How Drawing Revitalized Post-War America - at MoMA

May 12, 2021

With COVID restrictions in New York lifting, several museum shows whose runs were extended during the pandemic shutdown are beckoning. Among the best for fans of abstraction is Degree Zero: Drawing at Midcentury at MoMA, an exhibition of 79 mostly abstract drawings created between 1950 and 1961. What makes this exhibition extraordinary is two questions the curation raises, about the nature and value of drawing as an artistic medium, and about the power of institutions to construct, and re-construct, official versions of art history. In terms of the value of drawing as a medium, the stakes generally feel lower than with its dizygotic twins, paintings and sculpture. Paper, pens and pencils are inexpensive and easy to get compared to good paints, canvas, metal, clay or stone. Artists themselves often consider drawings to be practice for other works. Ironically, such low expectations sometimes result in masterpieces by lending drawing a sense of freedom that more planned and deliberate mediums resist. Degree Zero examines this phenomenon in two ways. First, the curation centers dozens of drawings that were clearly intended as finished—not preparatory—works, such as a breathtaking, yello, untitled drawing by Swiss artist Sonja Sekula, or the perfect “Composition with One Flag” by Italian-Brazillian artist Alfredo Volpi. Second, it includes several supposedly preparatory works—most notably the Ellsworth Kelly drawings “Study for La Combe II” (1950) and “Study for Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris” (1949)—which are in many ways superior to the final versions they preceded. As for what Degree Zero does to address the power of institutions like MoMA to write and re-write art history, the entire exhibition is basically an attempt to correct the narrow narrative MoMA contributed to in the first place, that Post War art was largely an American, white, male affair, dominated by Abstract Expressionism. Pulled entirely from the permanent MoMA collection, Degree Zero includes artists of two genders from five continents, represents multiple racial backgrounds, and includes some untrained artists. That does nothing to erase old sins, but it at least testifies to the desire MoMA has today to start fixing a broken past.

Drawers of Drawings

Perhaps the most notable thing about Degree Zero is the fact that the exhibition exists at all. Any professional drawer will tell you that the reason drawings tend to command lower prices than paintings on both the primary and secondary market is that collectors tend not to see drawings as archival. Many drawers in fact neither invest the time to choose quality paper, prepare the surface, select quality mediums, nor protect the work when it is finished. When you do buy a drawing, you end up having to spend a lot of money framing the work, taking care to choose the correct type of glass, and hanging it in a place where it will not be damaged by atmospheric conditions. Even when properly made and protected, drawings tend to degrade more rapidly than paintings. This is why a lot of drawings in museum collections just end up in flat file drawers for decades, ignored and eventually forgotten about. When they are re-discovered, they are sometimes beyond saving.

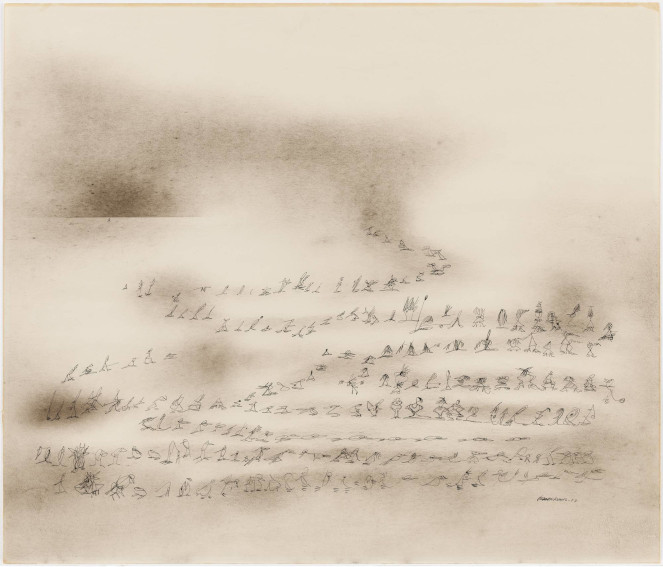

Norman Lewis - The Messenger, 1952. Charcoal and ink on paper. 26 x 30 3/8′′ (66.1 x 77.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller © Estate of Norman Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Somehow, MoMA not only managed to collect 79 drawings from a single decade, but now that they are more than 60 years old, a great number of these drawings are still in extraordinarily good condition. One fantastic example is “Untiled (Smoke Drawing)” (1959), by Otto Piene. The artist made this work by suspending a sheet of paper on a metal screen over a burning flame, allowing the smoke to scorch a circular pattern on the paper. Somehow, this charred sheet of paper remains completely intact, and sublimely expressive, 62 years later. Another remarkable example is “The Messenger” (1952), a charcoal and ink drawing on paper by Norman Lewis. This work retains such detail, delicacy and nuance that nearly 70 years after its creation it seems to still contain the echo of the genteel, thoughtful, living heart of this extraordinary artist. The wonderful preservation of these works de-contextualizes the medium not as something doomed to deteriorate, but as something uniquely expressive of the mind and body of the drawer who made it that is worth protecting and collecting.

Installation view of Degree Zero: Drawing at Midcentury, November 1, 2020–February 6, 2021 at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Robert Gerhardt

Righting History

Samantha Friedman, associate MoMA curator of drawings and prints, deserves additional credit for how well she selected works that convey a global, multi-gendered, multi-racial, multi-didactic perspective. Yet, I am also equally impressed by the effect Degree Zero has had on my understanding on the individual oeuvres of some of the artists in the show. A pair of Louise Bourgeois drawings absolutely captivated me, reiterating the child that lives within adults, and offering a delightful glimpse of the youthful soul of this artist whose sculptures I find terrifyingly and profoundly adult. “Untitled (Florence)” (1952) by Jay DeFeo is the only small scale by this artist I have ever seen. Its shocking clarity and passion imprinted the image on my mind, likely permanently. An untitled, black and white drawing by Georges Mathieu from 1958 set the bar for respect for this painter even higher. I had always been a fan of his singularly cosmic abstractions, but seeing what he did here without the aid of color and texture proved to me his mastery.

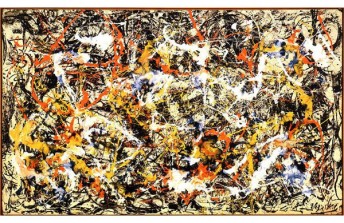

Joan Mitchell - Untitled, 1957. Oil on paper. 19 1/2 x 17 1/2′′ (49.5 x 44.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Drawings Funds © Estate of Joan Mitchell

The final way I feel that Degree Zero “rights” history is in its willingness to reach outside of what would normally be considered a drawing. New City (1953), a watercolor and ink on paper by Dorothy Dehner, would normally be considered simply a watercolor painting, but its linear countenance surely suggests it belongs in this show. Similarly, a colorful, untitled work in pastels by Beauford Delaney would normally be shown as a painting, or just a work on paper. The same could be said for the stunning untitled oil on paper by Joan Mitchel from 1957; a thrown-ball acrylic on paper work by Saburo Murakami; and ink rubbing by Sari Dienes; and and the collage “2Letters Ms” (1961) by Vera Molnar. Categorizing these works as drawings blurs definitions in a subtle, subversive way, and adds to the overall effect this exhibition achieves of expanding the experience of drawing, and art history, to be more open than it has been in the past.

Featured image: Otto Piene - Untitled (Smoke Drawing), 1959. Soot on paper. 20 x 29′′ (51 x 73 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchased with funds provided by Sheldon H. Solow © 2019 Otto Piene / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG. Bild-Kunst, Germany

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio