The Blue Rhythms of Idris Khan

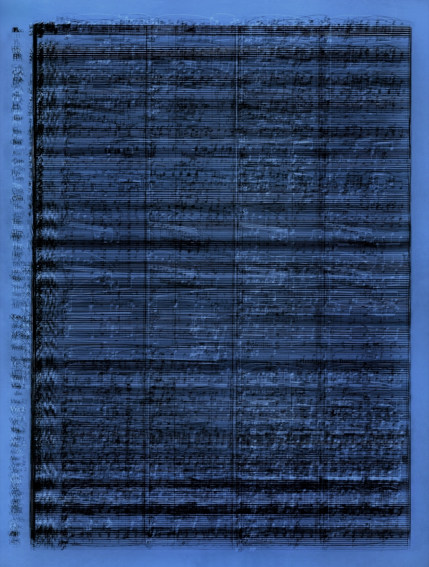

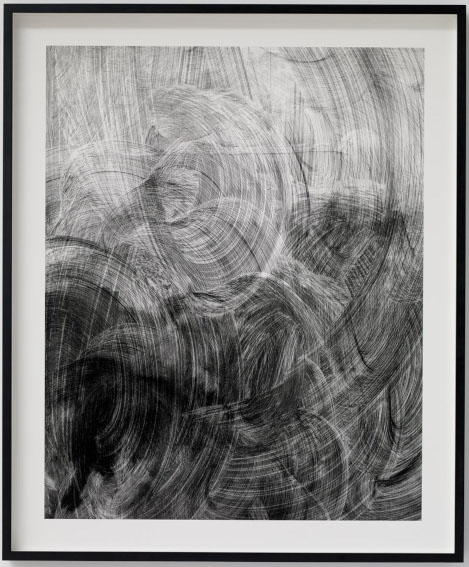

The work of British artist Idris Khan deals with accumulation and compression. Khan accumulates visual content from the material framework of his everyday experiences—photographs of buildings, pages of sheet music, text from books that he is reading—then compresses it into abstract visual compositions. The final works occupy a conceptual space between figuration and abstraction. Take “Pylon” (2014) for example: a photographic print constructed from multiple layered images of an electric power line tower. The source content is figurative, but the finished product is a layered, typological abstraction: a rhythmic, gestural manifestation of line, depth, and tone. This same method underpins Blue Rhythms, an exhibition of new work by Khan that opened earlier this month at Sean Kelly gallery in New York. For some of the works, like “Imprecision of Feelings” (2019), Khan stamped words onto layered sheets of glass with turquoise ink, using the lines of text to create a biomorphic, cosmic, blue explosion. For others, like “The calm is but a wall” (2019), he layered sheets of music over each other until they accumulated into an illegible, blue assemblage of notes and lines and staves. Similarly, for the sculpture “my mother, 59 years” (2019), Khan gathered every photograph he could find of his mother, who died in 2010. He then stacked the photographs and cast the stack out of jesomite. Atop its pedestal, the jesomite sculpture resembles a minimalist, geometric abstract form—something impersonal and self-referential. Yet, like the other works in the show, once you realize the narrative roots of the source material, the work takes on additional dimensions beyond the world of pure abstraction. This tiny statue, for example, is truly a monument to something personal, as well as a statement about how few photographs people used to take of each other compared to today. At the same time as Khan is offering us visually stimulating aesthetic objects, he is forcing us to address the question of what is personal, what is universal, what is narrative, and what is abstract.

The End of Meaning

One of the most infamous works Khan has created was a photograph of every page of the Qur’an stacked atop each other. The image resembles a blurry, generic photostat of a book printed on a copy machine with dirty rollers. Some in the Islamic community wrote that the image is beautiful, and keeps with the tradition of abstraction within Islamic art. Others questioned the eradication of the messages contained within the book. Though the source material Khan used for his newest works is not overtly religious, I would argue that an equally significant debate could be had about its sanctity. Taken at face value, these works are beautiful, and keep with the traditions of Modernist abstraction. But what happens when we consider the countless hours of work that go into composing music, and the subjective individuation and maturation a composer must go through to arrive at the point where such a sophisticated creative act can manifest?

Idris Khan - Lost Happiness, 2019. Digital C print. Image/paper: 93 7/8 x 71 inches (238.4 x 180.3 cm), framed: 101 3/8 x 78 1/2 x 2 3/4 inches (257.5 x 199.4 x 7 cm). Edition of 7 with 2 APs. © Idris Khan. Sean Kelly Gallery.

It could be seen as rather diminishing to reduce an existing musical score to an abstract composition. Why turn something individualized into something generic? Is that the same as colonizing the creative work of another artist—homogenizing it so it can sell? How we answer that question may depend on how we look at the topic of appropriation, or how precious we believe cultural relics to be. As for Khan, there is some hint to his perspective contained within the sculpture he made from photographs of his mother. Each of those photographs was shot on film. Each represents an outlay of money, time and resources. Each also represents a precious moment—an extraordinary place in time when one human saw fit to immortalize the experience of another. When his mother died, whatever precious moments he shared with her were reduced to private memories. All that remained were these pictures. Death is hard to deal with in a direct way. Collecting the photographs then collapsing them into a generic block could be seen as a way of processing loss. The photographs are stripped of old meaning and endowed with new context. They sacrifice their individual humanity, but gain something universal.

Idris Khan - Imprecision of Feelings, 2019. 3 glass sheets stamped with turquoise oil-based ink, aluminum and rubber. 64 15/16 x 55 1/8 x 7 1/8 inches (165 x 140 x 18 cm). © Idris Khan. Sean Kelly Gallery.

Nouveau Synthèse

One of the most aesthetically captivating aspects of Blue Rhythms is the blue hue Khan employs for so many of the works in the show. For anyone familiar with the story of nouveau réalisme, the comparison to Yves Klein Blue is inescapable. In fact, the more you peel back the layers of what Khan is doing with this particular body of work, the more connections to Klein and his associates pop up. According to myth, around 1947 Yves Klein visited the beach with his friends Claude Pascal and Arman. They divided up the world. Arman took earth; Pascal took words; and Klein took the sky. Arman manifested his choice of making art from earth through a series of sculptures he called “accumulations,” which consisted of multiples of the same object combined into a single form. With his blue accumulations of words and music, Khan presents a rather elegant and witty expression of nouveau synthèse, a new synthesis of the ideas of the nouveau realisme pioneers.

Idris Khan - White Windows; September 2016 - May 2018, 2019. Digital fibre print. Image: 50 3/16 x 40 3/16 inches (127.5 x 102.1 cm), paper: 57 5/16 x 47 5/16 inches (145.6 x 120.2 cm), framed: 61 7/16 x 48 7/16 x 2 3/4 inches (156.1 x 123 x 7 cm). Edition of 7 with 2 APs. © Idris Khan. Sean Kelly Gallery.

As with Klein, Arman and Pascal, Khan also seems deeply interested in concocting new strategies for perceiving reality. Visually, his achievements are undeniable. Conceptually they are rich and complex. What is less clear to me about these perceptual interventions, however, is how to relate to them on an emotional level. Despite being drawn to them for their aesthetic power, I personally feel alienated from the works. They ignite a curiosity in me to look deeper into the source materials Khan uses—I want to unravel the layers of the music and listen to the original score; I want to disassemble the text and consider its original wit and wisdom; I want to voyeuristically flip through that original stack of photographs of his mother. But I feel Khan is telling me not to fall into the web of personalization and subjectivity. The beauty he is trying to show me is not the beauty of the individual, it is the beauty of the collective.

Featured image: Idris Khan - The calm is but a wall, 2019. Digital C print. Image/paper: 71 x 113 3/4 inches (180.3 x 288.9 cm), framed: 78 1/2 x 121 1/4 x 2 3/4 inches (199.4 x 308 x 7 cm). Edition of 7 with 2 APs. © Idris Khan. Sean Kelly Gallery.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio