Abstraction is in the Physical - Jules Olitski

The career of the Ukrainian-American artist Jules Olitski (1922 – 2007) reminds us that art is not a fixed human endeavor, which has to be done the same way by every practitioner, like, say, flying a passenger airplane. Artists are-or should be-completely free to re-invent the field as often as they want. Olitski was only guided by one factor: his intuition. He would have a vision of an image, or a sensation he wanted to capture, or a material presence he wanted to manifest, and would set about trying to make it happen. Whether his vision fit with trends or tastes did not matter. Most people call his work abstract, but he, himself, did not make that distinction, perhaps because his particular vision for a painting was, to him, its own sort of subject matter. If one dreams of painting a spray of color hanging in the air, then paints a painting which realizes that dream, that painting is exactly what it describes: a painting of a spray of color hanging in the air. How much more concrete can you get? On the topic of advice to other artists, Olitski once said, “Expect nothing. Do your work. Celebrate!” He may have given similar advice to his viewers: “Expect nothing. Look at the work. Celebrate!” Yet, art appreciation is a separate pleasure from art criticism. Critics, historians, and art dealers have long had difficulty knowing exactly where to place Olitski within the linear fairytale known as art history, maybe because Olitski never bothered to ask himself where he fit in. He switched styles and mediums and methods so often that he is not only hard to historicize, but he is hard to commodify, since so many collectors want to be able to talk about the artists they collect in terms of a convenient short-hand: “This is the grid painter. This is the lady who did the spiders. This is the guy who did the boxes. Etc.” You cannot do that with Olitski. He did too many things to be known for just one. We are stuck, therefore, with only one option-the best option: “Expect nothing. Look at the paintings. Celebrate.”

Painting on the Edge

Born in Snovsk, present-day Ukraine, Olitski emigrated to the United States with his mother as a one-year-old, after his father was murdered by the local Soviet commissar. They settled in Brooklyn, New York, and by high school, Olitski showed an advanced proclivity for art. He won a prize to study art in Manhattan, and eventually earned a scholarship to attend the Pratt Institute. After being drafted into World War II, Olitski used his G.I. Bill privileges to continue his art education in Paris. There, he studied the Modernist masters up close, and faced his own demons. Most notably, he realized that he was being controlled by his own education. An exercise in which he blindfolded himself while painting exemplifies his desire to overcome the manipulation of his own ideas. That same devotion to creative freedom guided him for the rest of life.

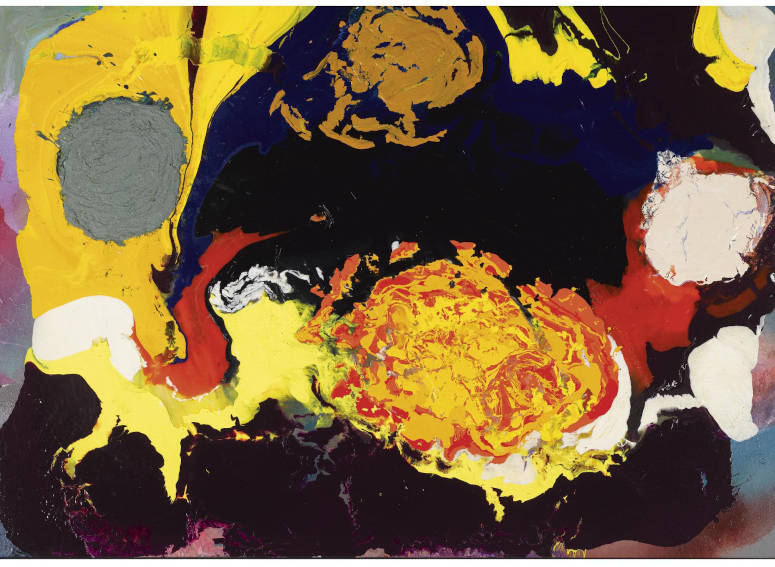

Jules Olitski - With Love and Disregard: Rapture Blessing, 2002. Acrylic on canvas. 60 x 84 in. (152.4 x 213.4 cm). Ameringer Yohe Fine Art, New York. © Jules Olitski

His first painting exhibitions, in the 1950s, were dominated by moody, dark, impastoed abstractions, such as “In Memory of Slain Demikovski” (1958), a work named for his father. By 1960, however, Olitski adopted a completely different approach, using new types of acrylic paints to create flat, vividly colored compositions in which biomorphic, amoeba-like shapes seemingly bloop into existence in pictorial petri dishes. Five years later, he changed directions again, this time using an industrial spray gun in an attempt to achieve his dream of painting “a spray of color that hangs like a cloud, but does not lose its shape.” His spray gun paintings indeed possess many of the same ethereal attributes as gaseous clouds in a distant nebula, backlit by the blasts of exploding stars. This body of work really got Olitski thinking about what he called the “edge” of a picture. “A painting is made from the inside out,” he said. The outer edge of the work, according to his understanding, was not the edge of the canvas, however, but the edge of color. Olitski perceived that color extends beyond the limits of the paint, carried by light and mental perception into the liminal space between the surface of the painting and our eyes.

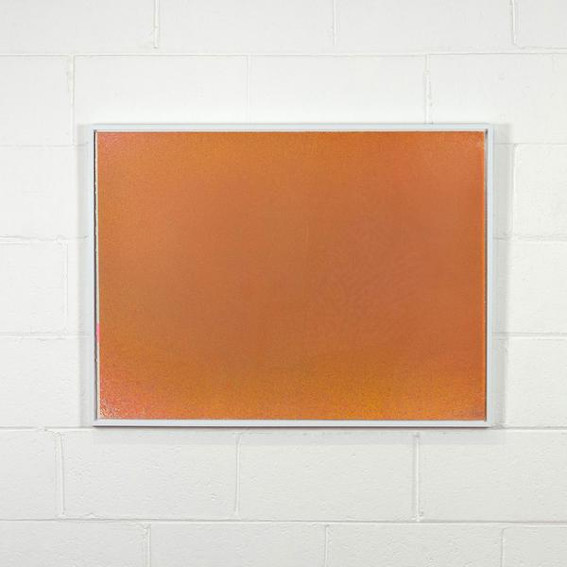

Jules Olitski - Graphic Suite #2 (Orange), 1970. Silkscreen. 35 x 26 in. (work); 36 x 27 in. (framed). © Jules Olitski

Structure and Flow

Around the mid-1970s, Olitski changed methods again, blending his earlier, muted, impasto technique with his use of a spray gun, creating paintings like “Secret Fire – 2” (1977), which project a definite material presence, despite having an ethereal color palette. He continued developing this mixture of methods, creating a body of daring, metallic abstractions in the 1980s, such as “Eternity Domain” (1989), and a body of hellishly primordial works in the 1990s, such as “Upon a Sea” (1996). Though visually diverse, these works do all share a similar guiding principal, which Olitski summed up as follows: “I think of painting as possessed by a structure, but a structure born of the flow of color feeling.” The paintings Olitski created in the final years of his life, such as “With Love and Disregard: Rapture” (2002), express this guiding principal in dramatic fashion. The structure of their material presence is as unyielding as a stone, yet their lightness of being unmistakably claims its chromatic birthright in the “flow of color feeling.”

Jules Olitski - Patutsky Passion, 1963. Magna on canvas. 88 x 71 1/2 in (223.5 x 181.6 cm). Yares Art. © Jules Olitski

In addition to his life-long abstract painting practice, Olitski continually drew figurative portraits and landscapes. He also had a prolific sculpture career, which, like his painting career, was unrestrained by anything but his own imagination. As a child, Olitski received the nickname Prince Patutsky from his stepfather. That name comes up again and again in his work: “Patutsky in Paradise” (1966); “Patutsky Passion” (1963); “Prince Patutsky Command” (1966). It is precisely this devotion to childlike innocence that I see inundating everything Olitski achieved as an artist. Art history normally only bestows legend status on artists who are radical early in their career, followed by “maturity,” and then repetition. Olitski did not fit that character sketch. As experimentally and freely as he could, he just did his work, without expectations, and celebrated. That makes him a legend to me.

Featured image: Jules Olitski - Basium Blush, 1960. Magna on canvas. 79 x 109 in (200.7 x 276.9 cm). Kasmin, New York. © Jules Olitski

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio