What is Abstract in the Work of John Baldessari

Oct 4, 2016

While teaching at the University of California San Diego, the artist John Baldessari developed an assignment to challenge the attitude his students had about abstract art. He told them to pick out “the most maddening piece of art that they could find, that they thought would have the least to do with reality.” He then sent them out with a camera and instructions to find the equivalent of that artwork in the real world. The students succeeded in almost every instance. What does that say about the integrity and sanctity of an abstract image? What questions does it raise about why one thing is considered art and another almost identical thing not? As Baldessari puts it, “it’s just how you see the world. It’s not about art not being real in any way.” The exercise was about challenging the attitude of the students. Abstraction is just a word, and words themselves are abstract. Whether something is considered abstract, conceptual, objective, serious or satirical has as much to do with context as aesthetics. And what is even more important is perception. What ultimately defines the nature of any work of art depends entirely on your point of view.

Words Are Pictures

John Baldessari has contributed to some of the most experimental and influential art programs in the United States. As an artist, he has earned a reputation as an innovator whose work constantly evolves. One profound way Baldessari has influenced the current generation of contemporary artists is through his dedication to an omni-disciplinary approach to making art. He is open to working in any and all mediums in order to keep his work interesting. This approach grows naturally out of his personal belief that he should always strive to see the world in new ways.

A key issue Baldessari has addressed throughout his oeuvre is the weight humans give to images versus words. Since the 1960s he has explored novel ways of juxtaposing images and words. What he has discovered is that when language is placed out of context beside an image, the meaning of both can change in profound and surprising ways. The cliché that pictures are worth a thousand words is off. Baldessari has proven that when it comes to meaning and understanding, pictures and words have equal weight.

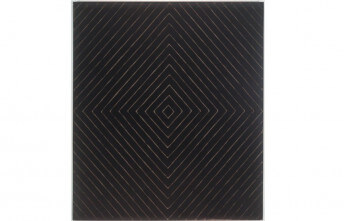

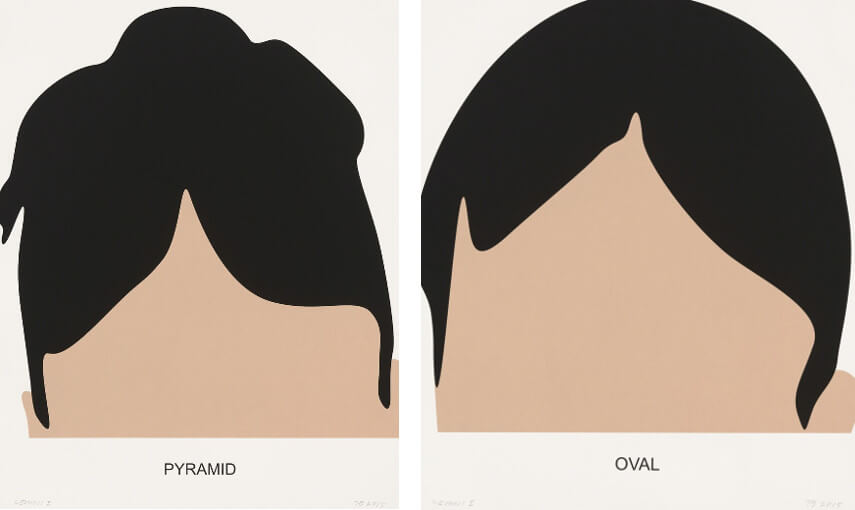

John Baldessari – Pyramid, 2016. 3 color screenprint. 46 × 36 in. 116.8 × 91.4 cm. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles (Left) / John Baldessari - Oval, 2016. 3 color screenprint. 42 1/2 × 36 in. 108 × 91.4 cm. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles (Right). © John Baldessari

John Baldessari – Pyramid, 2016. 3 color screenprint. 46 × 36 in. 116.8 × 91.4 cm. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles (Left) / John Baldessari - Oval, 2016. 3 color screenprint. 42 1/2 × 36 in. 108 × 91.4 cm. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles (Right). © John Baldessari

The Cremation

Before he discovered his mature style, Baldessari was a traditional painter who excelled at life drawing. He began taking university art classes in 1949, studying various perspectives (art history, art education, studio art) at various schools (UC Berkeley, UCLA, Otis, Chouinard) for more than ten years. Throughout that time, and for the next decade after school, he followed roughly the same approach to making art: he painted images on canvases. But one day in his studio he took inventory of his work. Lining his canvases up against the wall he had an epiphany: his works were all the same in some essential way, and were similarly the same as all pieces ever painted.

He wanted to move forward. But he realized that in order to do that he would have to change in a fundamental way. He decided to destroy all of his existing work. Calling it The Cremation Project, Baldessari hired a cremator and burned everything except a few of what he considered his most forward-thinking pieces. He found a gallery to let him hold an exhibition of The Cremation Project after hours. The exhibition featured some of the ashes baked into cookies displayed along with the cookie recipe, as well as memorial plaques documenting the birth and death dates of the artworks. So began the omni-disciplinary phase of his career.

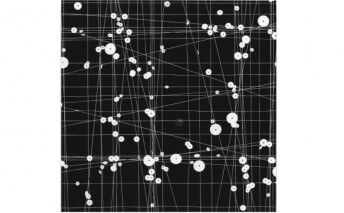

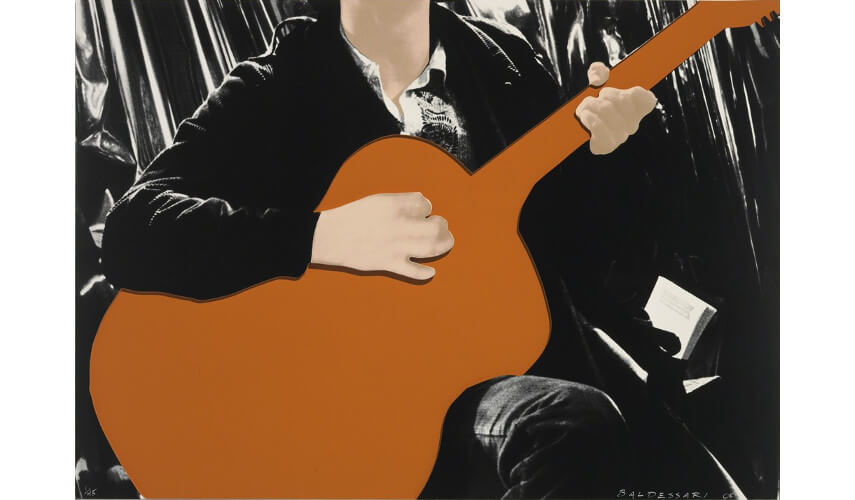

John Baldessari – Person With Guitar (Orange), 2004. 3-layer, 5-color screenprint construction (mounted to sintra and hand cut). Framed: 33 x 44 1/2 x 3 in. 83.8 x 113 x 7.6 cm. Edition of 45. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles. © John Baldessari

John Baldessari – Person With Guitar (Orange), 2004. 3-layer, 5-color screenprint construction (mounted to sintra and hand cut). Framed: 33 x 44 1/2 x 3 in. 83.8 x 113 x 7.6 cm. Edition of 45. Gemini G.E.L. Los Angeles. © John Baldessari

Everywhere Signs

The few works John Baldessari saved from cremation were some of the conceptual, text-based paintings he had been making, which featured sentences or phrases referencing painting or art history. He intended these works to draw attention to the absurdity of self-referential art commentary. But something about the way he painted them was causing them to be perceived more as personal statements. So rather than painting his next sign paintings himself, Baldessari hired professional sign painters to paint them. This choice referenced Minimalist ideas about removing the ego of the artist, while simultaneously questioning the seriousness of such academic ideas.

Continuing this line of thought, Baldessari next designed a series of representational pieces that he hired the sign painters to paint. Taking a cue from the artist Al Held, who had criticized conceptual art by saying that it is “just pointing at things,” Baldessari had the sign painters paint images of hands pointing at things. He then gave credit to the sign painters by signing their name to the canvases beneath the pictures. These works questioned the role of the artist in the art making process and also challenged the difference between fine and functional art. On an abstract level, the fingers pointed at something banal, drawing attention to that thing rather than to the myriad other formal qualities and conceptual notions occurring in the work.

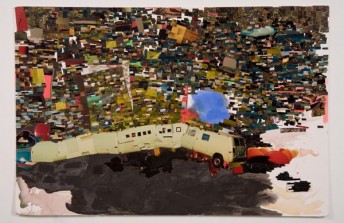

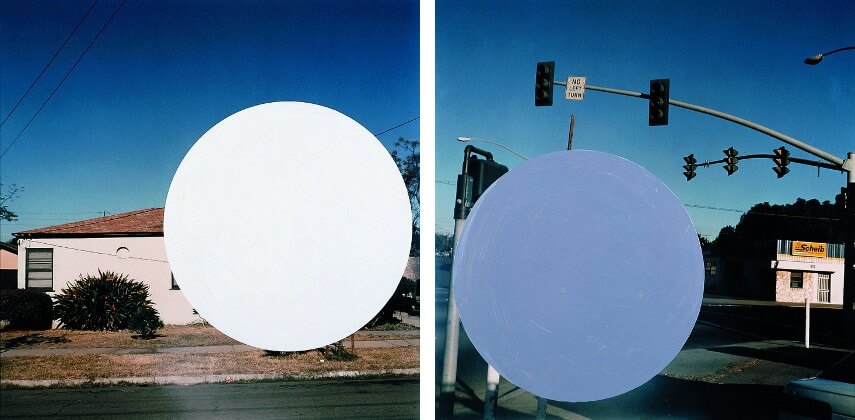

John Baldessari - National City (W), 1996-2009. Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York (Left) / John Baldessari - National City (4), 1996-2009. Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York (Right). © John Baldessari

John Baldessari - National City (W), 1996-2009. Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York (Left) / John Baldessari - National City (4), 1996-2009. Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York (Right). © John Baldessari

Moving Pictures

In the 1970s John Baldessari began working with film as a medium. The first work he made was called “I Am Making Art.” In the film he waved his empty arms like a painter, making gestural motions as though working on a canvas, all the while repeating, “I am making art.” The film seems to be making fun of painting as an empty gesture. But the performance itself could be perceived as art, and so could the film. On an abstract level it raises many concerns, such as whether art exists in the idea, in the execution or in the relic, and whether just saying something is art makes it so.

In addition to making his own films, John Baldessari also often appropriates elements of existing film rolls. Sometimes he cuts it into pieces and places the stills together into new configurations. Other times he places a still frame from a movie beside a section of unrelated script. The new narratives that emerge through this process seem simultaneously cohesive and shattered. They are entirely informed by individual viewers, who each must draw their own associations between the images and words based on pre-existing points of view.

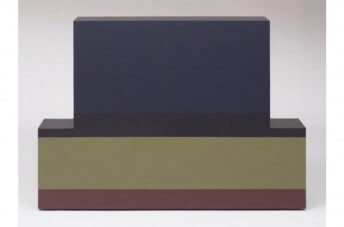

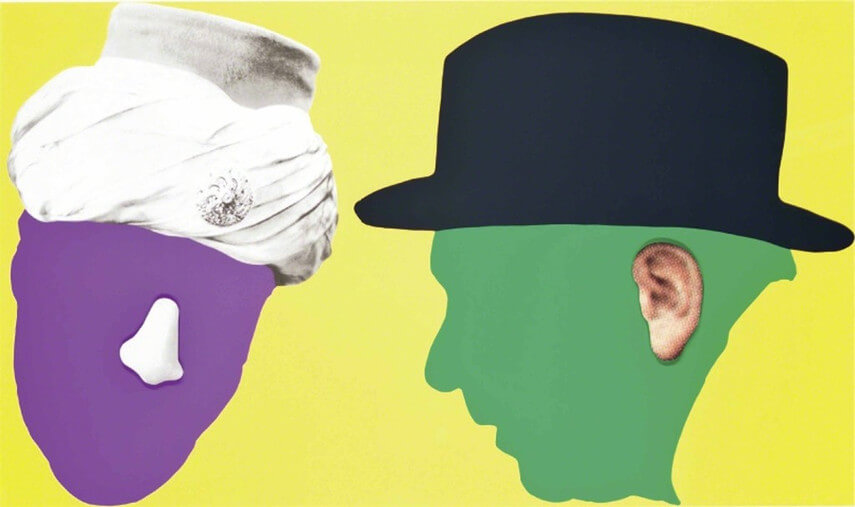

John Baldessari – Two Profiles, One with Nose and Turban; One with Ear and Hat, from Noses and Ears, Etc, The Gemini Series, 2006. Screenprint in colors on Rives BFK and Lanaquarelle paper mounted to Sintra. 30 × 52 in. 76.2 × 132.1 cm. Edition of 45. Collectors Contemporary, Singapore. © John Baldessari

John Baldessari – Two Profiles, One with Nose and Turban; One with Ear and Hat, from Noses and Ears, Etc, The Gemini Series, 2006. Screenprint in colors on Rives BFK and Lanaquarelle paper mounted to Sintra. 30 × 52 in. 76.2 × 132.1 cm. Edition of 45. Collectors Contemporary, Singapore. © John Baldessari

Empty Spaces

In one of his most famous bodies of work, John Baldessari alters found photographs by covering or painting out elements of the images. Baldessari was inspired to explore this idea after noticing how museums used unpainted plaster to fill the cracks and holes in ancient pottery. He became interested in the missing spaces in the imagery. He found some colored dot stickers, the type used to make price tags for a garage sale, and began using them to cover faces and other points of interest in photographs in order to change the way the images might be perceived.

In these works, we experience the mature expression of the effort Baldessari makes to challenge our point of view. The filled-in spaces make images of things like celebrations seem generic. Special moments seem cliché. Scenes deemed valuable enough by someone to capture permanently become anonymous and mundane. These altered images eloquently explore the abstract psychological effects that can occur in a viewer when what was visible becomes hidden. While their meaning is ambiguous, they succinctly, if abstractly, express a larger concern, one that John Baldessari has long had: to challenge conventions and expand the perception of everyone who encounters his art.

Featured image: John Baldessari – artwork from John Baldessari Does Not Make Boring Art Anymore series, 2007. © John Baldessari

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio