How Karel Appel Broke the Rules Through an Experiment

We take it for granted today that art is a creative field. But what does that mean? For something to be created, it must not have previously existed. Creativity demands originality. Artists, therefore, are originators. But this was not always the case. In 1921, when Karel Appel was born, creativity was just beginning to assert itself as the driving force of art. Historically speaking, prior to Modernism, success in the art world was achieved more often through things like technical and aesthetic mastery than creativity. Professional artists were expected to mimic the observable world, or at least reference it, and to do it in a way that made intellectual sense. Even abstract artists needed to be able to explain to viewers and critics what they were doing and why they were doing it by referencing ideologies and methodologies that were grounded in existing patterns of thought. Karel Appel was part of the generation of artists that challenged that way of approaching the creation of art. Rather than approaching art from the perspective of what already exists, Appel advocated for an art that expressed what does not yet exist. In doing so, he instituted a new paradigm for artists based on creativity and originality, which not only broke the rules but also perhaps abolished the need for rules altogether.

Indeterminate Experimentation

We are all probably familiar with the aphorism, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” As pithy and cliché as it sounds, that sentiment expresses the feeling that is at the very heart of Modernism. At the end of the 19th Century, anyone in the Western world who had a global perspective and who was capable of critical observation could plainly see, “it was broke:” the “it” being human progress. The logic of Western Civilization had led to an atmosphere of intense competition and violence that threatened to tear the fabric of humanity apart. Though there were admittedly many people at the time benefiting financially or otherwise from the broken system, there were many more who could see that it was time for a change.

Modernism is the name we broadly use to refer to the epoch that began near the end of the 19th Century, during which a series of broad transformative efforts were made by people to re-imagine what modern human society is and could be. The fundamental tenet of Modernism was best expressed by the author Ezra Pound, when he said, “Make it new!” He was talking about the widely held desire so many people had to bring into existence some kind of alternative cultural reality. But the question on every Modernist’s mind was, “How do we make it new?” Most of the various answers that were proposed involved inventing new artistic styles, or abstracting the current way of viewing the world, or innovating the use of aesthetic elements such as color, line or form. The solution Karel Appel proposed was unique. It ignored aesthetics and style entirely, and focused on one simple factor: originality, enabled by unfettered freedom to experiment.

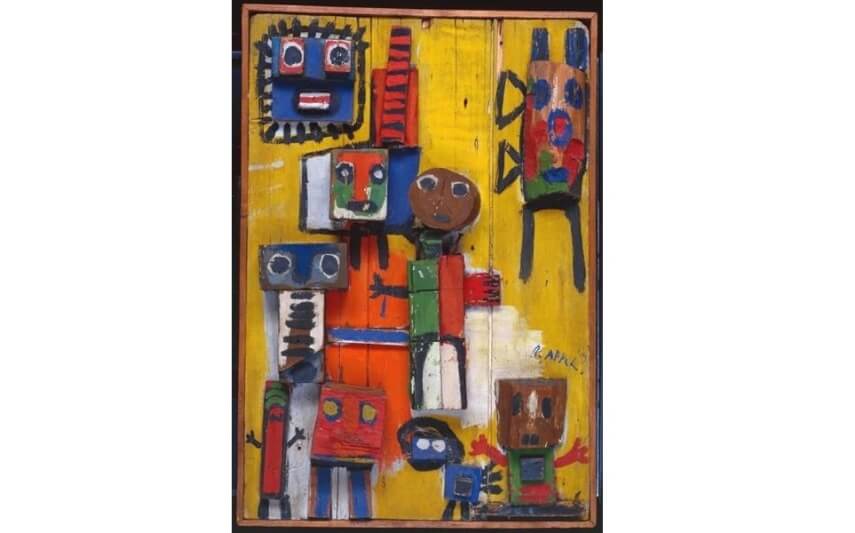

Karel Appel - The Wild Firemen, 1947. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

The Presence of Absence

For Appel, the value of the artistic act had nothing to do with the product that would eventually be created as a result of the act. The important thing was the creative process. The point was not for an artist to talk about what was going to be made, or to judge or explain what eventually was made. The point was simply to create: to allow something unknown to manifest, allowing the unreal to become real. As Appel put it, “If the stroke of the brush is so important, it is because it expresses precisely what is not there.”

Karel Appel - Untitled Sculpture, 1950. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

It has been often noted that Appel’s earliest efforts in unfettered experimental aesthetic creation resemble pictures made by children. Their quasi-figurative, quasi-abstract compositions utilize a seemingly chaotic vocabulary of color and primal expressions of line and form. They were originally so misunderstood, in fact, that when they were first exhibited in the late 1940s they were publicly mocked. But Appel was undeterred. He was not motivated by public approval. He was dedicated to confronting absence through a process of manifesting presence. He was on a journey toward originality, without regard to where that journey ended up or what it looked like.

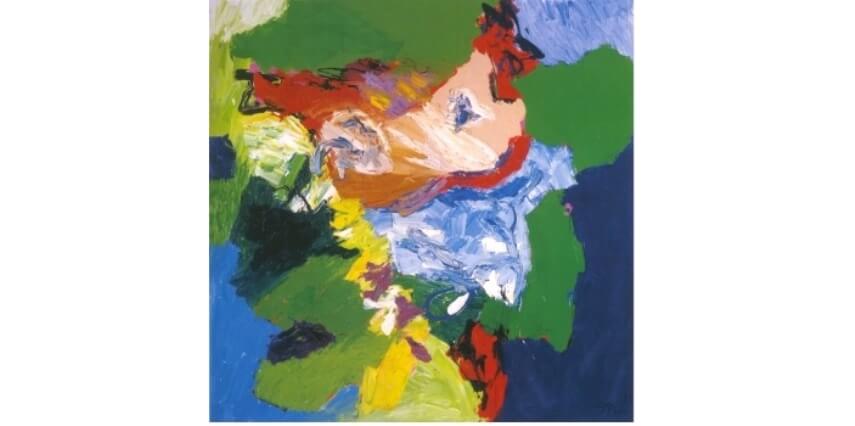

Karel Appel - Mindscape #12, 1977. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

Karel Appel and the CoBrA Group

What was it that was so shocking about Appel’s paintings? Was it the fact that he seemed not to care about the aesthetic results of his process? Or was it the freedom with which he created that was so disturbing? The answer may be found in the circumstances of the world into which Appel’s art was introduced. His first exhibition occurred in 1946, as Europe had just emerged from World War II. The widely held belief was that the world had gone mad. The practicalities of rebuilding the continent and of confronting the staggering losses forced a stark sense of existential angst on the culture. There was a powerful metaphysical desire to contextualize the war in order for the survivors to feel the sacrifice had been worth the cost.

During the war, the inhabitants of Denmark, the Netherlands and Belgium were effectively completely cut off from the rest of the world by the German occupation of their territory. Immediately after the war, it became apparent that a small group of artists that had spent the war in Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam had arrived at a similar approach to art making. The group, which included Appel, rejected the logic and rationale of existing Western institutions. They were inspired by primitive folk art and the artwork of children. They made art rooted in intuition, spontaneity and freedom of expression. When these artists began to exhibit together, they were called the CoBrA group, a label taken from the first letters of their native cities.

Karel Appel - Questioning Children, 1949. Gouache on wood. Object: 873 x 598 x 158 mm, frame: 1084 x 818 x 220 mm. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

A Convergence of Influences

Appel did not arrive at his approach in a vacuum. He mentions in his writing seeing a Kurt Schwitters exhibition, his first experience witnessing what he calls an objet trouvé, an artwork made from found objects. He calls the experience “shattering.” It released him from the need to follow historic traditions regarding mediums, and for that matter freed him from all historical traditions whatsoever. The intuitive, childlike freedom with which Appel creates also owes a debt to artists like Paul Klee and Joan Miro, both of whom conveyed a spirit of uninhibited freedom in their work.

Aside from artistic influences, Appel also writes about three other influences on his thinking. He mentions the book Leaves of Grass by the American poet Walt Whitman, the long-form poem The Songs of Maldoror by the Uruguayan-French writer Comte de Lautréamont, and the writings of Jiddu Krishnamurti, an influential thinker on the nature of humankind. Taken together these influences display a wide range or thinking. Leaves of Grass is one of the most eloquent and optimistic celebrations of freedom and openness ever written. The Songs of Madoror, however, is one of the most distinctive explorations of total evil ever composed. Meanwhile, Jiddu Krishnamurti encouraged dedication only to personal consciousness in order to experience truth and become free.

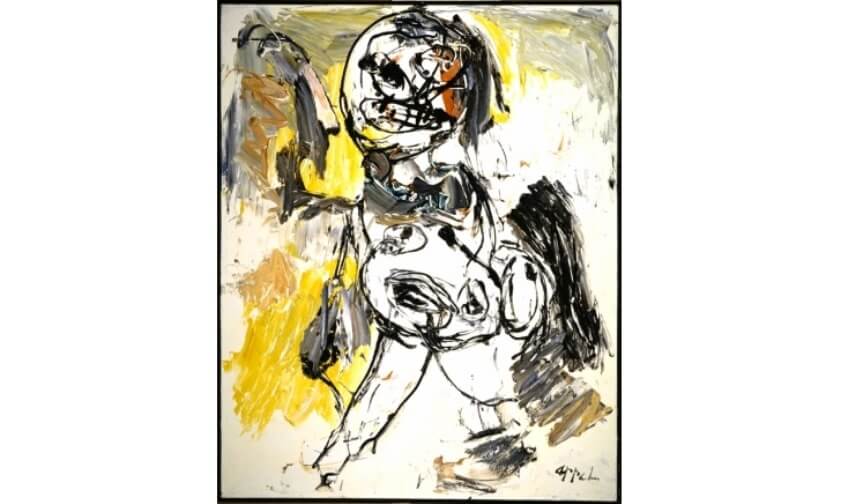

Karel Appel - from Nude series, 1963. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

Appel’s Legacy

By observing the unrestricted enthusiasm of children and folk artists, Appel found a pathway to discovering within himself that same sense of freedom. He put a premium on the value of a free human mind. He demonstrated in a practical sense how artists could freely and spontaneously express the inner experience of their own truth. That act alone inspired an entire generation of artists, including such important figures as Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, who went on to change the world through movements such as Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism.

But beyond the individual artists and styles he influenced, the true legacy of Appel’s contribution can be summed up in the words “creative process.” It is entirely thanks to artists like Appel that we take for granted today that the most important aspect of art should be originality, and not mimicry. In 1989, Appel summed up his experience, saying, “Creativity is very fragile. It's like a leaf in the fall; it hangs and when it drops you don't know where it's drifting…As an artist you have to fight and survive the wilderness to keep your creative freedom.” By embracing true originality, Appel eliminated the need for adherence to any path other than the free expression. Through his work we learn that the important thing isn’t just to collect, categorize and admire the products of an artist’s labor, but to marvel at the originality and freedom from which these objects came, and to embrace their source as the truly precious and unending process of creativity.

Featured Image: Karel Appel - Little Moon Men, 1946. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Karel Appel Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio