When Piero Manzoni Made Abstract Art with Achromes

On 14 February 2019, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles will open an exhibition focused on the “Achromes” of Piero Manzoni. Titled Piero Manzoni: Materials of His Time, and curated by Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, director of the Piero Manzoni Foundation in Milan, the exhibition presents a rare opportunity for U.S. audiences to come face to face with one a legendary body of conceptual art. Begun in 1957, the Achromes were instrumental in exhilarating the Italian avant-garde during the so-called “Italian economic miracle,” a time of reconstruction after World War II when the daily life and living standards of Italians changed faster and more dramatically than ever before. It was a time when millions of economic migrants flowed from the country to the cities, causing irrevocable changes to architecture, traffic flow, eating and drinking habits, and of course arts and culture. Born in 1933, Manzoni came into his own as an artist in the midst of this time. His shattered world was marked by trauma, uncertainty, and an ever-present fear of nuclear war. His first exhibition, held in 1956, consisted of haunting, figurative paintings of everyday objects reduced to shadow, set against backgrounds of fiery, radioactive glows. However, everything about his method changed in 1957, when an exhibition of blue monochrome paintings by Yves Klein came to Milan. Manzoni saw the exhibition as a call to arms. He abandoned his search for the painted image, devoting himself instead to a search for what could be considered true art, or art that embodied the originality and timelessness of nature. His Achromes were a first step towards something completely original. They led Manzoni towards the development of every other body of work he created, and set him on a path towards becoming one of the most influential artists of the 20th Century.

The Colorless Surface

Manzoni had been making and exhibiting solid white artworks – what we now call his “Achrome” series – for two years before he finally came up with the name “Superfici Acrome,” or Colorless Surface, in 1959. There is irony in the name. Scientists consider the absence of color to be blackness, not whiteness, since color requires light in order to be perceived, and black absorbs all light. The earliest so-called Colorless Surfaces Manzoni made were created by simply covering sheets of canvas with white gesso, a chalky white pigment normally used by painters to prepare a surface for painting. By simply applying gesso to a canvas and calling it finished, Manzoni one-upped Yves Klein, who had achieved much by reducing painting to a single hue, but still left room for simplification.

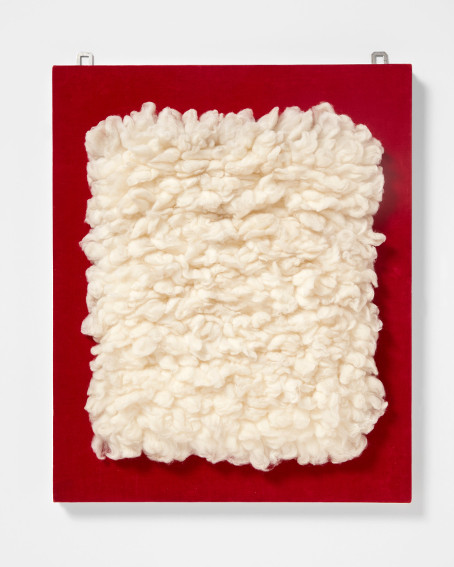

Piero Manzoni - Achrome, 1961. Synthetic fiber. 42 x 33 cm / 16 1/2 x 13 in. Herning Museum of Contemporary Art (HEART). Photo: Søren Krogh. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

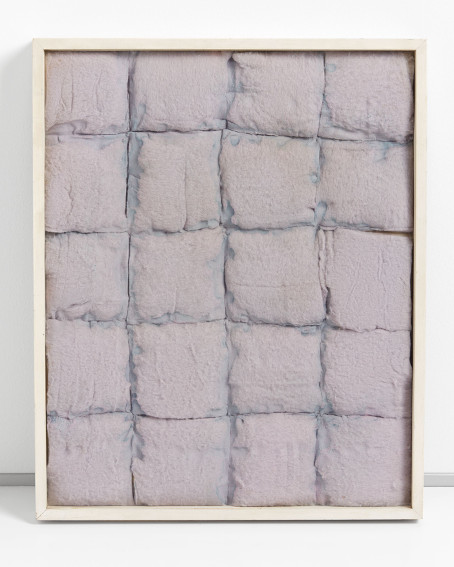

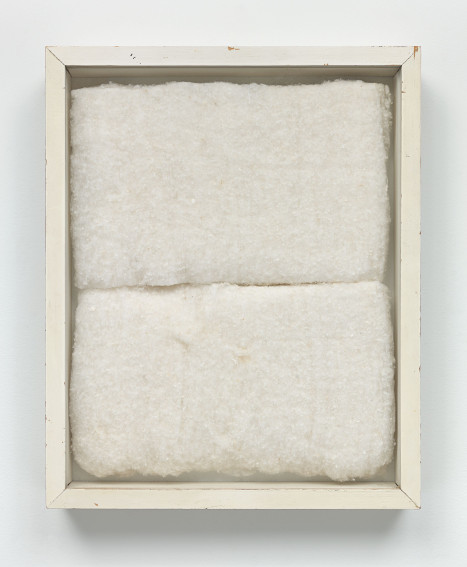

Even after eliminating hue altogether, however, Manzoni found that the mark of his hand was still visible in the work, since he had applied the gesso to the surface. He longed for something irreproducible, truly original, which meant he had to take himself out of the work and let nature express itself free from his interference. For his next Achromes he poured liquid kaolin, a white clay-like substance, onto sheets of raw canvas then let the weight of the medium manipulate the surface at will. Over time, the medium caused the surface to fold and warp in ways similar to the water-worn bed of a river or the wind swept ridges of a sandy desert. But even this intervention seemed too much for Manzoni. In his search for an Achrome that completely hid evidence of his presence, he covered bread rolls with kaolin, coated sheets of Polystyrene with phosphorescent paint, and sewed sections of white canvas together into a grid. His most successful attempts were perhaps the Achromes that utilized materials that were already white, such as cotton, fiberglass, and rabbit fur. For those, he simply organized compositions then let the material speak for itself.

Piero Manzoni - Achrome, 1961. Square cotton wading and cobalt chloride. 56.2 x 47.2 cm / 22 1/8 x 18 5/8 in. Herning Museum of Contemporary Art (HEART). Photo: Søren Krogh. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

Truly True

What Manzoni hoped to accomplish with his “Superfici Acrome” was something that was truly true: the artistic expression of tautology – something so original that it continues expressing its inherent truth redundantly forever regardless of how anyone reacts to it. Gravity is tautological, as is the passage of time. It is undeniable, authentic, and completely unique. Some artists think the creation of tautological art is a futile, impossible goal. They believe that as soon as a human idea manifests in the physical world it reveals its artificiality, becoming a parody of nature and truth rather than a representative of it. Manzoni was not so cynical, however. He believed it was possible to create inimitable works of art, and besides his Achromes, he strived to achieve this goal with several other bodies of work.

Piero Manzoni - Achrome, c. 1960. Cotton wool. 31 x 25 cm / 12 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. Courtesy Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

In a series called “Fiato d'Artista” (Breath of an Artist), he sold balloons that could either be blown up by the buyer or blown up by the artist, with the price rising accordingly in the second case. The breath trapped within each balloon was irreproducible, and the exact size and shape of each balloon was unique. Best of all, these works faded with time, eventually releasing their precious commodity through a natural process of self-destruction. In another series called “Consumption of Art by the Art-Devouring Public,” Manzoni printed his own fingerprint onto eggs which he then invited viewers to consume with him. For his “Sculture viventi” (Living Sculptures), he enlisted human beings to allow him to sign their bodies. And in the case of his most infamous series, “Merda d’Artista” (Artist Shit), Manzoni dried and packaged 90 cans of his own excrement then sold them for the current price of gold. Perhaps the closest Manzoni ever came to achieving his goal of inimitability, however, was when he created the “Socle du Monde” (Pedestal of the World), an upside down plinth set in a field in Denmark. By presenting the entire world as a work of art, this piece suggests that only by accepting the final authority of nature can an artist truly express its truth.

Piero Manzoni Materials of His Time will be on view at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles from 14 February through 7 April 2019.

Featured image: Piero Manzoni - Achrome, 1961. Straw, reflective powder and kaolin, burnt wooden base. 68.3 x 45.8 x 44.5 cm / 26 7/8 x 18 x 17 1/2 in. Herning Museum of Contemporary Art (HEART). Photo: Søren Krogh. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

By Phillip Barcio