Sophie Taeuber-Arp - A Major Female Force of Dadaism and Concrete art

Jun 24, 2021

Bold and dynamic, Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943), née Taeuber, was a major female force in the European avant-garde movements of Dadaism and Concrete art. Her career spanned two world wars and ushered in a new era of design and workmanship. In pursuit of opportunities and acceptance for her craft, she pushed against the limited artistic roles of women and brought applied art into the mainstream alongside fine art. Some have described her as radical, although she allegedly hated the word. I find her inspirational. Born into a large Prussian family, she had an early proclivity towards art and performance. She attended the School of Applied Arts in St. Gallen, Switzerland from 1908 to 1910, and then moved to Germany in 1911 to take courses at the School of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg and Walter von Debschitz’s studio in Munich. At the time, strict rules dictated what women could study — Taeuber-Arp was allowed to work on textiles, beading and weaving, skills that were typically considered ‘women’s work.’ She soon found that these applied arts, unlike fine art, were more accepting of abstraction. Through textiles, Taeuber-Arp could experiment with colors and shapes verging on avant-garde and still achieve commercial success with more ease than her fine art counterparts.

A Multi-Disciplinary Artist

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Taeuber-Arp returned to Switzerland and began a career in applied arts, supplementing her work by studying modern dance and exploring non-representational painting and sculpture. The neutral country had become a haven for young artists escaping the upheaval in Europe and looking for creative freedom to express the devastation of war. Taeuber-Arp soon developed a new circle of avant-garde friends in Zurich including the French-German poet and painter Jean (also known as Hans) Arp, whom she would later marry. In addition to teaching Textiles at the Zurich School of Art and Crafts, Taeuber-Arp danced at the Cabaret Voltaire, a nightclub and meeting spot for artists and poets who would form the Dadaist movement. She also designed costumes and set pieces for performances, and crafted marionettes for a production of King Stag. Through these projects, Taeuber-Arp began honing her style of simplified forms, geometric patterns and bursts of color. In 1920, she produced some of her most notable works, now emblematic of Dadaism — a series of wooden heads (like the utilitarian objects used to display hats) that were decorated and painted with abstracted faces, aptly titled Dada Heads or Tête Dada.

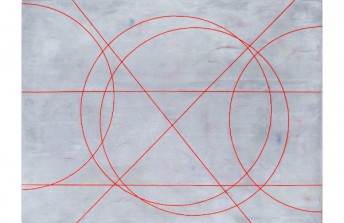

Detail of Sophie Taeuber-Arp work included in the Women in Abstraction exhibition at Centre Pompidou, 2021.

Dadaism & Constructivism

While a major player in the burgeoning Dada movement, Taeuber-Arp frequently used false names and wore masks whenever she danced. This helped show off the elaborate modern dance costumes, some of which she may have designed; it also allowed Taeuber-Arp to keep her identity a secret from her colleagues at the Zurich School, who discouraged students and faculty from participating in the avant-garde. However, Taeuber-Arp cleverly bridged both worlds, working as a teacher and textile designer by day and performing as a modern dancer and avant-garde leader at night. The decorated pillowcases and beaded bags that she produced and sold were so popular that she hired help to keep up with the demand. She also used her position with the Zurich School to advocate for the applied arts. These skills had often been deemed lesser than fine art, and through her work she promoted the discipline as an art form in its own right.

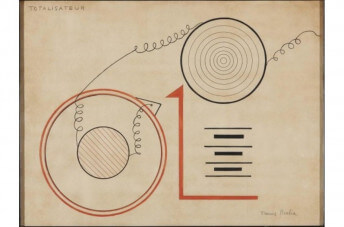

As Dadaism gained popularity and recognition, Taeuber-Arp found herself at odds with the increasing absurdity and significance taking hold of the movement. She wrote to Jean Arp in 1919, “I’m furious. What is this nonsense, ‘radical artist.’ It must only be the work, to manifest oneself this way is more than stupid.” Her work of this period began to take on more Constructivist tones, an austere abstract movement sweeping through Russia that emphasized technical mastery and materials that reflected industry and urbanization. In 1922, she and Arp married and collaborated on several projects, including working with designer Theo van Doesburg on the now-famous interior of Cafe de l’Aubette in Strasbourg, France. It was one of the first instances where abstraction and architecture were brought together in a space. Moving to Paris in 1929 brought the couple into a new circle of artists who were exploring non-figurative art including Joan Miro, Wassily Kandinsky and Marcel Duchamp. During this time, she was a member of several abstract and avant-garde arts groups and edited the Constructivist art magazine Plastique. Like earlier Russian avant-garde artists like Kazimir Malevich, she frequently featured circles and was one of the first artists to use polka dots in fine art.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp work included in the Women in Abstraction exhibition at Centre Pompidou, 2021.

Later Years & Legacy

In 1940, Taeuber-Arp and her husband moved to the south of France and then fled to Switzerland in 1942 to escape Nazi occupation. Shortly after, while staying at the home of Swiss designed Max Bill in 1943, Taeuber-Arp tragically died from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a faulty stove. She and Arp had been hoping to get visas to travel to the United States. Arp remarried in 1959; however, he spent his later life promoting Taeuber-Arp’s work as she remained largely under-represented in the history of Dadaism and European avant-garde. Her art and life have also been cited as an inspiration for the Feminist Art movement in the 1960s, which correctly identified Taeuber-Arp as a trailblazer. In the 1980s, the Museum of Modern Art in New York undertook the first traveling Taeuber-Arp retrospective to recognize her contributions to geometric abstraction and concrete art, and brought her vision to cities around North America. In 1995, the Swiss government added her portrait to their 50 Swiss franc note, making her the first woman to receive this honor. While her name today is still less familiar to many than that of her husband, Arp, or her contemporaries, she is now regarded as one of the most important artists of the 20th century.

In 2021/2022, her work will be the subject of a major traveling retrospective entitled “Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction” exhibited at the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland, the Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Featured image: Sophie Taeuber-Arp work included in the Women in Abstraction exhibition at Centre Pompidou, 2021.

By Emelia Lehmann