What is Rayonism?

Oct 1, 2018

Rayonism was a Russian avant-garde art movement founded by the painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov around 1911. The movement was based on the concept that material objects are really only starting points for the emanation of light, and that that light was the only subject worth painting. The word Rayonism, or, as many Russians pronounce it, Rayism, comes from the Russian word лучизма, or luchizma, which means “irradiation.” Their admiration for the qualities of irradiation seems to have come out of a general sort of global fanaticism for what was at the time a relatively new invention: x-rays. In 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen accidentally discovered that barium platinocyanide glowed even while enclosed inside of cardboard. That realization—that particles of light could pass right through solid objects—was shocking to scientists, and it caused many ordinary people to take the philosophical leap that as a material, light must therefore have primacy over so-called solid objects. The Rayonists surmised that it is thus a waste of time to paint so called reality, when in fact all objects and animals and people and landscapes are secondary to the light energy that illuminates them, dwells within them, and passes through them. This light, they believed, was the true underlying force that bound the universe together. As Larionov once described it, “Rayism is the painting of space revealed not by the contours of objects, not even by their formal colorings, but by the ceaseless and intense drama of the rays that constitute the unity of all things.”

The Future is Behind Us

We mostly talk about Rayonism in terms of aesthetics. But in addition to its very specific visual qualities, Rayonism was also important as a distinctly progressive cultural movement. In fact it could be argued that the cultural aspects of the movement came first, and that Rayonism was simply a way of expressing what everybody was already feeling. It represented several social philosophies: Modernism, anti-Western cultural superiority, anti-individuality, and the impossibility of judging art in relation to time. The Rayonist Manifesto, published in 1913, spends most of its time not describing the particulars of what a Rayonist painting might look like, but rather goes on at length about the fact that the Russian avant-garde is beyond the limited constraints of the past, is living proof that Western culture is corrupt, and is beyond the limited intelligence of most of the general public. Literally it states, “art cannot be examined from the point of view of time...we reject individuality as having no meaning for the examination of a work of art...long live the beautiful East…...we are against the West, which is vulgarizing our Eastern forms...and which is bringing down the level of everything.”

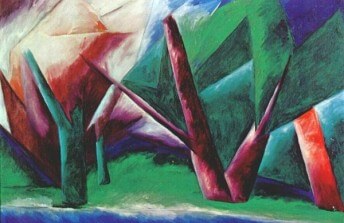

Natalia Goncharova - Yellow and Green Forest, 1913

Just as they insulted Western culture, however, the Rayonists also acknowledged that their new style of painting is in fact the “synthesis” of cubism, futurism, and orphism, three distinctively Western styles. They called this concept всечество, or vsechestvo, which means ubiquity. The English word they came up to describe it was “everythingism.” The core idea of everythingism is that styles and movements rise and fall so quickly and travel the world so rapidly that everything is happening all at once everywhere, creating an amalgam of ideas flourishing all at once all over the globe. The Rayonists blamed this phenomenon for the appearance that they had derived Rayonism from Western styles, and then further defied the homogenization that inevitably came from everythingism by infusing their style with elements of Russian folk art. They selected Russian objects and Russian livestock from which to paint the light emanating forth. The color palette they used was traditionally Russian. And they kept their painting style primitive to show solidarity with who they called the “ordinary house painters” of Russia.

Mikhail Larionov - Bull's Head, 1913

The Light from Spatial Forms

Despite all of the political and social rhetoric that underpinned the Rayinst manifesto, the most lasting legacy of the Rayonist movement is indeed in the realm of plastic arts. Rayonist paintings are most often defined not by philosophy, but visually, by the sharp, angular, colored lines on the surface, which signify rays of light. Nonetheless, some Rayonist compositions are more philosophical, and more abstract, than others. There are two basic categories of Rayonism: Realistic Rayonism and Pneumo-Rayonism. In a Realistic Rayonist painting, the rays of light (represented by the angled lines) emanate off of an actual figurative object, like a rooster or a drinking glass. In a Pneumo-Rayonist painting, the objects from which the light emanated have completely decomposed, leaving behind only the light. The individuality of the subject has thus been rendered irrelevant, eradicating the self, the terrible “I,” in keeping with the philosophies of the manifesto.

Natalia Goncharova - Rayonist Lilies, 1913

Another highly philosophical aspect of Rayonist paintings is something called фактура, or faktura. Essentially, this word means texture. But as it relates to Rayonist paintings the concept goes a bit deeper than that. It is the idea that every material has certain surface qualities that express its essence. Those surface qualities include texture, of course, but they also include more esoteric things. Irradiation is a surface quality; so is color; so is tint; so is shape; so are the feelings that an object inspires in a viewer. All of these things are part of faktura. The concept of faktura is essential to Rayonism because it relates to the non-objectivity of the solid world. The ethos of these Russian artists was shaped by war, famine, poverty, and a long struggle for equality and justice. They believed personal identity and individualism to be deplorable outgrowths of egotism, which led people to do terrible things to each other. For them, Rayonism offered an abstract way to talk about the primacy of what is immaterial and universal. So next time you admire the rays of light in one of their paintings, do not think only about the sharp angled lines. Think also about faktura: consider how far its roots have pervaded, and how vital its mysteries are to our contemporary understanding of the potential power of abstract art.

Featured image: Mikhail Larionov - Rayonist Sausages and Mackerel, 1912

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio