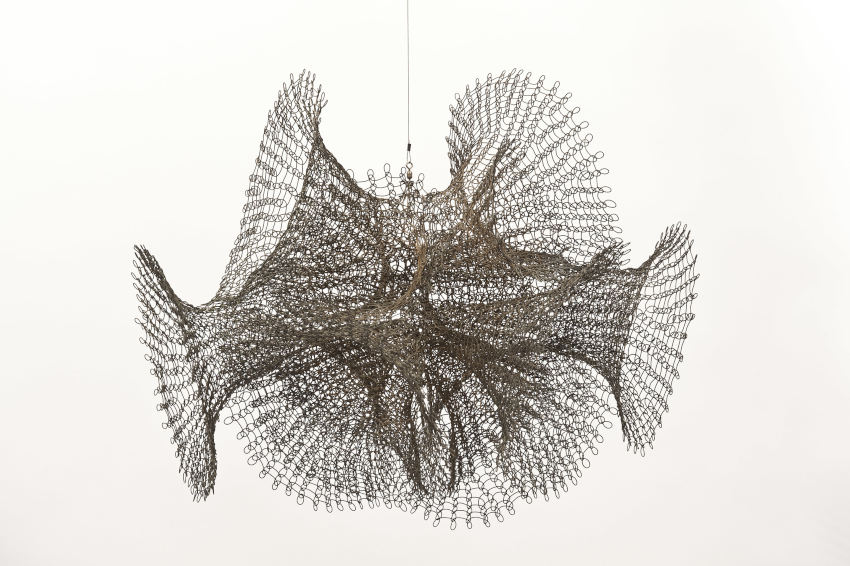

Ruth Asawa’s Hanging Odes to Natural Forms

If you have ever stood in the midst of a Ruth Asawa installation, you understand that there exists an art outside of art; an art forged not from theory, but from direct expression, instinct and ingenuity. Asawa made work that captured the ethereal beauty of nature. She said she was inspired by “seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning, and seeing the sun through the droplets of water suspended from the tips of pine needles while watering my garden.” Such natural phenomena has a poetic existence: it is here, yet fleeting. Asawa captured this paradox in her most famous body of work—hanging, biomorphic, metal forms woven using a technique Asawa learned from indigenous basket makers in Mexico. The forms enclose and define space, while still allowing air and light to flow freely through their boundaries. They can be seen and touched, yet are in some ways as insubstantial as the delicate shadows they cast. They are not natural, but they adopt the visual and metaphysical language of nature. They respect nature and learn from it—making them hopeful ambassadors for our generation. During her own lifetime, Asawa was frequently diminished by misogynistic art critics attempted to diminish her woven forms, because she was female making what to their shallow minds resembled craft objects. Asawa existed outside of the reach of their petty criticism. Her work did not need official validation; it only needed to find its audience. That is finally happening now, six years after her death. David Zwirner gallery recently signed on to represent her estate, a boost that will bring her work much deserved global attention. Perhaps equally impactful, Asawa was recently memorialized in a Google doodle to kick off Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in the United States. The doodle showed five of her biomorphic metal sculptures spelling out the word Google, with Asawa on the ground weaving the small g. For an artist who said in 2002 that she was not modern any more because she knew nothing about technology, the Google doodle is an uncanny tribute, but one that will hopefully help enlighten new fans to the work of an artist whose grasp of nature offers inspiration when we need it most.

Surviving Ignorance

Born in 1926 in a small farming town California, Asawa was just a teenager when she became one of 120,000 Japanese Americans arrested and forcefully sent to internment camps when the United States entered World War II. She was imprisoned with five of her six siblings and her mother. Her younger sister, who happened to be visiting Japan when the rest of the family was taken into custody, was forced to stay in Japan by herself. Her father, meanwhile—a 60-year old farmer—was arrested by the FBI and imprisoned in a different camp, where he remained separated from his family for two years. Miraculously, however, Asawa held no resentment later in life for the hardships that this experience inflicted upon her. She even credits the experience with changing her life, since it was in the internment camp that she dedicated herself to becoming an artist.

Ruth Asawa - Untitled (S.069/90), 1990. Sculpture, copper wire. 30.5 × 34.3 × 33.0 cm (12.0 × 13.5 × 13.0 in). Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Her constructive outlook towards this difficult experience extends to her outlook on the entire war. After leaving the camp, she attended the Milwaukee State Teachers College, but was not allowed to teach in the public schools because of her Japanese heritage. That racism drove her to enroll in the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Black Mountain College was where many of the Bauhaus teachers fled to after being chased out of Germany by the Nazis. Asawa trained there for three years, working with the brightest minds in art, architecture, dance, and music, in what has been described as an artistic utopia. Asawa was quick to point out, though, that without the scourge of the Nazis, such a school never would have existed in the United States. It was only because these teachers were expelled from their homeland that they were willing to work for almost no pay, farming the land and cooking their own meals. As with her own experience in the internment camps, she saw Black Mountain College as an example of the amazing things that can come from making the best of every opportunity in life, even the painful ones.

Ruth Asawa - Untitled (S.454/50), 1957. Sculpture, copper wire. 40.6 × 47.0 × 43.2 cm (16.0 × 18.5 × 17.0 in). Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

The Fountain Lady

Her constructive outlook on life made Asawa an exceptional artist, because she understood the necessity of art being of value to humanity. “Activism is wasteful,” she said. “It is better to be working on an idea and building on that than breaking down and protesting something that exists.” One of the most impactful ways she found to be constructive with her work was to create public art. In her adoptive home base of San Francisco, she was known as “The Fountain Lady,” because of the many fountains she created all around the city. Perhaps her most famous is the mermaid fountain that sits in Ghirardelli Square, in front of the iconic Ghirardelli Chocolate Company. The fountain for which locals love Asawa the most, however, is simply called San Francisco Fountain, and it epitomizes her commitment to constructive aesthetics.

Ruth Asawa- Detail of San Francisco fountain in Union Square.

The fountain is built into an unassuming stairway leading to a small pocket park near Union Square. To make it, Asawa worked with children from all of the city, inviting them to create clay models depicting their favorite aspects of San Francisco. After the children made the models, Asawa had the clay forms cast in bronze to form the low-relief exterior of the fountain. Said Asawa, “When I work on big projects, such as a fountain, I like to include people who haven’t yet developed their creative side — people yearning to let their creativity out.” The San Francisco Fountain is something anyone might happen across. It is easily understood, and speaks to the fact that we are all in this together. Though it is nothing like the work for which Asawa is best known, it is perhaps the most perfect expression of her art: it is a direct, hopeful aesthetic expression, one guided not by academic theory, but by an understanding of our nature—that we are all in this together.

Featured image: Ruth Asawa - Untitled (S.383, Wall-Mounted Tied Wire, Open-Center, Six-Pointed Star, with Six Branches), 1967. Hanging sculpture—bronze wire. 46 x 46 x 6 inches (116.8 x 116.8 x 15.2 cm). Showcased at the David Zwirner Gallery, 2017.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio