Cutting the Canvas - The Story of Lucio Fontana

Abstract art creates questions, not answers. Thus it invites attack. Not everyone likes questions. People often desire from art only comfort and beauty. But many abstract artists are not decorator-consolers so much as philosopher-scientists: people seeking to experience and interpret the universe, not just dress it up. Lucio Fontana was one such artist. As the founder of a revolutionary technique called Spazialismo, or Spatialism, Fontana was deeply concerned with the practical ways of making art that confronted the mysterious properties of space. He was curious how forms inhabited space, how they could contain space, and how by eliminating mass space could be created. He was particularly fascinated by how a hole in a form could create a void through which the experience of space could be expanded. But Spazialismo was not only limited to such academic questions. As Fontana said in 1967, in reference to the fact that humans were then routinely traveling into outer space on rockets, “Now in space there is no longer any measurement. Now you see infinity…here is the void, man is reduced to nothing…And my art too is all based on this purity, on this philosophy of nothing, which is not a destructive nothing, but a creative nothing.”

Lucio Fontana and Multi-Disciplinary Art

It is a historical glitch that Lucio Fontana is mostly referred to as a painter. He was trained as a sculptor. He was born in Argentina in 1899 to a father who sculpted and who first taught Lucio the basics of his craft. After decades of working alongside his father, Lucio moved to Milan in 1927 and enrolled as a sculpture student at the Brera Academy. He had his first sculptural show at the age of 31 in a Milan gallery. Referring to himself as an abstract sculptor, he joined the artist association Abstraction-Création in 1935, and in the 1940s he returned to Argentina where he taught sculpture and continued to make three-dimensional works.

In truth, Fontana worked almost exclusively in the medium of sculpture until 1948. And even then when he did start making objects resembling paintings, he insisted they were not paintings but rather “a new thing in sculpture.” But even so, if we were to be true to Fontana’s full intentions as an artist we would not call him a sculptor either. We would simply call him an artist, and maybe an explorer of space.

Lucio Fontana - Figura allo specchio. Ceramic. 24,5 x 15 x 13 cm. © Lucio Fontana

The White Manifesto

In 1946, Fontana had come to the decision that the definitions of sculpture and painting were no longer sufficient to accommodate the theoretical nature of his work. He led a group of artists and students in the creation of what he called the White Manifesto, the first of several documents Fontana would help write that he hoped would address the need for a new approach to art. The White Manifesto brought attention to the need for art to be in line with other intellectual pursuits of the day. It pointed out that recent scientific and philosophical developments were focused on the idea of synthesis, that different ideas should be combined to form a unified point of view.

Fontana advocated a similar “synthetic” approach to the creation of art, one that would synthesize what he called the “traditional ‘static’ art forms” in order to create a complete method of aesthetic expression that would “involve the dynamic principle of movement through time and space.” With the ideas expressed in the White Manifesto, Fontana essentially invented multi-disciplinary art: the perspective that an artist should be able to work in any and all mediums, using whatever method best suits a particular idea.

Lucio Fontana - Spatial Environment, illuminated. © Lucio Fontana

Adventures in Space

Earlier in his career, Fontana had been criticized for painting his abstract sculptural forms in loud, seemingly random colors. He responded that he was attempting to use color to engage the works with their surroundings, to bridge the space between object and viewer. He continued to address this concern throughout his career. He wanted space itself to manifest as form and become the subject of his art. But he could not ascertain how that might be accomplished. As he wrote once in his journal, “no form is spatial.”

Lucio Fontana - Spatial Concept, 1949. © Lucio Fontana

But in 1949, Fontana experienced breakthroughs that led him closer to his goal. The first manifested as a work called Spatial Environment. For this groundbreaking effort, Fontana darkened a room in which the walls were painted black and hung from the ceiling abstract papier-mâché forms painted in neon colors that glowed when hit with ultraviolet light. He transformed the exhibition space into part of the work of art, creating a work that predated installation art and the Light and Space Movement by more than a decade, yet embodied many of their concepts. But the subject of the work was still not space, since the focus on the viewer experience was on the glowing sculptural forms.

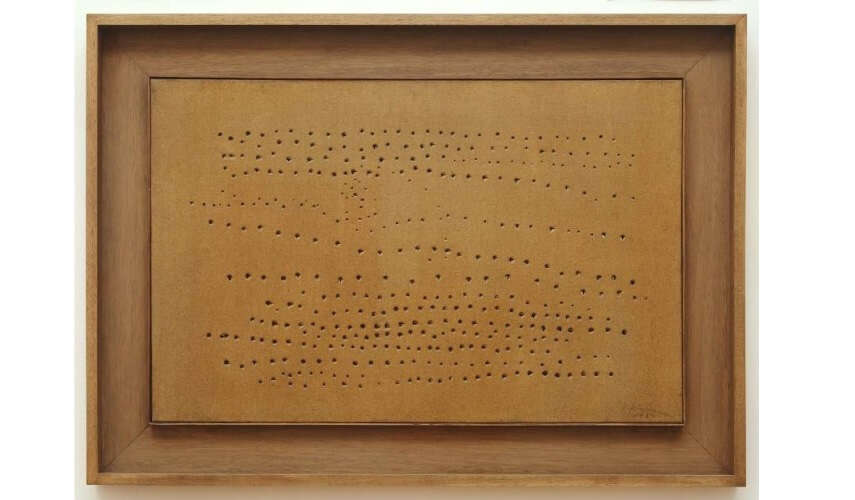

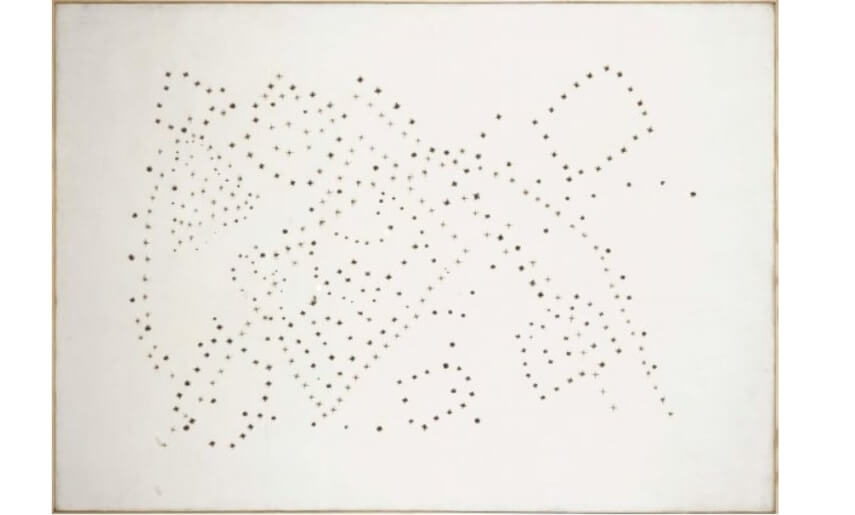

Lucio Fontana - Spatial Concept, 1950. Acrylic on canvas. 69,5 x 99,5 cm. © Lucio Fontana

Spatial Concepts

Fontana’s next breakthrough took his work in the entirely opposite direction. Rather than transforming an entire room into empty space then filling it with an object, he decided to take an object and use it as an entry point into space. He stretched canvas onto stretcher bars as if to make a traditional painting then poked holes through the canvas with a knife before applying a monochromatic layer of paint.

Lucio Fontana - Concetto spaziale (56 P 8), 1956, with glass beads and stones added. © Lucio Fontana

Although technically a painting, the holes acted as voids in the form offering access to the space behind the canvas. This simple gesture transformed the painting into a sculpture. But although this in itself was revolutionary, and demonstrative of his ideas about multi-disciplinary art, he still felt it did not create form out of space. So Fontana experimented with different expressions of the general thought. He poked holes in such a way that it created circles, triangles and other forms on the surface. He also added stones, glass and crystals to some canvases, extending the surface outward in space while also opening up the space beyond.

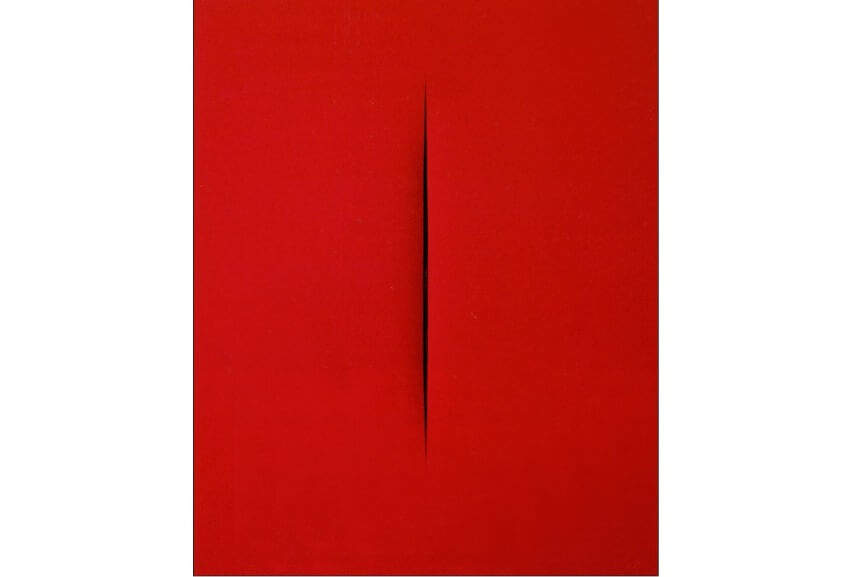

Lucio Fontana - Concetto spaziale – Attesa, 1965. © Lucio Fontana

A Single Slash

In the 1950s, Fontana had a revelation. He began slicing his canvases, works he called Tagli, or cuts. He gradually evolved this idea until in 1959 he arrived at what he considered the ultimate manifestation of the expression: a single slash through an otherwise monochromatic canvas. It was with this gesture that he accomplished his goal of creating form out of space, saying in 1968, “My discovery was the hole and that's it. I am happy to go to the grave after such a discovery.”

Fontana gave all of his cut-up objects the same name: Concetto Spaziale, or Space Concept. When he finally discovered the simplicity and elegance of the long slashes he gave those paintings the additional subtitle of attesa. In Italian, attesa means waiting, or hopeful expectation. As is clear, Fontana was not only interested in how people perceived and conceived of space. He was interested in how people perceived and conceived of themselves. Through the use of a void he not only manifested form out of space, he also manifested something else, something both abstract and concrete: the hopeful expectations of what lies beyond a work of art.

Featured Image: Lucio Fontana - Corrida, 1948. Painted ceramic. © Lucio Fontana

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio