Neo-Dada and Abstraction in the Game of Meaning

As its name might suggest, Neo-Dada should not be confused with Dada. Although some artists associated with both movements used similar techniques, and the meaning of the works associated with both movements are similarly unclear, there was one defining difference between the two. Simply put, Dada was anti-art. Neo-Dada was anti-Dada. The Dadaists saw society as meaningless, and the art world as a useless relic of its absurd, suicidal, bourgeois logic. The Neo-Dadaists believed in meaning, especially in art, but felt that it was something personal that could only be defined by an individual. And they embraced the fine art world, working within it to expand the definition of what fine art could be.

A Neo-Dada State of Mind

At the heart of the Neo-Dada movement was meaning. For most of the 1940s, the Abstract Expressionists had been at the forefront of the American art scene. Their work was inherently personal, being derived from the subconscious of the painters that made it. While viewers might hope to connect with the vibe of an Abstract Expressionist work, they could never fully understand the work’s meaning since it originated in the inner sanctum of the artist’s primal mind.

The Neo-Dadaists believed that the intent of the artist was irrelevant, and that the meaning of a work of art could only fully be communicated through a viewer’s interpretation. Within this game of determining what exactly meaning is and from whence it originally comes, abstraction was the Neo-Dadaist painter’s best friend.

Robert Rauschenberg - Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame, 64.14 x 55.25 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Neo-Dada and Abstraction

The first and most famous Neo-Dada abstract painter was Robert Rauschenberg . His first Neo-Dada paintings weren’t hung in a gallery, however; they were part of a play. One of the odd circumstances that Dada and Neo-Dada have in common is that each movement was instigated by a work of theater. The play Ubu Roi, first performed in 1886, is considered to be the first Dadaist work. Known for its mockery of absurd social conventions, it laid the groundwork for the anti-art movement to come. The first Neo-Dada work was John Cage’s Theater Piece No. 1, performed in 1952. It consisted of simultaneous presentations of dances, poems, slide projections, a film, and four paintings by Rauschenberg.

Present in Theater Piece No. 1 were all four of Neo-Dada’s main concepts: 1) random chance (as the performances were unscripted); 2) unrevealed artist’s intent (other than to be unclear); 3) contradictory forces (with simultaneous contrary demands being made on the audience); and 4) the viewers were responsible for assigning meaning to the work. The Rauschenberg paintings included in Theater Piece No. 1 were four of his White Paintings, which were blank canvases painted with white oil paint, hung from the ceiling in the shape of a cross.

Rauschenberg’s White Paintings express all four notions dear to Neo-Dada. Their pure white surfaces reflect subtle elements of the surroundings, which change according to the random chance of who is viewing them. They reveal nothing about the artist’s intent. They are awaiting content and yet nonetheless hung as finished art, the ultimate contradiction. And as blank surfaces they are entirely open to the viewer’s interpretation.

In 1953, Rauschenberg took Neo-Dada abstraction a step further, attaching to it an expression of the movement’s cultural agenda. Rauschenerg started with a work of art by Willem De Kooning, one of the most famous of the Abstract Expressionists, and then erased the marks that de Kooning made, resulting in an essentially blank surface. This work expressed many of the same notions as his White Paintings, further adding a direct challenge to the relevance of Abstract Expressionist ideals.

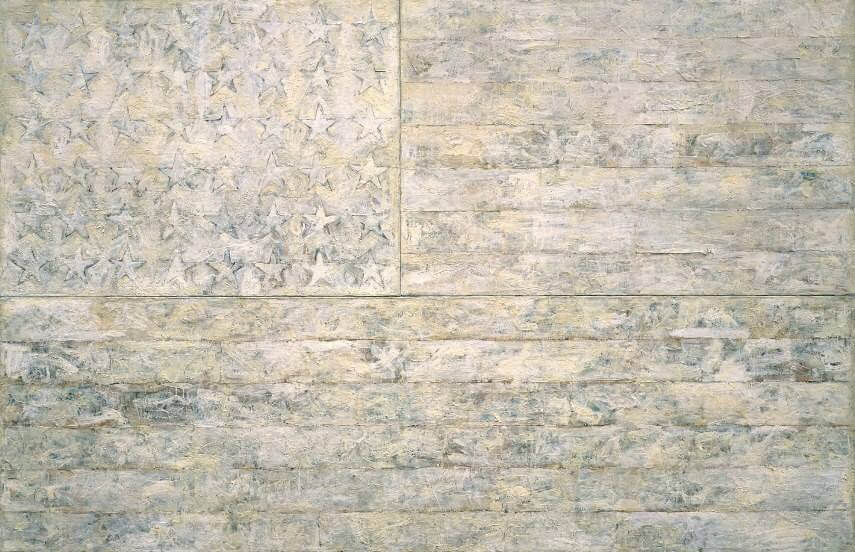

Jasper Johns - White Flag, 1955, Encaustic, oil, newsprint, and charcoal on canvas, 198.9 x 306.7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, © Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns and the Expansion of Abstraction

Obviously an abstract painting is inherently wide open for viewer interpretation. But one Neo-Dada painter took the idea of abstraction to a new level. Jasper Johns created collages out of media images using the technique to make images based on a visual language composed of familiar things such as flags, targets, numbers, letters and other images from the popular culture. He called his subjects for these paintings “things the mind already knows.” In the same way that geometric abstract painters had taken squares, circles and lines and used them to compose an abstract image, Jasper Johns took the elemental pieces of media culture and composed an image appropriated from the recognizable cultural aesthetic.

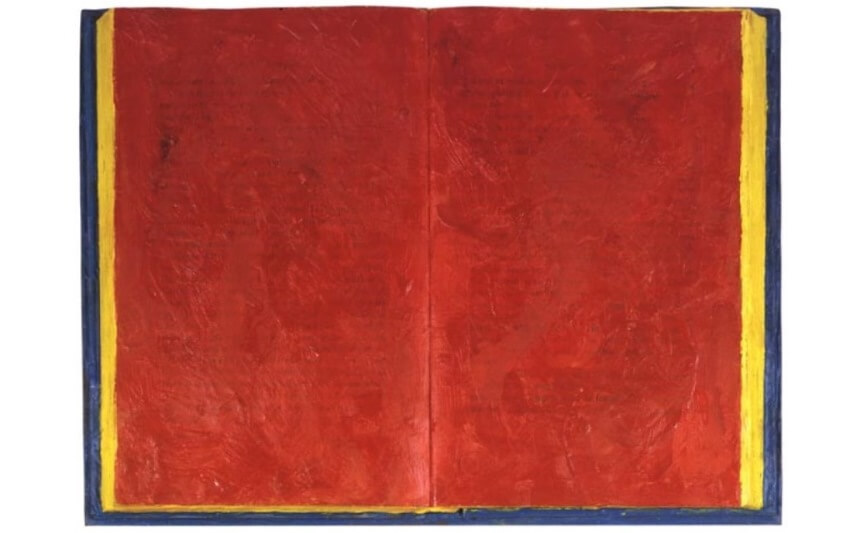

Jasper Johns - Book, 1957, Encaustic and book on wood, 24.8 x 33 cm, © Jasper Johns

By taking these familiar images and abstracting them, and building the compositions out of collaged bits of unreadable fragments of detritus, he challenged the notions of what any of the individual elements of the image meant. Rather than seeming absurd, Johns’ images invited profound layers of interpretation. They elevated symbolic cultural imagery to fine art and re-framed the politically volatile technique of collage, making it friendly to the art world once again.

Rauschenberg saw abstract Neo-Dadaism as a way to give the interpretive power in the art world back to the viewers, democratizing it in a way that paved the way for movements such as Minimalism. Rather than having to wonder what the mystical Abstract Expressionists were trying to say, his white paintings told viewers that it was actually they alone who could successfully finish a work of art through the act of personal interpretation.

By abstracting things such as American flags or maps or letters of the alphabet, Johns suggested that the aesthetic language of media and culture was inherently as meaningless as geometric shapes. A painting of an American Flag shape without the American flag colors, for example, is not an American flag at all. Its abstracted version invites the viewer to contemplate what possible meanings it might have beyond its association with nationality, history, culture, people and geography. Johns’ use of familiar cultural imagery took power away from the media, handing it back to ordinary citizens and paving the way for Pop Art.

Featured Image: Robert Rauschenberg - White Painting (seven panels), 1951, Oil on canvas, 182.9 x 320 cm, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio