Transcending Practices - The Art of Julian Schnabel

Sep 29, 2017

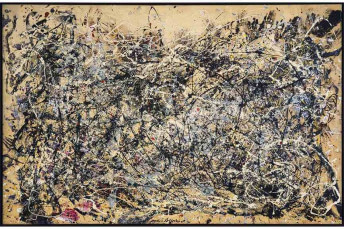

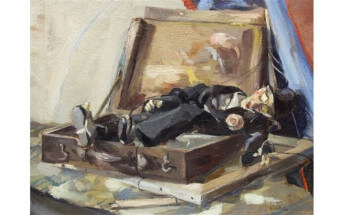

A show of new work by Julian Schnabel opened recently at the Almine Rech Gallery in New York. It contains a couple of bedazzled chairs and an assortment of new paintings. The work is decisively Schnabel-esque. What that means is that some people despise it, some people swoon over it, lots of people dismiss it, and plenty of people want to own it. In the opinion of many people in the professional art world—that quarantined segment of the culture in which creativity and imagination are valued as a serious commodity—Julian Schnabel has long been a hero: the artist who re-legitimized the raw, primal act of painting in an age when hyper-intellectualized, academic villains were desperately trying to destroy it. But to many others in that same world, Schnabel is himself a villain: an egotistical publicity whore with little talent who is only good at one thing: creating a spectacle. No matter what side of that divide you come down on, or whether you are a neutral bystander in the conflict, the fact is that Julian Schnabel is a living legend. And his most recent work does not disappoint. In the lineage of his oeuvre it is right on point: it is raw, aggressive, unabashedly basic, and undeniably fun to look at. And that is the ultimate takeaway. Schnabel is a force for good because he makes stuff that people like to stare at and talk about. He is model for future artists in that he is a living defense of the idea that art is something powerful, which makes it worth doing and worth having. Crucify him if you want. He is still a savior.

From New York to Texas

Julian Schnabel was born in Brooklyn in 1951. His family lived in a vibrant, lively community populated with people from a diverse range of ethnic and religious backgrounds. Schnabel was particularly aware of, and inspired by the intense religious practices of the Catholic and Jewish communities that lived around where he grew up. But at age 13, his family left New York and moved to what could easily be described as its exact opposite: Brownsville, Texas, a border town across the Rio Grande from Matamoros, Mexico.

It was in Brownsville that Schnabel became determined to live the life of an artist. And though he found himself in a far less populated and less urban environment, he nonetheless found similar inspiration from the culture in his new home as he had found back in New York. He was again intrigued by local religious traditions, both those of the Texas natives and the folks living across the border. To him, the aesthetic qualities of Mexican religious art possessed an essential rawness informed by folk traditions and artisan handicraft. And the culture in Brownsville in general was less connected to the high concept intellectual elite, expressing itself far more simply and gracefully through ordinary, straightforward language and customs. Both the aesthetic and the attitude of this place would work its way into the art Schnabel would soon make as an adult.

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Painting Has Not Lived

After earning his BFA from the University of Houston in 1973, Schnabel returned to New York City, where he enrolled as a student in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. At this time he began creating his early figurative paintings, oil on canvas works that were notable for their rejection of the minimal aesthetic of the time. He also started created paintings using unconventional mediums such as was, modeling paste, fiberglass and sheetrock. The subject matter of his work inhabited a sort of formal middle ground between abstraction and figuration, but the titles he gave his paintings, combined with some of the imagery, made it clear that he was creating work that was intended to be read as representational, or even narrative.

His style made him an antagonist to the rising chorus of artists of the previous generation who had declared that painting was dead. Schnabel both cooly and aggressively dismissed such an idea, and by the end of the 1970s proved definitively that in fact, painting had not yet lived. His defining moment came at his first exhibition, in February of 1979, at the Mary Boone Gallery in New York. Among other works on view at the exhibition were his soon-to-be-infamous Plate Paintings: shattered plates attached to wooden surfaces with Bondo then painted over with oils. As with his wax paintings and early oil paintings, the plate paintings were defined by flattened, figurative imagery. They possessed the rugged energy of Art Brut, the emotion and passion of Expressionism, and a sort of arrogant, urban attitude unique to the emerging generation of New York painters that would soon be known as the Neo-Expressionists.

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Attitude Is Not Quite Everything

All of the work for his first gallery show sold out before the opening, immediately establishing Schnabel as an emergent market force. But he nonetheless proclaimed that he was a staunch, dyed-in-the-wool bohemian. As if to prove the point, he frequently appeared in public in his pajamas in the 1980s, looking disheveled and dirty, despite the fact that his company included the likes of Andy Warhol and other major celebrities of the time. To some this was perceived as nothing but an act: an attempt to create a cult of personality that could bolster the value of his aesthetic work. But such a notion is belied by the fact that it was the work itself that was making the biggest impact. Schnabel was making work that challenged what paintings could look like and was doing it in an aesthetically powerful, interesting way. The work was relevant and good. It changed the perception people had of art at the time, which made it important, regardless what the artist wore when he went for coffee, or what he said in the press.

As far as that goes—what he said in the press—Schnabel has gained many enemies through his words. Much derision has been heaped upon him for one particular quote, in which he stated that he was as “close to Picasso” as people were likely to get nowadays. But some of his other quotes are far more revealing about his intentions as an artist. Schnabel has spoken at length, for example, about traveling in Mexico or in Spain and encountering a used drop cloth, or an old tarp, and being drawn to its qualities. He is intrigued by the idea of taking something that has been used before and incorporating that fragmented meaning—that visual memory—into the patchwork of something new. He has said, “After all of these years, I still am trying to find a way of making a mark that has a physical characteristic that alludes to something else,” and has asked “What is it to be alive? That’s the question. And how do you know if you are or you’re not?” Such basic and powerful ideas as allusion and the nature of existence are universally engaged in his work. And quotes such as these reveal the intuitive sincerity and earnestness of someone who is seeking.

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

It Is Not What You Paint

Another well-known quote by Schnabel says basically that it is not what you paint, but how you paint it. And when considering his newest work on view at Amine Rech, that may be the most important notion to keep in mind. Some of the pieces are almost pure appropriation: images taken from other sources and mounted to board, then painted over in what seems to be a quick or even shoddy manner. It would be easy to get angry at works like this. They look like art school sarcasm, or an accident from the back room of a second hand store. But they also possess an undeniable force of attitude and energy. The gesture contained within the marks, the choices of the appropriated images, and the aesthetic presence of the exhibition in its entirety all hint to a vision of the future that is still in its infancy.

If we are to believe that Julian Schnabel was a prophet once, it is not hard to take the leap toward “once a prophet, always a prophet.” There are layers of emotion in these new works that are as raw, as rugged and as aggressive as anything else Schnabel has done in the past five decades. There are also hints that Schnabel has something fresh to share: something analog that is desperately needed right now. Something like what he communicated back in the 1970s: not about painting, per se, but about art in general. Something like, “Art is not dead,” or, “Perhaps art has not yet lived.” Julian Schnabel: Re-Reading is on view through 14 October 2017 at the Almine Rech Gallery, 29 East 78th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, New York.

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

Featured image: Julian Schnabel - Re-Reading, installation view, Almine Rech Gallery, New York, 2017

All images courtesy Almine Rech Gallery, New York

By Phillip Barcio