Key Figures of the Pattern and Decoration Movement

The Pattern and Decoration movement holds a special place in contemporary art history. Emerging out of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1960s, Pattern and Decoration declared itself as a sort of “third method” between figuration and abstraction. The leaders of the movement recognized that the instinct towards making decorative art has been an essential aspect of every human culture since the beginning of civilization. Yet, they also realized that patriarchal Western civilization had for some reason, somewhere along the way, adopted the stance that decorative arts should be subjugated as less important and less serious than other so-called Fine Arts. The founders of the Pattern and Decoration Movement flatly rejected that assumption, declaring their formalist approach to decorative work to be equally as relevant, meaningful, and historically important as any other aesthetic position. The overarching philosophy of the Pattern and Decoration movement was spelled out in 1978 by two of the founders of the movement—Valerie Jaudon and Joyce Kozloff—in their wonderfully bombastic manifesto, Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture. Its opening paragraph states, “As feminists and artists exploring the decorative in our own paintings, we were curious about the pejorative use of the word ‘decorative’ in the contemporary art world. In rereading the basic texts of Modern Art, we came to realize that the prejudice against the decorative has a long history and is based on hierarchies: fine art above decorative art, Western art above non-Western art, men’s art above women’s art. By focusing on these hierarchies we discovered a disturbing belief system based on the moral superiority of the art of Western civilization.” The leaders of the movement thus set out to consign those outdated and useless hierarchies to the ash heap of history. The legacy of their work is one of visceral beauty and intellectual wonder. Only now, in fact, are audiences truly absorbing the power of this vital movement, and the role it continues to play today in making the contemporary art field more equitable, more open minded, and more complete.

Five Leaders of the Movement

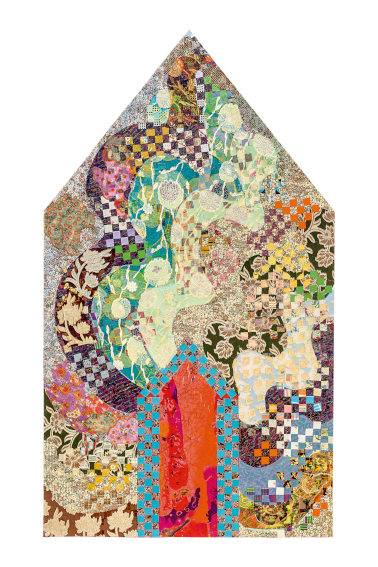

As early as 1960, Miriam Schapiro was abandoning the dominant aesthetic trends of the time in favor of discovering a uniquely personal visual voice, one based largely on her identity as a woman. Her first proto-Feminist works were her “Shrines,” which acted as a sort of sanctified bridge between femininity, spirituality, and the compartmentalized Modernist language of the grid. She went on to create several other distinctively Feminist bodies of work, including her monumental “Fans,” and a series of hard-edged, geometric abstract works that present bold, luminous images of archetypal female symbology. In 1973, Schapiro participated in “Womanhouse,” one of the most important Feminist artworks of all time. She also later coined the term “Femmage” for her distinctive method of blending Fine Art techniques like collage and assemblage with craft techniques like sewing.

Miriam Schapiro - Dormer, 1979. Acrylic, textiles, paper on canvas. 178,5 x 102 cm. Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst Aachen. Photo: Carl Brunn / Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst Aachen © Estate of Miriam Schapiro / Bildrecht Wien, 2019.

Joyce Kozloffhad her epiphany about the historical diminishment of decorative arts after living in Mexico and then visiting Morocco and Turkey in the early 1970s. Inspired by how the ancient aesthetic traditions in these places were still alive and thriving in everyday life, she pursued her own ideas on this topic on a number of different fronts. She began making large-scale paintings and multi-media installations that employed methods and materials traditionally assigned to decorative crafts; she joined the Heresies Collective, which participated in Feminist social actions and published the journal HERESIES: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics; and she co-wrote the aforementioned Pattern and Decoration manifesto. In the decades since founding the movement, Kozloff has become more active in the public art field, and has developed a distinctive aesthetic voice founded on the idea of mapping, both in a cartographical and a cultural sense.

Joyce Kozloff - If I Were a Botanist Mediterranean. 3 panels of a 9 panel piece. Acrylic, archival digital inkjet printing, and collage on canvas. 54″ x 360″. © Joyce Kozloff

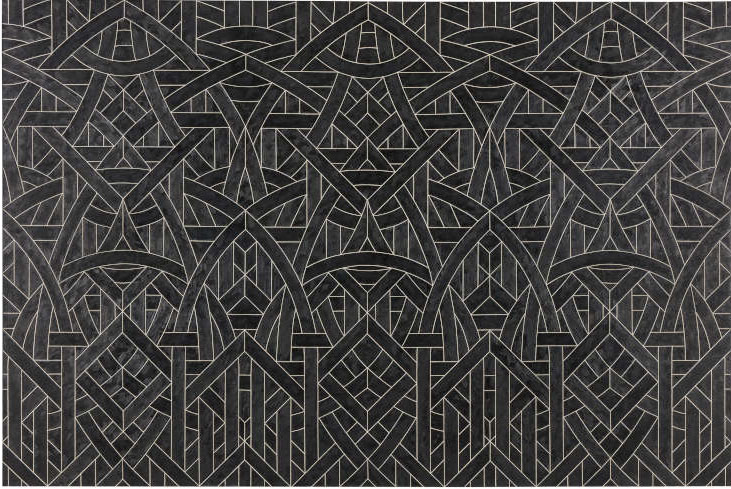

In addition to co-writing the Pattern and Decoration manifesto, Valerie Jaudon established herself as one of the most confident aesthetic voices of the movement. Her distinctive style blends calligraphic markings with patterns and designs evocative of Middle Eastern decorative styles. In addition to her paintings and works on paper, Jaudon has executed more than a dozen large-scale public projects, from inlaid floors, to ceiling murals, to massive public park installations. The largest of these projects is the monumental “Filippine Garden (2004), a cement path on the grounds of the Federal Courthouse in St. Louis, Missouri. Its composition is typical of her oeuvre in the way that it seems at once familiar and exotic; its roots beautifully unclear, it blends seamlessly into the natural and architectural setting.

Valerie Jaudon - Hattiesburg, 1979. Oil on canvas. 223,5 x 335,5 cm. Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst Aachen. Photo: Carl Brunn / Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst Aachen. © Bildrecht Wien, 2019.

As early as the late 1960s, Susan Michod began developing an aesthetic position midway between Modernist abstraction and the aesthetic tendencies of various ancient indigenous traditions. Her work straddles the line between these two cooperative perspectives, recalling both the hypnotic wonder of Op Art and the somber geometric patterns native to the art forms of Pre-Columbian Central America. In addition to her contributions she made to the Pattern and Decoration Movement as an artist, Michod was a co-founder of the Artemisia Gallery in Chicago, an influential exhibition space for female artists, where such luminaries as Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff and Nancy Spero, amongst many others, showed their early work.

Susan Michod - Azteca Shroud, 2003. Acrylic on paper. 40 x 30 in. © Susan Michod

Along with Miriam Schapiro, Robert Kushner helped organize some of the earliest Pattern and Decoration exhibitions. Kushner came to the art field from the world of advertising illustration, which he left in 1961 after seeing an exhibition of the work of Franz Kline. It took him some years, however, before he gained the confidence to develop his own unique voice. After experimenting with a range of styles, from Abstract Expressionism, to Minimalism, to Color Field Painting, he eventually abandoned the prevailing trends to take a personal stylistic leap in 1972, applying stenciled “shapes” to his canvases in an “all-over” pattern. Throughout the 1970s, these patterned stencil paintings evolved to include more floral imagery, embracing a middle-ground between formalist celebrations of decoration and figurative representations of symmetrical gardens.

Robert Kushner - Pink Leaves, 1979. Acrylic, various textiles. 205 x 330,5 cm. Courtesy Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest, Schenkung Peter und Irene Ludwig / donation of Peter and Irene Ludwig. Photo: Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest. © Robert Kushner

Featured image: Susan Michod - Untitled, 1977. Watercolor on paper. 30 in. x 22.5 in. (76.2 cm x 57.15 cm). RoGallery in Long Island City, NY. © Susan Michod

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio