Discover the Mysteries of Orphism in Painting

In the field of abstract art, mysticism and science sometimes become unwitting bedfellows. One example is Orphism, a brief and sometimes misunderstood art movement from the early years of the 20th Century. Orphism’s artistic roots are in Cubism, Fauvism and Divisionism. Its mystical roots are hinted at by its name, derived from the mythic musician and poet Orpheus, whose music is said to have been able to charm the devil and move even stones to dance. Orphism’s scientific credentials hark back to the writings of Michel Eugène Chevreul whose name is engraved on the Eiffel Tower, and who was perhaps the least mystical, most skeptical French scientist ever. Somehow in the confluence of all these influences Orphism was born, and went on to influence generations of abstract artists to come.

The Birth of Orphism

Orphism describes the practice of a small group of mostly-European painters who were painting bright, colorful abstract paintings in a quasi-Cubist style roughly between 1912 and 1916 (although the founders continued working in the style for many more decades). The movement was named by Guillaume Apollinaire, the French art critic who also coined Cubism and Surrealism. Apollinaire noticed that a small number of painters were developing a unique practice-based partially on Cubist theories, but with a focus on vivid contrasting colors and increasingly abstract content.

Apollinaire called these painters Orphists in reference to the idealized reputation Orpheus enjoys as the ultimate artist. The word was intended as a contrast to the hyper-pragmatic Analytic Cubism. Apollinaire noted how Orphists utilized color, line and form in the same way musicians use notes, to create abstract compositions that could inspire emotion.

But despite Apollinaire’s attempt to bestow a poetic nature to Orphism’s provenance, the three founders of the movement were in fact rigidly scientific in their approach to painting. Although indeed influenced by music’s abstract qualities, they were not attempting to engage in anything spiritual or magical. They were exploring specific theories regarding the effects of color on human emotion.

Sonia Delaunay -Rythme coloré, 1952. Oil on canvas. 105.9 × 194.6 cm. © Sonia Delaunay

Separating Colors From Objects

The Orphists were interested in the unique qualities possessed by the elements of line, color and form aside from the aesthetic phenomena with which they’re commonly associated. They were specifically inspired by the work of three art theorists, each of which deconstructed elements of painting in order to analyze the potential power of its individual elements. The first was Paul Signac, a passionate follower of Pointillism and its inventor Georges Seurat. Signac wrote extensively on Divisionism, the theory behind Pointillism, which revealed that colors could achieve a greater effect if mixed in the viewer’s eyes rather than on the canvas.

The Orphists’ second influence was the French academic Charles Henry, whose theories on emotional association suggested that line, color and form had autonomous abstract associations within human consciousness that could be separated from objective subject matter. Most significantly, the Orphists were influenced by the color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, that scientist whose name is on the Eiffel Tower, which analyzed the effects different colors had on human observers as well as on each other, and included an effect called Chevreul's Illusion, the sense that there appears to be a bright line separating two intense, adjacent colors.

Robert Delaunay - Rhythm n°1, 1938. Oil on canvas. 529 x 592 cm. Mural decoration for the Salon des Tuileries. Musée d'Art Moderne de la ville de Paris.

Simultaneous Contrast

Chevreul’s most influential work was in the realm of something called Simultaneous Contrast, which looked at the effects different colors had on each other. While working for a dye company, Chevreul noticed that colors looked different depending on what other colors they happened to be next to. This relative comparison inspired him to test various color combinations and led to many observations about the psychological effects the color combinations had on human observers.

This theory that different color combinations could produce distinct emotional reactions in human observers had a profound effect on the Orphists. They explored the so-called “vibrational” effects of various color combinations, noting that visually different color combinations contributed to a sense of motion, leading some to compare their works to those of the Futurists, who were also deeply concerned with motion and speed. By marrying the Neo-Impressionistic theories of Divisionism with the reduced geometric visual language of Cubism, and then adding bright contrasting colors in an effort to create a sense of motion and psychological sensation, the Orphists created a unique aesthetic combination that soon evolved into one of the first purely abstract art movements.

Franz Kupka - Dynamic Disks, 1931-33. Gouache on paper. 27.9 x 27.9 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Bequest, Richard S. Zeisler, 2007. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Who Were The Orphists?

The three painters attributed with founding the movement were Franz Kupka, Sonia Delaunay and Sonia’s husband Robert Delaunay. These three painters created the aesthetic style that has become iconic to the movement, and they most successfully communicated the theoretical basis for their work. Several other artists also experimented with the style, including Francis Picabia, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger and the American abstract painter Patrick Henry Bruce. But most of those painters soon abandoned the trend for other emerging styles.

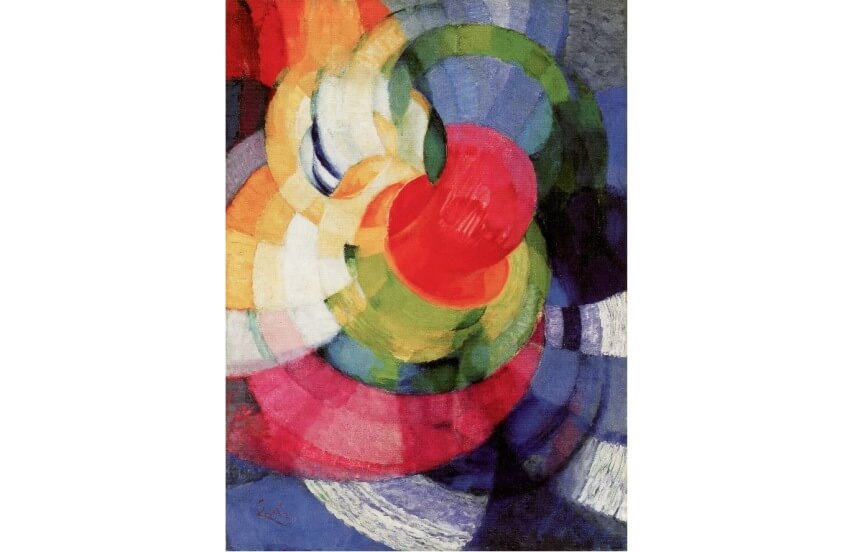

Franz Kupka - Disks of Newton (Study for "Fugue in Two Colors"), 1912. Oil on canvas. 100.3 x 73.7cm. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Franz Kupka

This Austria-Hungary-born painter began his career as an illustrator of books. Although he was associated with groups of artists including the Futurists, the Cubists and the Puteaux Group, he avoided any direct connection to any movement or style. His devotion to understanding the effects and objective properties of color led him to create his own color wheels based on similar earlier work by Isaac Newton. In 1912, Kupka painted what at the time was considered to be a seminal Orphist work, Fugue in Two Colors. Earlier that same year, in preparation for that painting, he painted what to many people has since become an even more famous painting, Disks of Newton (Study for “Fugue in Two Colors”). Although he was in his mid-40s, Kupka volunteered to fight in World War I. After the war he continued to paint, also continuing to explore geometry, color, form and line and their abstract abilities to affect human emotion.

Sonia Delaunay -Prismes electriques, 1914. Oil on canvas. 250 × 250 cm. Musée national d'art moderne (MNAM), Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Sonia Delaunay

Born Sarah Stern in Ukraine and educated in art in Germany, Sonia Delaunay moved to Paris to become an artist in 1905. She soon married the art dealer Wilhelm Uhde, and spent a great deal of time at his gallery. There she met the well-established, successful painter Robert Delaunay. Sonia divorced her first husband and married Robert Delaunay in 1909. Together they built on Robert Delaunay’s radical studies of color, leading directly to the development of the unique style that has become Orphism.

Sonia was not only a prolific and influential painter; she also worked as a designer in the worlds of fashion, theater and industry. She continued to focus on the intrinsic power of colors and geometric forms to affect human perception and communicate abstract truths for the entirety of her career. In 1964, Sonia enjoyed a retrospective of her work at the Louvre, becoming the first living female artist to be so honored.

Sonia Delaunay - Fashion Illustration, 1925. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 38 x 55.6 cm.

Robert Delaunay

An avid researcher, insightful theorist and talented painter, Robert Delaunay was interested in color from the earliest stages of his development. At the age of only 19, Delaunay was already exhibiting mature work. His paintings at that time were inspired by Divisionist theory and were among the works derided by the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles as being composed of “little cubes” of color, a comment that led to the later coining of the term Cubism.

Delaunay himself didn’t associate with any particular style of painting, and he resisted his description as an Orphist throughout his career. Nonetheless, he did interact personally and professionally with many of the artists associated with Cubism and various simultaneous abstract art movements. His focus was always intently on color. Even as he painted works in the Analytic Cubist style, his vibrant colors were at odds with the other painters working with similar ideas at the time.

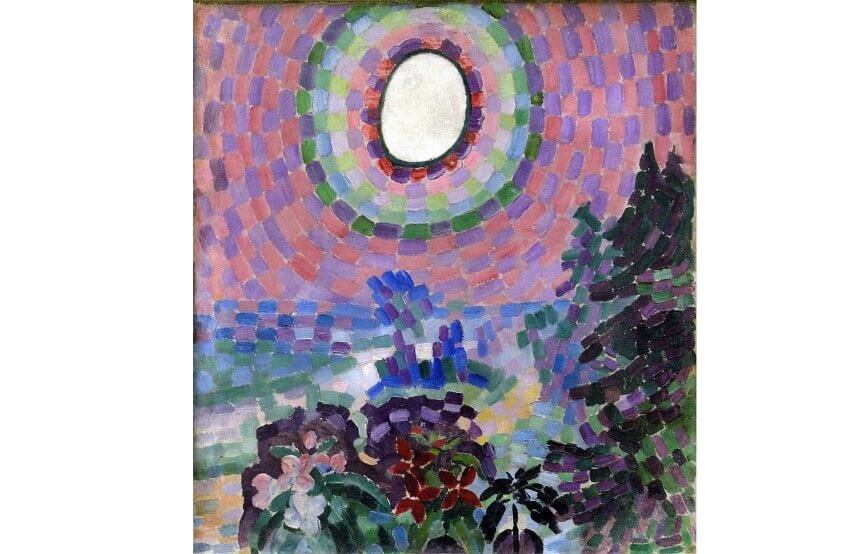

Robert Delaunay - Paysage au disque, 1907. Oil on canvas. 55 x 46 cm. Musée national d'art moderne (MNAM), Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Legacy of Orphism

These visionaries believed in the power of color to express emotions and sensations independent of associations with representational forms. They were experimentalists and believers in pure abstraction as a way of communicating the deepest aspects of the human experience. Like other luminaries of the early 20th Century, such as Picasso and Kandinsky, Kupka and the Delaunays broke new ground in creating a practice that effectively helped introduce pure abstraction to the world. Orphism was short-lived for most artists, but these three founders of the movement practiced it until their deaths. They helped to inspire other movements such as Lyrical and Geometric Abstraction, and are still considered inspirations to many abstract artists today.

Featured Image: Robert Delaunay - La ville de Paris, 1911. Oil on canvas. 47.05 x 67.8 in. The Toledo Museum of Art

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio