The Abstract in the Design of Ron Arad

Apr 27, 2017

Since his professional career began in the 1980s, Ron Arad has primarily been recognized as an industrial designer. That is because most things Arad makes are useful in everyday life and can easily be mass-produced. But to say Arad is only a designer is inadequate. He belongs to a lineage that includes the likes of Henri Matisse, Anni Albers, Sonia Delaunay and Donald Judd: creative people whose work often questions, sometimes even erases the boundaries between art, science and design. A peculiarity often emerges in the commercial art world—that of art fairs, galleries and auctions: namely, the desire for aesthetic objects and their makers to be categorized. Buyers and sellers find it more efficient when they know exactly how to describe their commodities. They want to know what is a sculpture and what is a painting, what is a functional object and what is purely aesthetic, what is abstract and what is figurative, what is unique and what is one of thousands. But sometimes such distinctions only get in the way of innovation. For Ron Arad, ideas follow their own trajectories. The end result might manifest as a useful solution to a common problem, and thus evolve into a design for a commercial product. Or, just as likely, an idea could morph into a one-off: something that comes into existence for its own reasons, which even Arad himself may not fully understand.

Red Rover

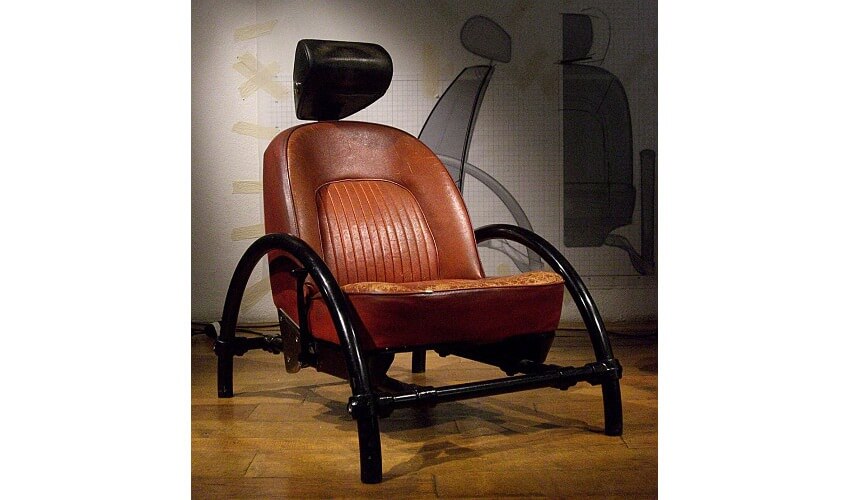

Ron Arad was born in Tel Aviv in 1951. He studied Design in Jerusalem and architecture in London, finishing his formal education in 1979. Two years later he became famous, thanks to what today remains his most iconic piece: the Rover Chair. Fashioned out of two found objects—a red leather front seat from a Rover P6 automobile, and a curved section of steel framing from an industrial animal pen—the Rover Chair was essentially a Readymade, part of the heritage of Marcel Duchamp and Robert Rauschenberg. Both components came straight from a junkyard in northwest London. But it was also a functional, comfortable chair. So the question is whether the Rover Chair should be perceived of as a work of art or design.

In a sense, the market answered that question immediately. Arad received a deluge of orders for the Rover Chair and hundreds were eventually produced and sold. But over the decades the piece has gained a steady following of those who also perceive it as art. It is aesthetically interesting and brings many abstractions to mind. Much can be inferred by the combination of an object intended to control animals with a seat designed for human travel. One represents confinement; the other represents freedom. One expressed human dominance over nature; the other embodies human dominance over technology. Both are smaller components of larger assemblies, and neither was intended for use in an architectural environment. When combined the two elements took on a new character, one that playfully redefines their purpose as things of leisure and beauty.

Ron Arad - Rover Chair, 1981, red front seat from a Rover P6, steel animal pen frame, © 2019 Ron Arad

Ron Arad - Rover Chair, 1981, red front seat from a Rover P6, steel animal pen frame, © 2019 Ron Arad

This Is Not a Chair

In the nearly four decades since his first design success, Ron Arad has created numerous other objects that function as things to sit on. His whimsical chairs and couches are widely coveted. Many come in limited editions and fetch large sums at auction. But in addition to his many products that are obviously intended as seats, he has also made numerous abstract objects that, though they undoubtedly could be sat on, can also simply be enjoyed visually.

Consider his surreal Afterthought, which resembles a melting hand sink; his teardrop-shaped Gomli; or his biomorphic Thumbprint. These are sculptural pieces, which, when read as formal aesthetic objects, can inspire introspection as easily as could a work by Barbara Hepworth. But they also have areas built into them that happen to be perfectly shaped for a human being to sit on. They raise the question of what is more functional: aesthetic joy or relaxation? And they advocate for the possibility that all things derive purpose and meaning not from some objective construct, but from the individual mind of the end user.

Ron Arad - Gomli, 2008, © 2018 Ron Arad (Left) and Afterthought, 2007, Polished aluminum, Photo by Erik and Petra Hesmerg, © 2019 Ron Arad (Right)

Ron Arad - Gomli, 2008, © 2018 Ron Arad (Left) and Afterthought, 2007, Polished aluminum, Photo by Erik and Petra Hesmerg, © 2019 Ron Arad (Right)

Function Less

Two recent aesthetic phenomena Ron Arad produced flip his usual script of taking an aesthetic object and making it functional. These creations take functional components and transform them into things with no utilitarian purpose whatsoever. One is a kinetic abstract sculpture called Spyre, which utilizes industrial components such as steel tubing, motors and cogs to create a whirling, four-jointed metal tower that rotates itself into innumerable configurations. The other is a series called Pressed Flowers, which consists of FIAT 500 automobiles that Arad crushed so they can be hung on the wall.

Says Arad, “I took functional things and turned them into nonfunctional things.” And from that statement a few other thoughts arise: such as whether aesthetic pleasure is in fact functional; and whether there is a difference between meaningful function and meaningless function; and whether altering an object so it functions less could possibly end up causing it to matter more. Ron Arad may just be having fun and may not care how his designs are interpreted. But for us it is the questions his work raises and the ideas it inspires that earns his oeuvre a unique place in the realm of abstract art.

Ron Arad - Spyre, 2016, at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (left) and Pressed Flower Petrol Blue, 2013, crushed Fiat 500 (right)

Ron Arad - Spyre, 2016, at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (left) and Pressed Flower Petrol Blue, 2013, crushed Fiat 500 (right)

Featured image: Ron Arad - Thumbprint, 2007, © 2019 Ron Arad

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio