James Siena – Not Your Typical Abstract Artist

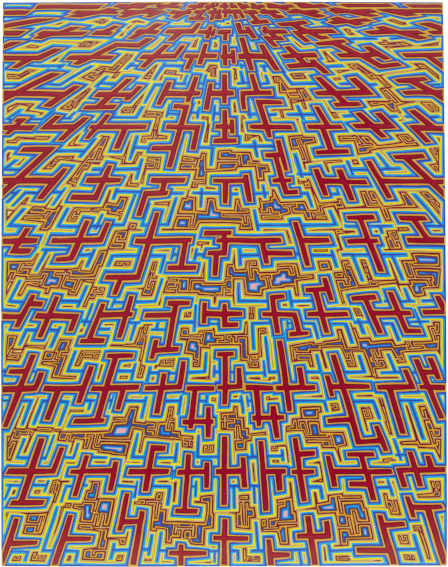

To look at a James Siena painting is to get pulled into a sinuous, methodical maze of color and lines. There is no picture at which to look. Instead, there is a transcendental zone in which to wander. Surface, space and light meld together into visual vibrations until the mind is forced to choose between analyses and acceptance. The straightforward act of patient looking is rarely so gratuitously rewarded. If looking at these tangles of color and line is hypnotic, imagine painting them. The laboriousness involved, especially in the recent large-scale works Siena has made, is hard to imagine. Picturing Siena lording over one of his surfaces adding line after line reminds me quite a bit of “A Line Made By Walking” (1967), one of the earliest Land Art works by British sculptor Richard Long. To make it, Long walked repeatedly back and forth across the same patch of grass. He later recalled, “I wanted to make nature the subject of my work, but in new ways. My first work made by walking was a straight line in a grass field, which was also my own path, going ‘nowhere’.” In a way, Siena is making lines that go nowhere, and in the process, like Long, he is drawing less attention to the finished work itself, and more attention to the planning and human labor that is involved in its making. Similarly, the sinewy compositions Siena creates evoke connections to the masterpiece of Alberto Burri, his “Grande Cretto.” Carved into the surface of the planet itself, its maze of linear cracks forces viewers to choose: they can either walk through them or stand far enough away to look at them. The two experiences are totally different, and mutually exclusive. Likewise, we can stand back and stare at a James Siena painting, or we can walk up close to it and attempt to navigate its linear tangles. The experiences are nothing alike, although both hold the possibility of pure delight.

Thinking and Feeling

Siena talks about his painting practice in two separate terms: provoking thought, and inducing feeling. For the viewer, the dichotomy is obvious. The lines and shapes we see confound any resemblance to reality, and yet we cannot help but think about what they might be, what they might represent, or what they might mean. We think about how they were made, and what they are made of. At the same time, we become tired of thinking. When we simply allow ourselves to feel, we start to believe there is more going on than cognition can recognize. The feeling of the patterns exerts itself—it can be harmonious, or it can be dissonant. The feeling of the color relationships bring us into confluence with unknown forces—they can bring joy, or maybe repulsion. In this state of half thinking and half feeling, we have a chance of just letting go. Looking into the painting, or through it, as we might with a Rothko Color Field, offers a release that is pure pleasure.

James Siena - Tanagra, 2006. Lithograph. Composition (irreg.): 28 7/8 x 43 3/16" (73.4 x 109.7 cm); sheet: 29 1/2 x 43 7/8" (75 x 111.4 cm). Universal Limited Art Editions, Bay Shore, NY. Gift of Emily Fisher Landau. MoMA Collection. © 2019 James Siena

Yet when he talks about the difference between thinking and feeling, Siena is not only talking about us, the viewers. He is also referring to his own artistic method. It may not seem like it, but each of his paintings is planned out ahead of time—he devises a system that determines the structure of the composition, what he calls a “visual algorithm.” Siena follows this system until the painting completes itself. That is the thinking phase. Yet the process is inevitably altered by the limitations of his mind and body. The plan might be mechanical, but he, as an artist, is not. His hands cannot perform with the same level of exactitude as a machine, nor can his mind stay perfectly focused throughout the process of making a painting. The work is a collaboration between plan and action; between the forethought of an algorithm and the substitutions demanded by human frailty. Hanging in the balance is an abstract commentary on our time: the end of the age of information, and the dawn of the age of imagination.

James Siena - Twelve-Lobed Sawtoothed Non-Organism, 2013. Enamel on aluminum. 19 1/4 x 15 1/8”. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery. Photo by Tom Barratt.

Making and Working

One of the difficulties I sometimes encounter when looking at a James Siena painting is sensing when and where to halt my gaze. No part of the picture ever stands out as a focal point. There is no subject, there is only matter. This is a testament to the dedication Siena has to the continuum of work. He has spoken in the past about time, and the notion that when you are involved in a process that takes time, every second is as important as every other second. He imbues his paintings with that same philosophy, but in a visual sense. The picture is a record of time. No moment in the creation of the work was more important than any other moment, and no element of the picture asserts itself as more important than any other element, although each is unique.

James Siena - Dr. Michelle Carlson, 2011-2014. Enamel on aluminum. 19-1/4″ x 15-1/4″. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery. © 2019 James Siena

The continuum of his work passes over into the continuum of his practice, as Siena prolifically moves from one painting to the next. His furious output has pushed him to evolve into making larger paintings with more complex patterns, but the fundamentals of his method endure. His increasing complexity shows maturity, and dedication. For an artist to do the same thing over and over again is difficult, varying an action in ever so subtle ways and yet staying true to the concept of repetition. Imagination and inventiveness must be found in ever more nuanced places. An artist like Siena who uses no assistants must not ask why these lines are being made, nor why these systems are being invented, but he must simply delight in the making and the inventing. Similarly, for viewers to embark on the contemplation of such works requires equal devotion to simplicity, equal dedication to imagination, and equal openness to delight.

Featured image: James Siena - Coalition, 2011. Eleven-color lithograph. 22.50 x 18.00 in (57.1 x 45.7 cm). Edition of 21. © 2019 James Siena

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio