How Space Stands Still in Paul Feeley's Art

Feb 10, 2021

The art of Paul Feeley reminds me of the similarities great abstract art shares with great music. Just as one might hear the Gymnopédies of Erik Satie performed over and over again by different musicians in different settings and still feel something new and special each time, a viewer could attend any number of different Feeley exhibitions and continually experience new joys. What makes repeat consumption tolerable, even enjoyable, with certain works of art has to do with how readily the artwork yields to relativity—a painting or song that lets itself adapt to the evolving circumstances of the audience never gets old, despite its age. Feeley made that kind of work. His paintings and sculptures interact with whatever is around them in an almost living way. His compositions read like puzzles, or visual toys for the mind. Simple yet confident, a Feeley painting gives you something to zone out with: to look at while taking a break from looking. When Feeley was alive and making work, his paintings were on view pretty much constantly. Between 1950 and 1976, he had a New York solo show almost every year, including a memorial retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1968, two years after his death. Back in 2015, The Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, mounted what so far has been the most ambitious Feeley retrospective of the 21st century. Titled Imperfections by Chance, that exhibition included 58 works spanning the entirety of his career. Walking through it was like the grown-up version of visiting a funhouse. Some of his works pose riddles; others inspire laughter; still others seem to offer a window into another dimension of thought and feeling. For my money, we could all use a good Feeley exhibition right about now, just to get us into a fresh head space. The best chance we have this year will be in London, at Paul Feeley: Space Stands Still, opening at Waddington Custot gallery in April. With more than 20 works on view, including both paintings and sculptures, it promises to offer a welcome respite for anyone looking for some visual and mental relief from our ongoing apocalypses.

Art in Relief

My personal affinity for Paul Feeley has to do with the fact that I tend to turn to art for existential relief. Abstract art appeals to me the most because it can contain everything and nothing, so I can see whatever I want in it. I can interject my own meaning into it, and can go along on a gurney with it without being colonized by it. Feeley died before I was born, but I have a feeling he and I would have agreed that he intended for his art to be consumed in this way. His works offer unpretentious, quiet moments of humanity and clarity. Their handmade quality shows vulnerability, while their whimsical presence betrays an artist who did not take art too seriously. He clearly wanted the work to be open, and to invite viewers into a contemplative space, rather than asserting something alien onto them.

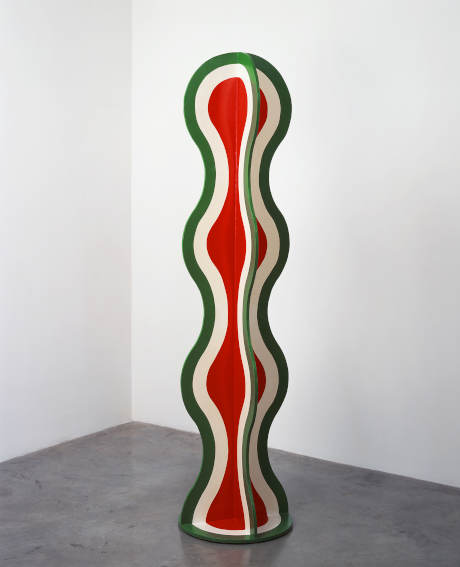

Paul Feeley - El Raki, 1965. Oil based enamel on wood. Courtesy the Estate of Paul Feeley and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

It is interesting to me that Feeley turned out to make work like this considering the people he was around at the height of his career. In the late 1940s, Helen Frankenthaler was a student of his at Bennington College in Vermont, where Feeley taught for 26 years. They became friends, and through Frankenthaler he befriend Jackson Pollock, Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis and Clement Greenberg, among others. How unlike those other people Feeley was—unpretentious, vulnerable, whimsical and quiet are not words I would use to describe the rest of them, except perhaps Frankenthaler. My only guess about how Feeley arrived at such a unique approach at art making is that it has something to do with his service in the U.S. Marines in World War II. Barely a blip on his CV, this experience seems to have changed Feeley. Looking at his expressionistic, figurative work before and his evolution to the distinctly gentle, universal, anthropomorphic abstraction he created afterwards, it most certainly changed the way he made art.

Paul Feeley - El Asich, 1965. Oil-based enamel on wood, 188 x 46 x 44 cm. Courtesy the Estate of Paul Feeley and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

Stillness in Space

The subtitle of Paul Feeley: Space Stands Still was derived from a statement Feeley once made about his work. He said, “space stands still” in his compositions. I admit to being a little confused by this statement at first. I thought space was always still, and various forces compelled objects to travel through space in different ways, causing viewers, if there are any, to perceive movement, or a lack of stillness. Then I realized I was taking Feeley too literally. What he was trying to say had to do less with the forms in his work or the actual works themselves, and more to do with differentiating himself from his contemporaries the Abstract Expressionists, also known as the “action painters.” Feeley was declaring himself an “in-action painter.” Like the artist John McLaughlin, who, after fighting in both World War I and II embraced meditation and then helped pioneer the Light and Space Movement, Feeley was making the point that his works are intended to be an expression of the void.

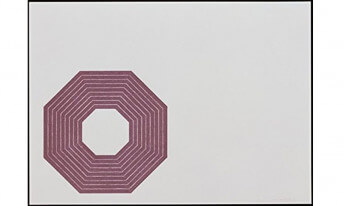

Paul Feeley - Cor Caroli, 1965. Oil-based enamel on wood. Courtesy the Estate of Paul Feeley and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Inhabitants of the cosmic void, such as stars, provided Feeley with the names for many of his works, such as “Alruccabah” (1964) and “Cor Caroli” (1965). I could argue that some of these works, especially “Cor Caroli,” actually resemble the appearance of a shining star seen from afar, but I think Feeley was being more allegorical with his titles. Earthbound viewers perceive stars to be still in the sky, and yet they also twinkle, a tiny reminder of the unimaginable cosmic forces at work on their surface and stored within their core. Naming his works after stars was a reminder from Feeley that the void is not empty. Inaction is not the opposite of creative power, but the source of all creative potential.

Paul Feeley: Space Stands Still will be on view from 20 April through 1 June 2021 at Waddington Custot gallery in London.

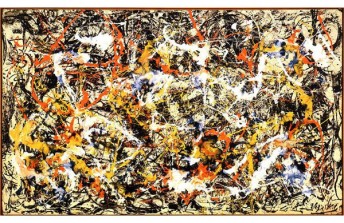

Featured image: Paul Feeley - Germanicus, 1960, Oil-based enamel on canvas, 172.7 x 241.3 cm. Courtesy the Estate of Paul Feeley and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio