The Architecture of Abstraction - An Interview with Artist Robert Baribeau

Mar 17, 2021

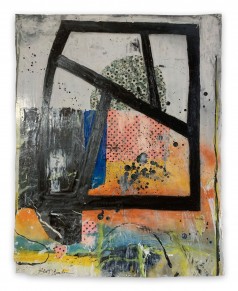

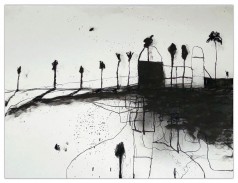

Oregon-born, New York-based abstract artist Robert Baribeau has weathered innumerable aesthetic trends throughout his 47-year exhibition history. When his first New York show opened in 1979, at Allan Stone Gallery, second wave Pop was just beginning and figuration was coming on strong. The scrawled, expressionistic, impasto abstractions Baribeau brought to the party stood out for their dogged resistance to simple description. As art field fashions came and went, Baribeau stayed true to himself. What is most obvious about his now-instantly-recognizable visual language is its unwavering sense of confidence—as if every painting he makes is totally assured of its own potential to attract the human eye to itself. A recipient of a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, a National Endowment for the Arts Grant, a Florence Saltzman-Heidel Foundation Grant, and a Pratt Institute Art Department Grant/Fellowship, Baribeau has seen his works exhibited in gallery and museum exhibitions across the United States, and his work reviewed in such outlets as The New York Times, Artforum, New American Paintings, and Art News. He recently joined me on the phone from his home in Stanfordville, New York, to talk about his work and life.

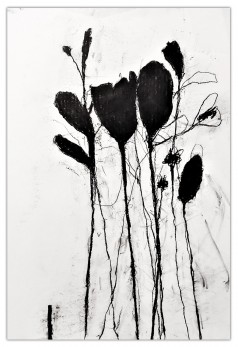

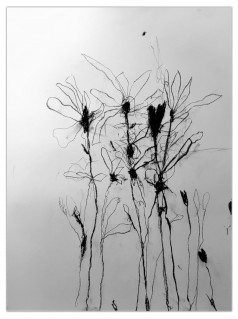

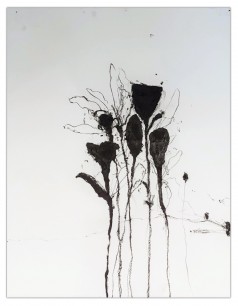

Once in a long while, narrative content appears in your work, such as your flower portraits. For the most part though, would you describe yourself as an abstract artist?

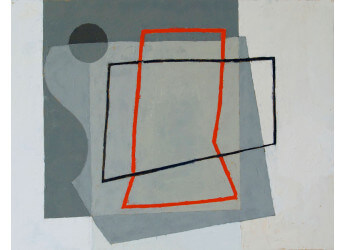

I’m more into formal things. I’ve built up a vocabulary over the years, mostly by trial and error, just trying to improve myself. The vocabulary I’ve built up, I add to it, or try to. It’s almost like painting one painting—bits and parts of former things come back. A lot of my interests lie in architecture. I would have gone into it, but the thing about architecture is that I’m not a real team player. I don’t think that would have worked out.

Besides architecture, what else has influenced your visual language?

Some of my favorite painters are (Richard) Diebenkorn and (Robert) Rauschenberg. I don’t know if you can tell the influence, but that’s where I got that layering things over each other, then layering clear vinyl and covering it with oil paint. The best thing I do every day is I go out to the studio. That’s where I find the best of me. It’s kind of about listening to my own voice talk.

How do you get started on a new piece?

It’s always something new for me. It’s mostly about the materials actually. I try to incorporate a lot of heavy paint and fabric. I do like just the paint itself. I like to build up the paintings with the thick gel I use, or I use spray paint, or dispersed pigments, mostly acrylic. I like acrylic because it’s more contemporary technology I guess, and some of those thick paintings I have would never dry with oils.

Your compositions seem grounded in landscape; foreground, background; what is the source of your interest in landscape painting?

I grew up on a farm in Oregon and loved the landscape, and even aerial views of things, which relates to Diebenkorn again.

Did you ever talk to Diebenkorn?

I saw him at a show in the 90s. He was too busy to talk. He’s about six foot three, and he has those big paintings. He’s from Portland, too. So is Rothko. I was born in Aberdeen, Washington. Motherwell was from there. There’s still an active art scene there I think.

Artist Robert Baribeau with one of his paintings during his opening at the Allan Stone Gallery

You taught for a while out there.

I taught in Portland, at Pacific Northwest College of Art. I taught drawing and painting.

Was abstraction part of your curriculum?

I did some talks about that. A lot of people didn’t know about those artists, and it’s a good thing to know, I guess. But mostly pretty much my head was in figure and drawing. It’s good to learn how to draw before you do anything else. Places of shapes, sizes and relationships, hand-eye coordination—if you can do that, you can do just about anything. But I let the people do what they wanted to do. It’s surprising sometimes how good they are. It was a lot of fun. People came down from Microsoft and Intel. I taught a rocket scientist. I can brag about that.

How did the checkerboards first enter your visual language?

I found those in a restaurant in Portland—napkins or placeholders or something. I like the mechanical nature of it I guess. I like the contrast, putting the paint on top or underneath; the machine made along with the more organic. It defines a space, too. Your eye will go to it right away, and the organic stuff will lead it away. You have entry points and exits. Like John Chamberlain said, it’s all in the fit. The fit of shapes into each other, and the gravity of a shape, and where it’s located in relation to another shape, and the size of the canvas, too. The borders of a canvas are just as important as everything else. It’s not an obvious thing I don’t think. My instructor at Portland State drummed that into my head and I kept it with me.

How did you get started in New York in the 70s?

I was with Allan Stone since 79, I think. How I ran into him was I was going to Pratt in New York. I used to work at Arthur Brown art store in Manhattan. I got a great discount. My wife worked at Benihana. We lived on w 56th street between 9th and 10th. I was planning on going back to Portland, then I saw Allan’s ad in Art News. I saw a beautiful ad of his, and I went and talked to him. It took a long time to get an appointment. I eventually I had eleven shows there. He’s a great guy. He was patient. He’d go through everything I had, which is a lot of work. Allan was a big collector—huge collector. After he passed away, that’s the only time I ever bought a car for real money. We used to trade cars.

Featured image: Artist Robert Baribeau

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio