How Much Do You Know About Frank Sinatra’s... Paintings?

This December, a selection of Frank Sinatra paintings will be offered at Sotheby’s New York, in the Lady Blue Eyes: Property of Barbara and Frank Sinatra sale. Not only will the sale include paintings the Sinatras owned, such as a portrait of the singer painted by Norman Rockwell. Mixed in among those works will also be canvasses actually painted by Sinatra himself. Sinatra was a prolific painter. He had a lovely, light filled studio in his home, with windows gazing out at the tops of palm trees. A picture of the studio is printed on the cover of the book A Man and His Art: Frank Sinatra, published in 1991, nine years before Sinatra died. But of course a lot of pop singers refer to themselves as artists. Most use the word loosely—they are not referring to the visual arts. Yet some, like John Cougar Mellencamp or Jason Newsted (of Metallica fame) actually are accomplished painters in addition to their successful music careers. Unlike those two individuals and others like them, Sinatra never tried to cross over into the art field full time. Nor did he claim his painterly accomplishments were brilliant, beautiful, or even original. He sometimes mocked his paintings on stage at his own concerts. And he admitted to his family and friends that the work he made mimicked that of other painters. He copied their styles partly in homage to their genius and partly just because he liked the pictures they made, and he wanted to see what came out when he tried to copy them. Just like me and every artist I have ever drunkenly sang karaoke with, where we inevitably pick at least one Sinatra song to wail at the top of our lungs, Sinatra painted because he liked it. He spent more than 40 years copying the styled of the greatest abstract artists of the 20th Century for the sole reason that it was fun.

Figurative Paintings of Abstraction

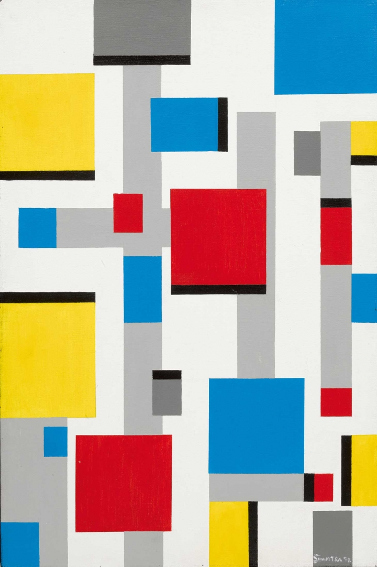

One of the questions people sometimes have about the Frank Sinatra paintings that have been shown in public before is whether or not they should be called abstract. The questions is really, if you look at the work of another abstract artist and then copy it, is that not a realistic depiction of something concrete? Is it not a portrait of something that already exists. For example, one of the paintings that will go under the hammer at Sotheby’s in December is an oil painting Sinatra painted in 1991, called “Abstract After Mondrian.” The picture is not an exact copy of a Mondrian; it is more like a riff on the Mondrian style. It features primary colored squares and rectangles arranged in a sort of loose grid.

Strictly speaking, the hues in this painting actually defy the strict guidelines Mondrian set for his own work. It might better be called “Abstract After van Doesburg.” But that is beside the point. The question is, was Sinatra, like Mondrian, attempting to express universalities through color, shape and line? Was he intending to communicate something on an abstract level? Or was Sinatra simply looking at the design elements of Mondrian paintings and then copying them as an exercise? If so, that makes this paintings decidedly non-abstract—it is more like a figurative example of abstraction. Maybe the difference is negligible. Maybe it is no different than the cover songs Sinatra recorded. In the end, all of the information is in the work itself. If viewers (or in the case of a song, listeners) have an experience that transcends the title or the intent, the work takes on a life of its own. It outlives and rises above its creator.

A Professional Amateur

One of the most endearing things to me about the paintings Sinatra made is that they are unabashedly amateurish. They remind me of a reverse example of what artists like Jean Dubuffet and Jean-Michel Basquiat did. Those artists were professionals. They had extraordinary drawing abilities and control over the marks they made. The figures, shapes, and marks in their paintings might look naive, but if you look closely, every gesture, every color, and every shape reveals their true skill. Painters like that struggle to paint naively. They work hard at forgetting what they knew. Sinatra was the opposite. He admitted he was an amateur and ran with it. The final painting he made was a Hard Edge Geometric work with a blue square inside a red square and two criss-crossing blue lines, all on a yellow background. The edges are not hard, they are wobbly. The shapes are not precisely geometric; they are too sloppy to have that name. The pure fields of color are not pure; the colors are clunkishly mixed, and the brush strokes look like they were done by a care free hand.

Frank Sinatra - Untitled, 1989. 38″ x 42″. Collection of Frank Sinatra

The imprecision of this painting lends it a casual air. That is exactly what I like about it. Even if it is just a figurative copy of the abstract style of another painter, it does indeed convey something abstract to me. It conveys the opposite of whatever it was that Sinatra stood for in the rest of his life. He was driven in his music career, some say to a fault. He worked to defeat anyone who stood in his way, and in the end had a cabinet full of awards, including an Oscar, to show for it. He was one of the most accomplished musicians and film actors ever. And he was always quick to show that he was in control. His paintings reveal a world in which he was not in control. They reveal vulnerability, even weakness. As independent objects of art they may not be anywhere near as impressive as the works of Ellsworth Kelly, Jackson Pollock, or any of the other artists he copied. But as relics left behind by this specific individual, they are precious, occasionally powerful, and always fun.

Featured image: Frank Sinatra - Untitled, 1989. 57″ x 47″, the Desert Hospital, Palm Springs, California

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio