How to Paint Abstract Art? Become a Master.

Before we get started, let’s just make sure everyone’s in the right place. This is a master’s guide on how to paint abstract art. We’ll be skipping the basics like brush techniques, color theory, how to stretch canvas, what lines are and how to draw them, and painting the human figure/still life/landscape/animal/genre scene. We’ll also not cover issues such as who am I, why am I here, why make art, why do anything at all, etc. Also, you should probably already have some basic understanding of art history, say from, oh, cave paintings to the present. Okay then. If we’re all comfortable moving on, let’s begin!

How to Paint Abstract Art – An 8-Step Guide

Step One: Be Talented

This may disappoint some of you. It’s a common fallacy that abstract art is made by artists who can’t draw, have no academic training, or who are just spastic. True, many untrained and untalented people do engage in behaviors that result in paint being applied to surfaces in ways that result in unrecognizable imagery. But while we might call that almost anything else, like passing time, hobbying, using up stuff in the garage, or blowing off steam, what we don’t call it is “painting abstract art.”

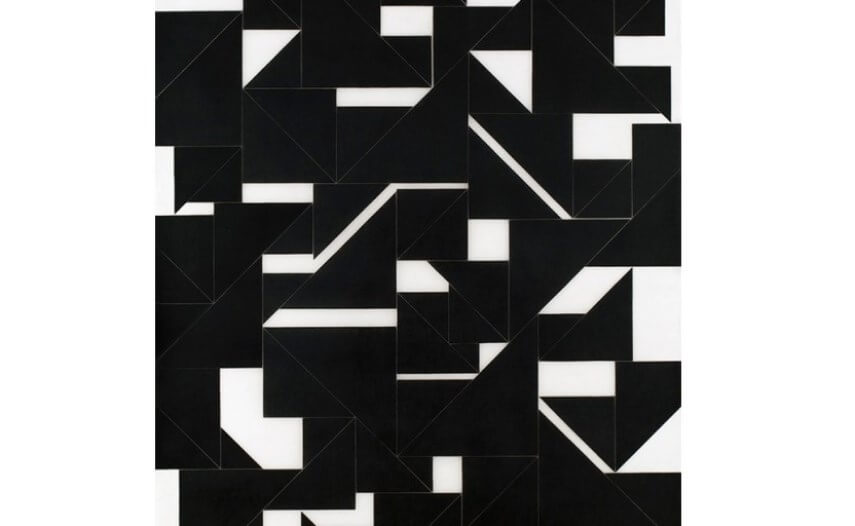

Being an abstract artist is like being a lawyer, or the Prime Minister. It’s a profession. It requires training. You have to work at it full time and be dedicated. Abstract doesn’t mean amateur. Consider the Canadian geometric abstract artist John Monteith. He earned his BA from the Ontario College of Art and Design in 1997. Then after nearly a decade working, exhibiting and publishing he returned to school, earning his MFA from Parsons in New York in 2008. Since then he’s completed residencies in Germany and Switzerland and spent time lecturing and exhibiting around the world. To succeed as an abstract painter, you need a combination of education, focus, stick-to-it-ive-ness, and skill; in other words, talent.

John Monteith - Tableau #3, 2014. 47.2 x 35.4 in

John Monteith - Tableau #3, 2014. 47.2 x 35.4 in

Step Two: Be Intentional

This, too, may come as a disappointment, but yes, even abstract paintings originate with an idea. It’s so much more fun and fashionable to imagine abstract artists as mystical creatures who channel cosmic forces that even they don’t understand, and that their incomprehensible process leads them zombie-like to the canvas where unforeseen powers flow through them without their control, and that the resulting paintings are open to such wild interpretation that any and all meanings heaped upon them are potentially valid.

But even a brief glance at abstract art’s history demonstrates that the opposite is true. Early abstractionists like Wassily Kandinsky and Pablo Picasso were guided by purpose. With scientific dedication they deconstructed painting, isolating elements such as color, line, form, texture, luminosity, gesture, surface and stroke. With intention, they sought ways to use those components to express something universal the way composers use elements like tone, rhythm, meter and key to express abstract universalities through music. Even mystical abstract painters like Hilma Klint and surrealist abstractors like Joan Miró began with concepts and made work informed by ideas.

Richard Caldicott - Untitled #109, 1999. 13.8 x 10.6 in

Richard Caldicott - Untitled #109, 1999. 13.8 x 10.6 in

Step Three: Be Relevant

It’s common for artists today to go directly from high school to university, directly from university to Graduate School, and directly from graduate school to a professional practice. What kind of art is made by a 25-year old who has never worked a full time job, never been fully responsible for paying bills, never maintained a home, managed employees, or generally had to navigate the various debilitating intricacies involved in the modern human struggle for survival?

In order to be a professional, and to have intention in your work, and to be relevant, you must learn about the rest of the humans. See the world. Travel. Read. Learn how to cook. Go to a rally. Stand for something. Change your mind and stand for something else. Learn about what life is like for the other 7 billion people on the planet who might encounter your art. On her professional CV, the Dutch abstract painter José Heerkens lists educational tours of nearly a dozen countries on four continents. These trips directly inform her sense of self and her visual vocabulary, resulting in work that feels layered, modern and global. Understand, abstract art doesn’t have to be “about something,” but it has to be made by someone who is.

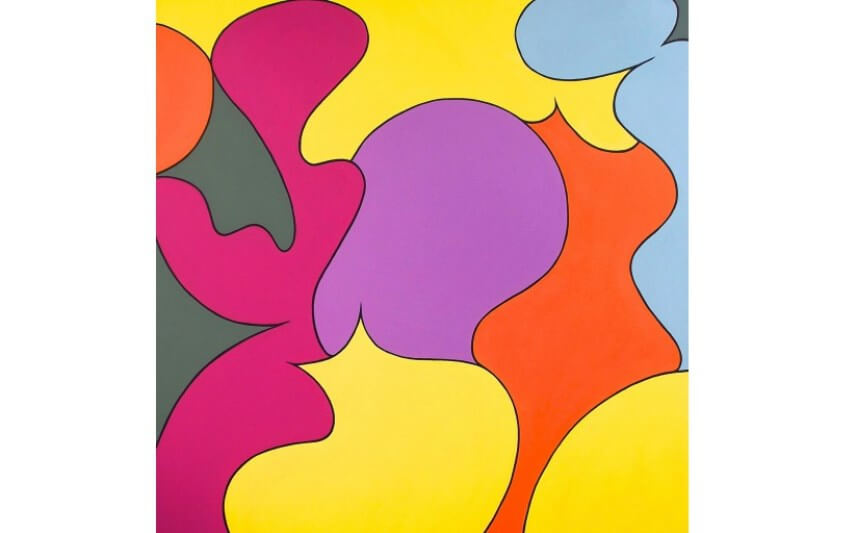

Jessica Snow - Six Color Theorum, 2013. 48 x 48 in

Jessica Snow - Six Color Theorum, 2013. 48 x 48 in

Step Four: Have an Opinion

If you want to be a professional abstract artist, you’ll eventually have to show someone your work. Viewers will ask questions like, “Is this image symbolic of something else, or does it only reference itself?” or, “Was this painting arrived at through the intentionally obfuscation of recognizable objects, or was it the result of intuitive, nonrepresentational gestures?” or, “Why red? Why not blue?” etc.

As a professional artist, you must make a claim on behalf of what you make. Be confident, and sincere. There’s no substitute for intellectual clarity. You don’t have to explain your work, or say what it means or what it’s about. But to refuse to explain your intent, to turn questions back on the viewer, or to say nothing at all is just selfish, and leaves it for others to define your work.

Jeremy Annear - Morning Space, 2008. 47,2 x 63 in

Jeremy Annear - Morning Space, 2008. 47,2 x 63 in

Step Five: Be in Control

When Jackson Pollock’s work was criticized as being chaotic, Pollock’s response was, “No chaos, damn it.” Art isn’t accidental. Unintentional acts are called mistakes. Every mark that ends up on the surface of an abstract painting comes about as the result of the actions and choices of the painter. Even if a painter chooses to set a painting outside in the rain, the resulting watermarks come about as the result of choice.

And if the painter isn’t happy with a mark, the painter can wipe it off, cover it, alter it, or destroy the painting. That’s called editing. You work, you edit, you work some more. Why hide behind the lie of accidents in your work? Abstraction isn’t chaos. Own every mark on every painting. If something happens in the work that you hadn’t consciously planned for, address it. Confront the unplanned event and decide whether to keep it or not. Whatever you decide, and whatever the work becomes, it will be by choice.

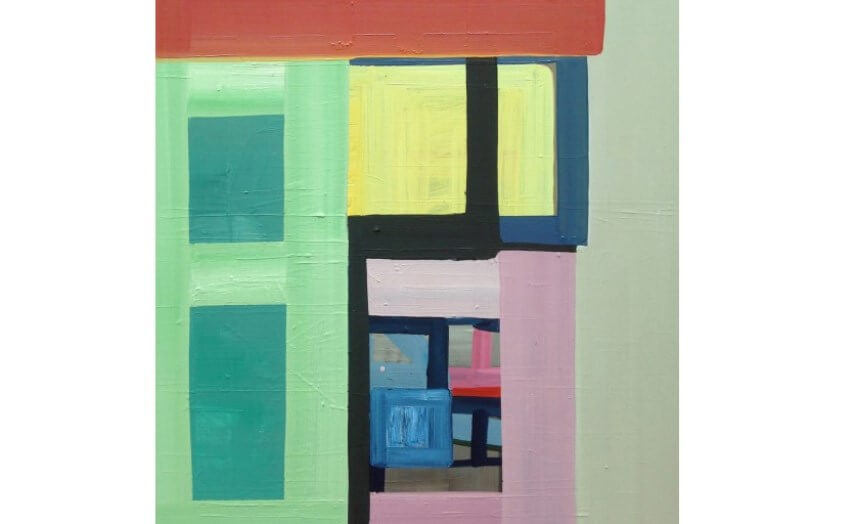

Greet Helsen - O.T, 2014. 27.6 x 39.4 in

Greet Helsen - O.T, 2014. 27.6 x 39.4 in

Step Six: Be Open

Maybe this step seems counterintuitive, given that the past five steps hammered home the importance of being intentional, conceptual, and controlled. We’re not saying to forget all that. We’re just also saying to open up. Connect with your subconscious. Somewhere within your psyche is something universal to every member of the human race. Let your emotions guide your body. Paint viscerally. Put your feelings on the canvas. Even if what you paint is intuitive, primal, unplanned and free, you are still making choices. You still edit. And you still decide when the painting is complete.

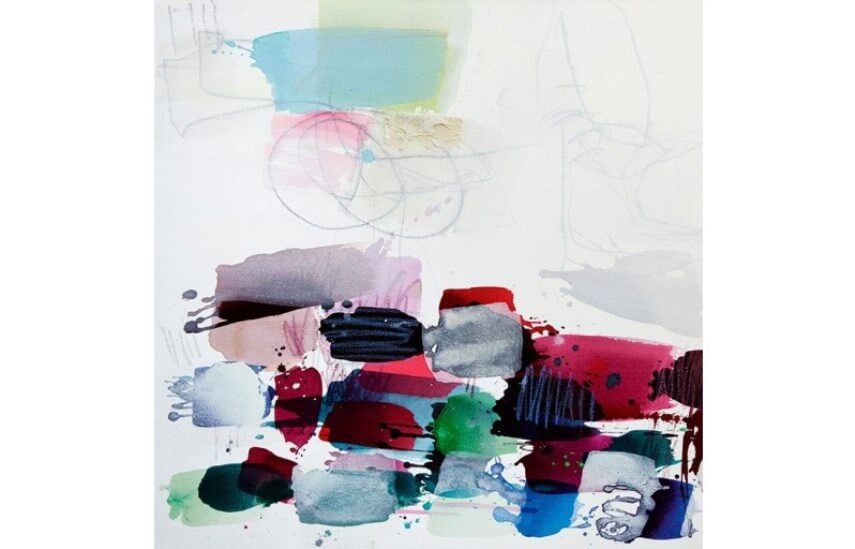

Ashlynn Browning - Stacked, 2014. 43,7 x 39, 8 in

Ashlynn Browning - Stacked, 2014. 43,7 x 39, 8 in

Step Seven: Be Pure

Make yourself a cup of tea. Look in the cup and say out loud, “This is tea.” Now, pour some orange juice into the tea. Look in the cup again and ask yourself, “What is this?” Contemporary artists have access to all of art history. They’re free to explore any style and any medium, and to intermingle styles and mediums in order to find their unique voice and fulfill their conceptual vision. But when styles are mixed together, what are we left with?

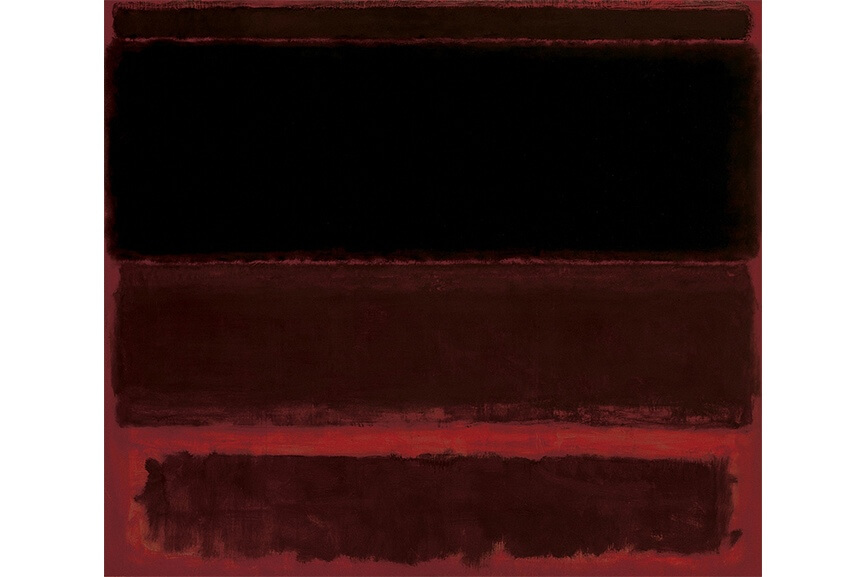

If you paint an abstract monochrome but then paste a collage of reality TV stars over it, is it still abstract? It contains elements of abstraction, but is it the same? Most of us would agree that if you paint a picture of a daisy over the top of a Rothko Color Field painting, it’s like pouring orange juice into your tea. You just end up saying, “What is this?” It means something to call a painting abstract. In order to retain that meaning, purity is key.

Mark Rothko - Four Days in Red, 1958. Oil on canvas. Overall: 101 13/16 × 116 3/8in. (258.6 × 295.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art Collection, New York. Purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz, Mrs. Samuel A. Seaver and Charles Simon. © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mark Rothko - Four Days in Red, 1958. Oil on canvas. Overall: 101 13/16 × 116 3/8in. (258.6 × 295.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art Collection, New York. Purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz, Mrs. Samuel A. Seaver and Charles Simon. © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Step Eight: Be New

Recently we heard a painter describe another painter’s work as “representational paintings of abstract paintings.” Aside from the humor of the statement, it brought up the point that we’re the beneficiaries of more than a century of abstract art, and the great abstract painters of the 20th Century accomplished so much! To rise to the level of those great artists who went before, today’s abstract painters must find ways to make work that is new.

Yes, every painter must confront the need to somehow occupy the surface’s empty space. And of all the demands we’ve made on abstract painters so far, the additional challenge to occupy that empty space with something entirely new might seem the most daunting. But it is this ability to express something fresh and unique that is most vital to abstraction’s future.

If you follow the other seven steps; that is to say if you’re talented, intentional, relevant, have an opinion, remain in control, stay open, and strive to be pure; you’ll not be able to be anything other than honest and true to yourself. And honest self-expression can’t help but lead to something uniquely yours, and by definition, new.

Featured Image: Willem de Kooning - Abstraction, 1949 - 1950. Oil and oleoresin on cardboard. 41 x 49 cm. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © The Willem de Kooning Foundation, New York /VEGAP.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio