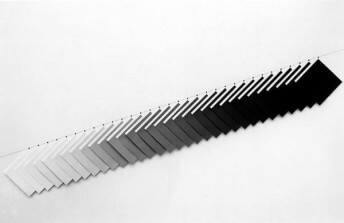

The World in Black and White

In addition to each of these bodies of work already mentioned, Sugimoto also has several other series he is working on, each of which span years, if not decades. In addition to his photography work, he also creates sculptures, engages in performances, and creates site-specific work. All of these things he does seem different and possibly disconnected, but at their heart they can all be understood with the same reasoning Sugimoto uses when he answers the question of why he so often chooses to take photographs in black and white. His answer to that question is, “Credibility is better in black and white than in color.”

Color photographs never capture our true experience of color. So by choosing black and white he makes images that are more abstract, and more universal. That is a variation of the Japanese concept of honka-dori, or imitating the work of another artist. Sugimoto is representing what already exists in various forms, but a perfect copy is not possible, and it is also not preferable. So he shows us reality in abstract form. He is referencing our memories and our communal past. He is, as he puts it, “taking up the melody” as a way of evoking something similar and universal that hopefully everyone can understand.

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Tasman Sea, Rocky Cape, 2016, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #584, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20193)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Tasman Sea, Rocky Cape, 2016, Gelatin silver print, Neg. #584, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in. (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20193)

Featured image: Hiroshi Sugimoto - Paramount Theater, Newark, 2015 Gelatin silver print, Neg. #36.002, Image: 47 x 58 3/4 in. (119.4 x 149.2 cm), Frame: 60 11/16 x 71 3/4 in., (154.2 x 182.2 cm), Edition of 5, (20220)

All images © Hiroshi Sugimoto, Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

By Phillip Barcio