Can Robert Motherwell’s “At Five in the Afternoon” Break New Sales Records?

Apr 30, 2018

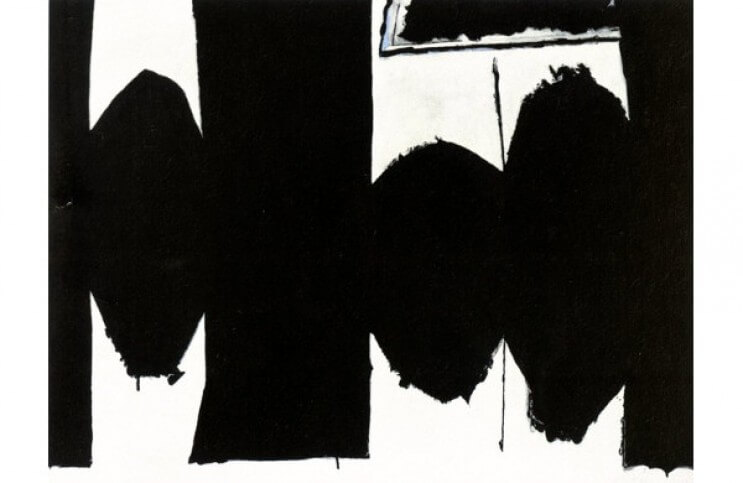

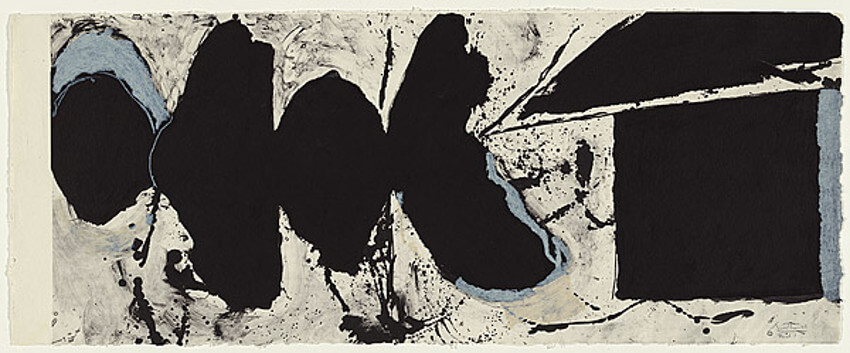

Robert Motherwell’s At Five in the Afternoon may be the most meaningful painting the artist made. In fact, an argument could be made that the painting is the most important Abstract Expressionist work ever painted. Its importance has little to do with its formal qualities, although it is stunning in its authoritative visual presence. The reason this painting is so vital is because of the story it tells about the history of American abstract art. To unravel its provenance and trace the details of its origin is to unlock the secrets of how Abstract Expressionism came into existence, and how Motherwell evolved into its most influential figure. The painting is slated to go to auction for the first time at Phillips auction house in New York, in the 20th and 21st Century Art Sale on 17 May. So profound is its story that Phillips has put an estimate on the painting of between $13 and $16 million—roughly four times the current auction record for a Motherwell.

Elegies to the Spanish Republic

One reason Five in the Afternoon is expected to fetch such a high price is because of the series to which it belongs. It is part of the Elegies to the Spanish Republic series, which Motherwell worked on for more than 30 years, beginning in 1948. Both of his previous auction records came from paintings in this series as well. In 2004, Elegy to the Spanish Republic no. 71 (1961) sold for $2.9 million at Christie’s New York after a high estimate of $800,000. In 2012, Elegy to the Spanish Republic #122 (1972) sold for $3.7 million at Sotheby’s New York after a high estimate of $2.8 million. Most examples from this series are in major museum collections, so for one to come up at auction is rare. In addition to its rarity, At Five in the Afternoon is significant because it is larger than its predecessors. The previous record setters are 71 x 133 inches and 56x 76 inches respectively. At Five in the Afternoon is 90 by 120 inches.

But it is in the story behind this series where the true mystique lies. Motherwell created the first Elegy work in 1947, not as a painting but as an illustration intended to accompany a poem by Harold Rosenberg, which was planned for the magazine Possibilities, which only produced one issue. The Rosenberg poem was dark and surreal. Recalling the drawing he made to accompany it, Motherwell said, “We agreed that I would handwrite the poem in my calligraphy and make a drawing or drawings to go with it and it was to be in black and white. So I began to think about getting the brutality and aggression of his poem in some kind of abstract terms.” The drawing he came up with was titled At Five in the Afternoon, a reference to the brutality of the Spanish Civil War.

Robert Motherwell - At Five in the Afternoon, 1971, © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy

The Plot Thickens

Six year before making that drawing, Motherwell traveled to Mexico with the Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta. On that trip Motherwell met his first wife. It was also on that trip that Matta introduced Motherwell to the Surrealist concept of automatic drawing, or drawing directly from the subconscious. The painters Motherwell associated with back in the United States had been searching for a guiding principle that could help them find a sense of creative freedom. They felt European painters had an intuitive connection to imaginative ways of painting, but that American painters were too caught up in the act of copying their European counterparts. Motherwell felt there could be great promise in automatic drawing.

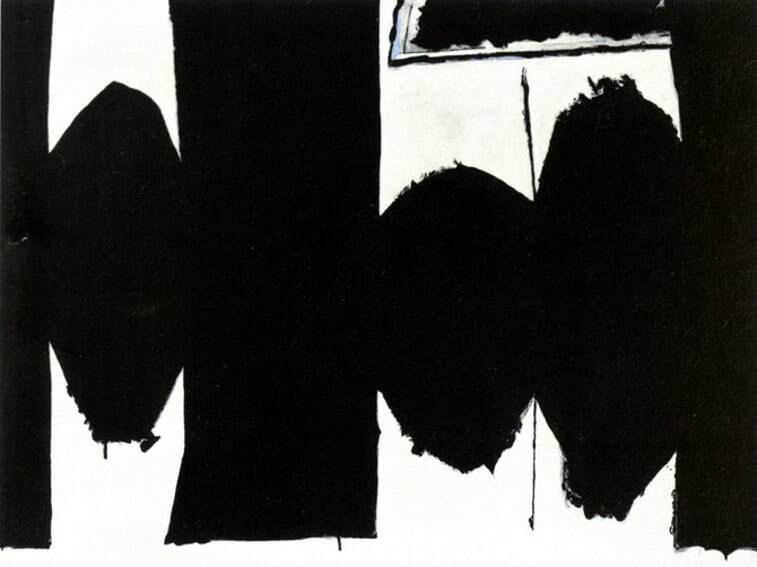

His belief in its potential really took off when Matta introduced Motherwell to Wolfgang Robert Paalen, a German-Austrian painter and philosopher who had relocated to Mexico. Motherwell had a degree in philosophy from Harvard, and connected immediately withPaalen. He studied with Paalen in his studio for several months. That was when that Motherwell began making drawings that contained the swollen, biomorphic shapes and smatterings of splashed ink that would later help define the aesthetic of the Elegy series. When Motherwell finally returned to New York, he explained automatism to the key painters who would soon become associated with Abstract Expressionism. He recalled, “It was then that Baziotes and I went to see Pollock and de Kooning and Hofmann and Kamrowski and Busa … explaining the theory of automatism to everybody because the only way that you could have a movement was that it had some common principle. It sort of all began that way.”

Robert Motherwell - Elegy black black, 1983, © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy

Matters of Life and Death

In 1948, after his first wife left him, Motherwell began drinking heavily and threw himself into his painting. He rediscovered At Five in the Afternoon, the drawing he had done a year before to accompany the Harold Rosenberg poem, and thus decided to begin a new series of paintings based on its black and white palette and distinct arrangement of ovals and lines. Thus the Elegy series began. Motherwell never sold that original 15 x 20 inch drawing. In 1958, he married the abstract expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler, inventor of the “soak-stain” method. After 13 years together, their marriage ended in 1971. In the divorce settlement, Frankenthaler acquired the drawing.

That same year, in an emotional fit of vengeance, Motherwell made a monumental copy of the small drawing for himself. That is the work that is going to auction at Phillips on 17 May. It is the epitome of one of the most iconic series of abstract paintings ever painted, and within the story of its creation are the roots of Abstract Expressionism. Ironically, this monumental painting also stands as a symbol of the end of that movement, as its creation was not born of automatism, but rather it is a figurative copy of an abstract work. Nonetheless, it is a painting that emerged from a deep well of primal human emotion—call it the first work of Concrete Expressionism perhaps.

Featured image: Robert Motherwell - At Five in the Afternoon, 1971, © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio