Jean Tinguely and His Metamechanics

We each have our own unique relationship with machines. Some of us relate to machines with gratitude, joyfully relying on them for their efficient, utilitarian services. Others of us use them only begrudgingly when there’s no other option. The Swiss artist Jean Tinguely devoted his entire career to exploring the concept of machines as sculpture. He created abstract mechanical contraptions, which he invited viewers to interact with on an aesthetic, experiential level. He called his creations Metamechanics, Meta coming from Greek, referring to something that’s self-referential. By creating machinery that was not intended to do work, produce products or perform any utilitarian function whatsoever he expanded the definition of what sculpture could be, and offered viewers a chance to re-contextualize the machine age from a purely aesthetic viewpoint.

Detached Elements

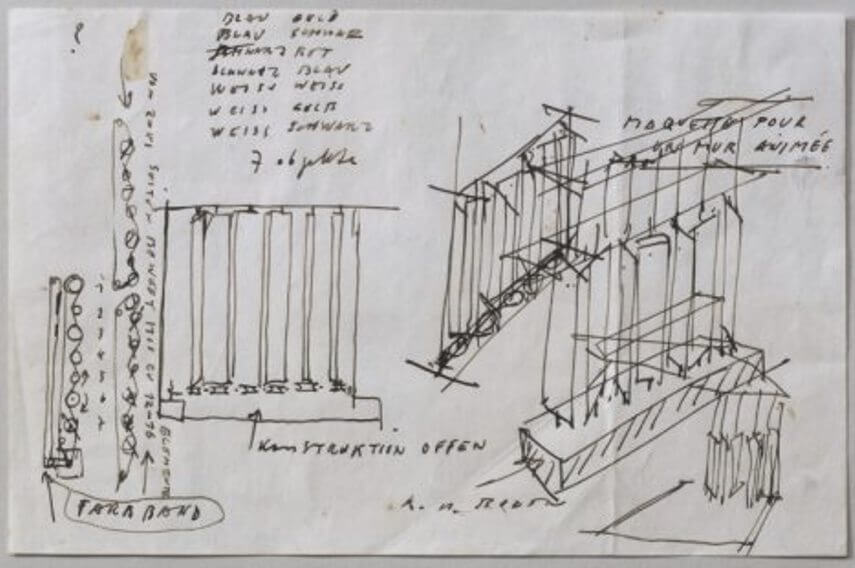

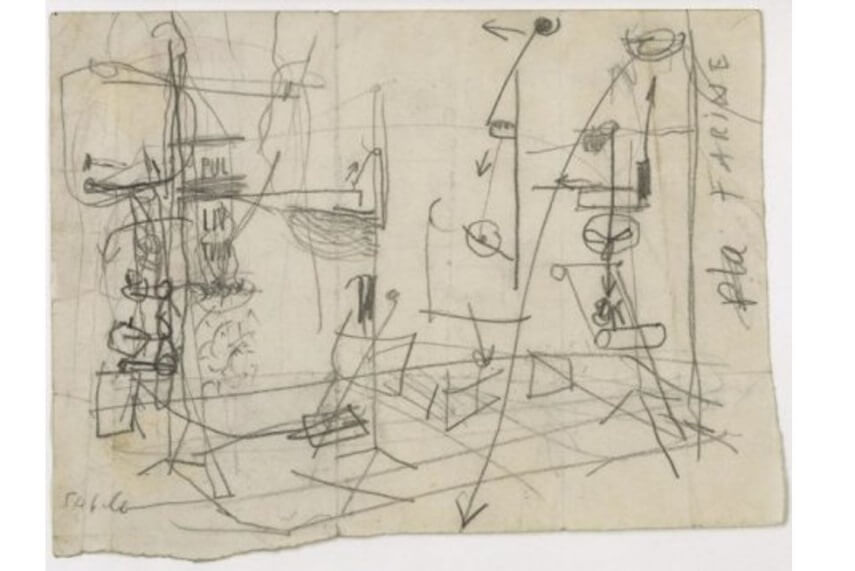

Tinguely’s earliest mechanical sculptures were made in the 1950s, and were simple kinetic reliefs designed to hang on the wall. They were made from thin wires and gears that rotated. Their simplicity reflected Tinguely’s effort to deconstruct the building blocks of machines. Sketches he was making at the time, some of which are in the possession of Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland, reveal a glimpse of his mental process. He was isolating mechanical elements and abstracting them, in a way similar to abstract painters isolating formal elements such as color, line, surface, plane and form.

A sketch by Jean Tinguely of mechanical functions and movements, c.1954. © Jean Tinguely

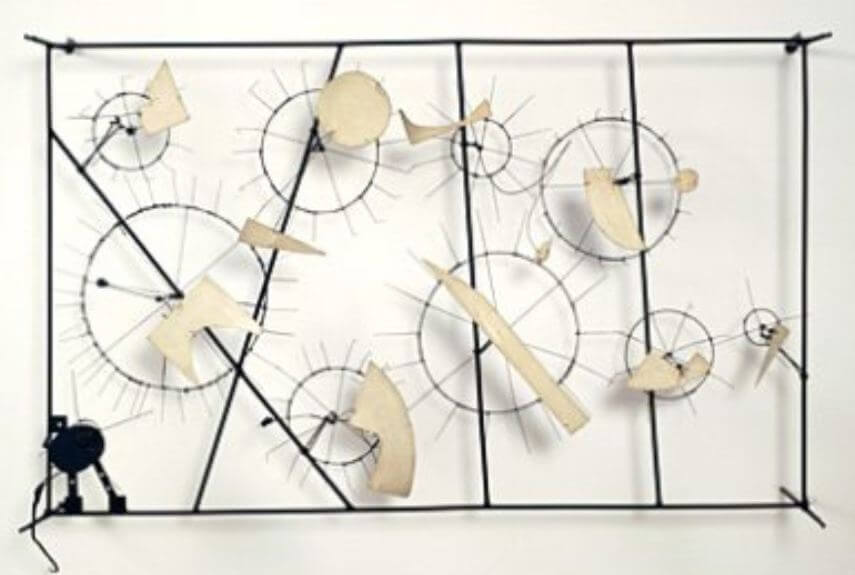

He then added elements to his reliefs that complicated their meaning and functionality. In a series of works he called Élément Détaché, he cut out abstract shapes from Pavatex, an industrial wood fiber product, then painted the shapes and attached one to the center of each of the work’s gears. When the work of art was moved, touched or interacted with in any way it became kinetic as the abstract painted shapes moved about on the gears.

Jean Tinguely - Élément Détaché I, Relief méta-mécanique, 1954, 81 x 131 x 35.5 cm. © Jean Tinguely

Rise of the Méta-Mécanique

Tinguely soon took his simple pieces to the next level, adding a multitude of functions and mechanized elements and bringing them off the wall and into three-dimensional space. He left machines in a state of imperfection that would allow them to be easily transformed by various stimuli. He often included imagery in the machines that related to other artists, and used the artists’ names in the pieces’ titles. For example, his wall relief Meta-Kandinsky, which includes imagery that references Wassily Kandinsky’s abstract paintings, and the Méta-Mécanique sculpture Méta-Herbin, which references the abstract geometric paintings of Auguste Herbin.

Jean Tinguely’s early Metamechanical artworks had much in common with the work of other kinetic artists such as Alexander Calder. But he quickly and wildly expanded the range of his creations, taking them into the realm of the conceptual. A perfect example is Frigo Duchamp, created in 1960. For this piece, Tinguely installed an electric motor, an air siren and an 110V electric motor into the belly of a Frigidaire refrigerator. The title might at first seem like a reference to Dadaism, but the simpler explanation is offered by the fact that the refrigerator was actually a gift to Tinguely from Duchamp.

Jean Tinguely - project sketch for Homage to New York, 1960. © Jean Tinguely

Jean Tinguely and The New Realism

Tinguely was one of the artists who signed the manifesto of Nouveau Réalisme in 1960. This movement, which was co-founded by the conceptual artist Yves Klein, was dedicated to exploring “new ways of perceiving the real.” Reality for most people at the time was dominated by drastic changes such as global technological advances, rising social disparities, rapidly expanding cities, mass transportation, and the constant specter of war and nuclear annihilation. Machines were at the heart of each of these changes.

Tinguely’s conceptual contribution to new realism was to make art that tried to address the purpose and function of machines. Said Tinguely, “Art is the distortion of an unendurable reality... Art is correction, modification of a situation.” He built mechanized pieces that were made largely from society’s junk, and which performed no utilitarian function. These useless, abstract artworks were self-referential, often hideously deformed-looking, and prone to breaking down. As the world understood mechanics, they were the opposite of machines.

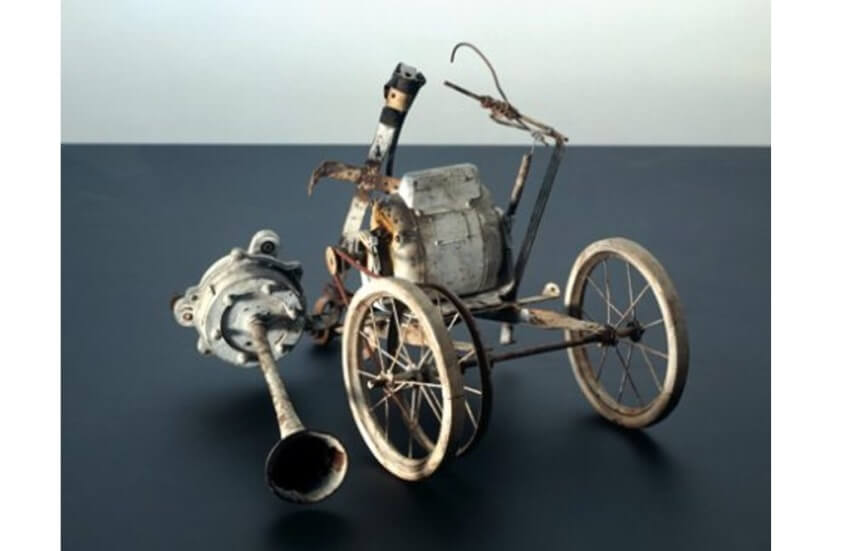

Jean Tinguely - a surviving piece of the destroyed sculpture. © Jean Tinguely

The Art of Self-Destruction

Also in 1960, the same year that Jean Tinguely signed the manifesto of New Realism, he created what has become his most famous artwork, a happening involving a self-destroying monumental sculpture titled Homage to New York. For the event, Tinguely constructed a massive Metamechanic sculpture on site in the sculpture garden of New York’s MoMA. The sculpture was a piecemeal Frankenstein of bicycle tires, gears, electronics, motors and junked machine parts. Fellow artists Billy Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg also contributed elements to the happening, such as an auxiliary machine that shot out money into the crowd.

For 27 minutes, Homage to New York chugged and whirred, before eventually belching smoke and bursting into flame. As fire and destruction consumed the piece, members of the viewing audience were invited to collect the smoldering fragments to take home. The fire department was finally brought in to extinguish the fire, and most of the remaining pieces were discarded. Only a couple of remnants of the machine remain.

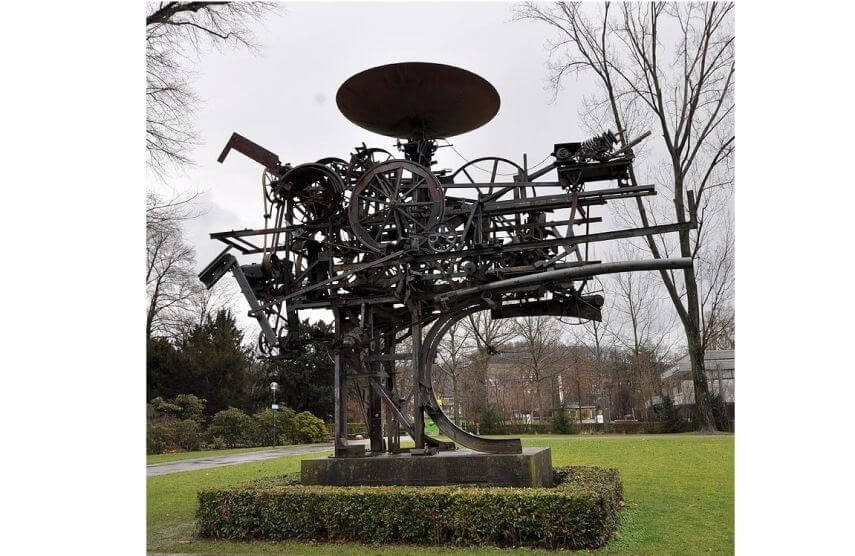

Throughout the next three decades, Tinguely gained prominence with a series of monumental abstract, public Metamechanic pieces. The first, created in Zürich in 1964, was a massive, purposeless machine called Heureka, after the Greek eureka, meaning, “I’ve found it.” In 1970, Tinguely created an even more massive indoor sculpture in Columbus, Indiana, called Chaos I, constructing it entirely from local metal, some new and some from scrap. Chaos I is designed to run quietly most of the time, occasionally bursting out in loud, cacophonic noises.

Jean Tinguely - Heureka in Zürich, Switzerland. © Jean Tinguely

Beyond Purposelessness

In the mid-1960s, Tinguely began creatively collaborating with the woman who eventually became his wife, the sculptor Niki de Saint Phall. Like Tinguely, Saint Phall made highly conceptual work, though less abstract and more socially concerned. As Tinguely became inspired by Saint Phall, his work took on subtly different characteristics. He made a series of fountains that were decidedly functional, marking a conceptual departure from the purposelessness of his previous works. His most famous fountain, a collaboration with Saint Phall, is the Stravinsky Fountain outside of the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

In the 1980s, Tinguely made several deeply personal, emotional works. He created artworks named in honor of the philosophers that had influenced him. After a deadly fire at a neighbor’s farm, he somberly collected remnants from the aftermath, assembling them into a memorial installation titled Mengele - Totentanz, after a name imprinted on one of the corn processing machines destroyed in the blaze. One of Tinguely’s most touching memorials is The Final Collaboration with Yves Klein, which IdeelArt wrote about when the piece was exhibited at the Venet Foundation in September 2015.

Though these memorial installations and fountains contained the same mechanical nature and abstract visual language as his earlier works, their titles, subject matter and function greatly affect the viewer’s perception of meaning, making them far less abstract. As abstraction gave way to meaning and purposelessness gave way to use, Tinguely didn’t abandon his big idea; he fulfilled it. He redefined the role of machines in the culture. He defined them as aesthetic tools that help people perform what may be their own most important task, communicating to each other the content of their hearts.

Feature Image: Jean Tinguely - Meta-Kandinsky, 1956, wall relief (left) and his Méta-mechanical piece Méta-Herbin, 1955 (right). © Jean Tinguely

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio