Optical Illusion Art That Marked the 20th Century

Reality is not always fixed; or at least it can seem that way to the human mind. What we believe is based to some degree on what we perceive, but what we perceive is also sometimes determined by what we believe. Optical illusion art, or Op Art for short, is an aesthetic style that intentionally exploits that oddity of human perception that gives the human eye the ability to deceive the human brain. By manipulating patterns, shapes, colors, materials and forms, Op Artists strive to create phenomena that fool the eye, confusing viewers into seeing more than what is actually there. And since belief can be as influential as fact, Op Art asks the question of what matters more: perception or truth.

A Brief History of Optical Illusion Art

Op Art has its roots in a technique called trompe-l'œil,which is French for trick the eye. The earliest references to such tendencies in art date back to antiquity, when ancient Greek artists attempted to make paintings so realistic that people would literally be fooled into believing their images were real. The technique has subsequently gone in and out of fashion numerous times throughout the centuries, hitting its stride in the 19th Century with trompe-l'œil paintings like Escaping Criticism, painted in 1874 by Pere Borrell del Caso, which shows a hyper-realistic image of a child climbing out of a picture frame.

Pere Borrell del Caso - Escaping Criticism, 1874. Oil on canvas. Collection Banco de España, Madrid, © Pere Borrell del Caso

Pere Borrell del Caso - Escaping Criticism, 1874. Oil on canvas. Collection Banco de España, Madrid, © Pere Borrell del Caso

But although also intended to fool the eye, Op Art is not the same as hyper-realistic art. In fact, Op Art as we know it today is more often abstract, relying on geometric compositions to convince the eye that unreal forms and spatial planes exist. The first abstract technique that was designed to trick the eye was called Pointillism. Rather than mixing colors ahead of time, pointillist painters placed unmixed colors beside each other on a canvas, creating the illusion of solid fields of colors. When these paintings are viewed from a distance it seems that the colors are mixed. Georges Seurat invented Pointillism and mastered the effect with paintings such as Lighthouse at Honfleur.

Georges Seurat - Lighthouse at Honfleur, 1886. Oil on canvas. Overall: 66.7 x 81.9 cm (26 1/4 x 32 1/4 in.), framed: 94.6 x 109.4 x 10.3 cm (37 1/4 x 43 1/16 x 4 1/16 in.). Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Georges Seurat - Lighthouse at Honfleur, 1886. Oil on canvas. Overall: 66.7 x 81.9 cm (26 1/4 x 32 1/4 in.), framed: 94.6 x 109.4 x 10.3 cm (37 1/4 x 43 1/16 x 4 1/16 in.). Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Abstract Illusions

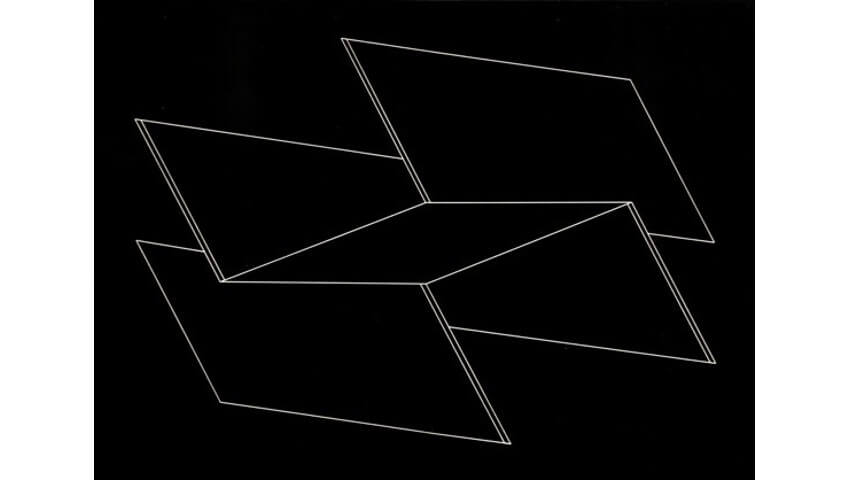

The concept underlying Pointillism ultimately gave rise to many other techniques as artists searched for ways to deceive the mind into completing a picture. It inspired the Divisionism of the Italian Futurists, and the four-dimensional planes of Cubism. But its most successful application came when it was combined with the aesthetics of geometric abstraction, such as with the abstract geometric etching Structural Constellation, painted in 1913 by Josef Albers.

According to his own statements, Albers was not trying to make an optical illusion with this work. He was engaged in simple compositional experiments regarding the perception of line and forms on a two-dimensional surface. Nonetheless, he discovered that the arrangement of lines, forms and colors on a surface can indeed alter the way the mind perceives what is real. And although he did not intentionally try to fool viewers with his works, he nonetheless spent a lifetime investigating these effects.

Josef Albers - Structural Constellation, 1913. White lines etched in black background on wood. © 2019 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Josef Albers - Structural Constellation, 1913. White lines etched in black background on wood. © 2019 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Zebras and Chess Boards

Victor Vasarely, a contemporary of Albers, did, however, engage in a conscious effort to find ways to deceive viewers with his art. Vasarely was as much a scientist as he was a painter, and he was particularly interested in the ways these two pursuits came together to affect perception. As early as the 1920s, the artist had learned that through the manipulation of line alone he could completely distort a two-dimensional surface in a way that deceived the mind into perceiving it as three-dimensional space.

One subject Vasarely turned to repeatedly in his work was the zebra. The stripes of this animal actually serve to deceive natural predators who cannot tell which direction the animal is running because of the interplay of its black and white stripes with their surroundings. As he unlocked the secrets of this phenomenon, he applied them to more complex geometric compositions, and by the 1960s created a signature style that inspired what is today considered to be the Modernist Op Art movement.

Victor Vasarely - Zebra, 1938. © Victor Vasarely

Victor Vasarely - Zebra, 1938. © Victor Vasarely

Black and White

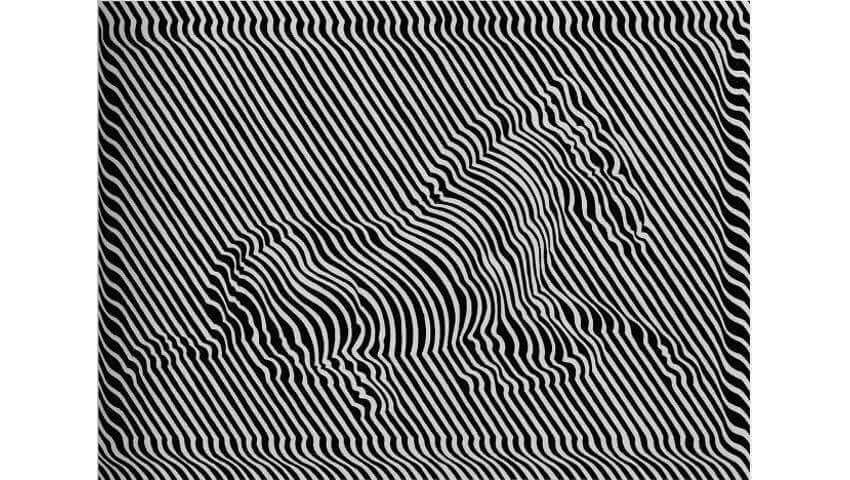

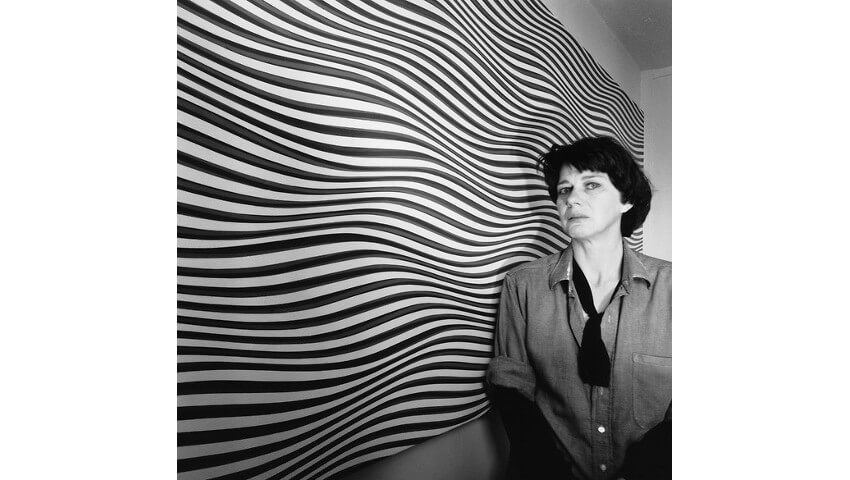

One of the most famous Optical Illusion Artists of the 20th Century was the British artist Bridget Riley, who was directly inspired by the work of Victor Vasarely. Riley studied at the Royal College of Art in the early 1950s. Her early work was figurative, but after taking a job as an illustrator at an advertising firm she became more interested in creating visual illusions. She began investigating Pointillism and then Divisionism and then finally developed her own signature style of Op Art, based primarily on black and white geometric abstraction.

Riley was so successful in creating optical illusions in her work that viewers sometimes reported experiencing feelings of sea sickness or motion sickness when looking at her paintings. This phenomenon fascinated Riley, who became convinced that the line between perception and reality is indeed quite fragile, and that a belief caused by an illusion could actually manifest real consequences in the physical world. Said Riley, “There was a time when meanings were focused and reality could be fixed; when that sort of belief disappeared, things became uncertain and open to interpretation.”

Bridget Riley in front of one of her large-scale, hypnotic Op Art paintings, © Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley in front of one of her large-scale, hypnotic Op Art paintings, © Bridget Riley

The Responsive Eye

The height of the Modernist Op Art movement came with an exhibition called The Responsive Eye that toured the United States in 1965. This exhibition featured more than 120 artworks by dozens of artists representing a wide range of aesthetic positions. The show included the highly illusionist works of Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley as well as more subdued geometric abstractionists from artists like Frank Stella and Alexander Liberman and kinetic sculptures from artists like Wen-Ying Tsai and Carlos Cruz-Diez.

Also included in The Responsive Eye group was the sculptor Jesús Rafael Soto, who arguably took Op Art the farthest into the realm of three-dimensional perception with a body of work called Penetrables. These interactive creations consist of hundred of partially painted, dangling plastic tubes that viewers can walk through. When undisturbed they present a striking illusion that a concrete form is hovering in space. But when spectators physically interact with the sculptures the illusion dissolves, giving the perception that a concrete reality can, in fact, be warped and altered by the human touch.

Jesús Rafael Soto - Penetrable. © Jesús Rafael Soto

Jesús Rafael Soto - Penetrable. © Jesús Rafael Soto

The Op Art Legacy

The blessing and the curse of Op Art is its popularity. When the movement was at its height in the 1960s, many critics despised it because its imagery was appropriated ravenously by makers of kitsch items like t-shirts, coffee mugs and posters. But to artists like Victor Vasarely and Jesús Rafael Soto, that was precisely the point.

These creatives believed that the value of a work of art is determined by the degree to which a viewer may participate in its completion. They made aesthetic phenomena that adapts to each new viewer, creating unlimited interpretive possibilities. The fact that their art was consumed on a mass level was perfectly in line with their concept, which is that there should be no barrier between people and art, and that whatever barriers seem to exist only exist in our perception.

Featured image: Victor Vasarely - Vega-Nor, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 200 x 200 cm. © Victor Vasarely

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio