A World of Beauty, Science and Visual Delights-Takis On Tour

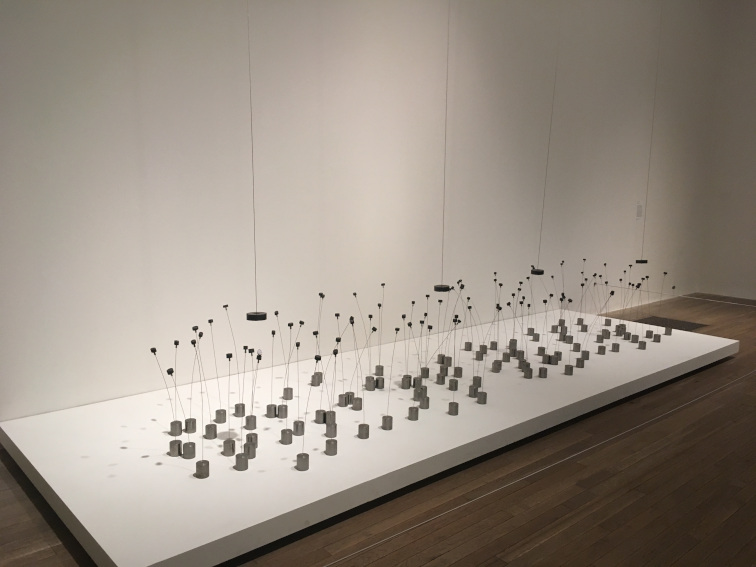

It is rare that an art exhibition gives me chills, yet it happened numerous times as I toured Takis: Sculptor of Magnetism, Light and Sound at the Tate Modern. Knowing little about the artist before entering the exhibition, except that he was known for using magnets in his work, I had few expectations going in. My openness was rewarded with a cavalcade of tiny miracles, as each of the more than 70 works on view drew me deeper into the mind and methods of a truly extraordinary artist. Magnetism, it turns out, is only the beginning of his method. Takis mobilizes a whole range of other earth energies as well, including electricity, light, gravity, momentum and sound. His objective with each work seems to have been to set up a kinetic—or potentially kinetic—composition in space, like a visual vignette designed to simultaneously demonstrate aesthetic appeal and scientific inevitability. As Takis expressed in one of the many poetic statements scattered throughout the exhibition, “We try to achieve spiritual collaboration between artist and scientist.” The first such collaboration I witnessed after entering the exhibition was an arrangement of what looked like flowers growing out of a long white plinth on the floor. The flowers swayed gently, as if moved by a breeze. Upon closer examination I realized the flowers were thin strips of metal being activated by magnets suspended from the ceiling. As the magnets swung, the metal flowers reacted; meanwhile other invisible forces, like momentum, gravity, heat from the lights and wind from passing viewers also exerted their tiny influences. At least a dozen people, I included, stood enraptured by this statement of subtlety and profundity—a perfect introduction to the blend of science, beauty and visual delights that awaited in the galleries to come.

Nailed It

Takis was born Panayiotis Vassilakis in 1925 in Athens, Greece. An auto didact, he began his self-training with primitive figurative studies in traditional materials like plaster and metal (some of which are on view in this exhibition). In 1954, after moving to Paris, he became immersed in the international avant-garde. He soon completely abandoned figurative art in exchange for something more radical: a search for ways to make art that harnessed the phenomena of nature. The first series that introduced Takis to the creative circles of 1960s Europe and America were his magnetic sculptures, which cause nails and other metal objects to hover in space. Perhaps the simplest such work is “Magnetron” (1964), a U-shaped magnet that exerts its pull on a single steel nail attached to a string. The nail floats, defying gravity: a perfect, silent statement of the beauty and power of the natural world.

Takis - Magnetic Fields, 1969, Installation view

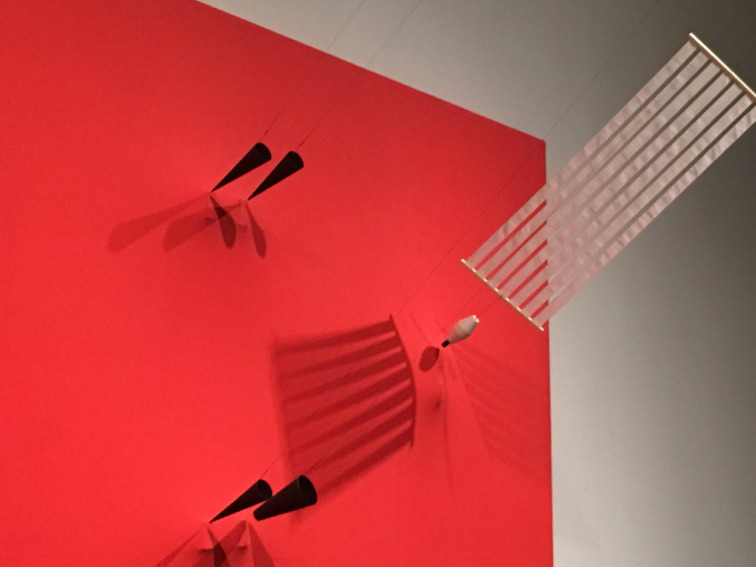

More elaborate, yet equally simple, are the series of paintings Takis made that also employ magnets. Each starts with a monochrome painted canvas. Magnets can be seen bulging outward from behind the surface of the canvas. Supports protrude out, and strings attached to the supports connect to an assortment of metal forms, such as cones and planes. The forms are pulled towards the surface of the painting by the magnets, creating an abstract composition in three-dimensional space evocative of the early abstract works of abstract artists like Kazimir Malevich or Wassily Kandinsky. Since these works inhabit both painterly and sculptural ground, Takis titled them “Magnetic Walls.” The two “Magnetic Walls” on view in the Tate exhibition not only make metal forms hover in air—their magnificent elegance made my arm hairs stand on end.

Takis - Magnetic Wall 9 (red), 1961, detail. Acrylic paint on canvas, copper wire, foam, magnets, paint, plastic, steel, synthetic cloth.

Bang a Gong

Evident throughout the exhibition is the admiration Takis had for artificial light and sound as examples of the techno-aesthetic collaboration between humanity and nature. Inspired by such common urban sights as radio towers and streetlamps, he created a wide array of light and sound sculptures. Some seemingly mimic control panels from a bad science fiction movie; others, especially his body of works called “Signals,” resemble robotic willows, swaying in the electrified darkness; still others are set to timers, coming to life only occasionally with their minor spectacles of flashing lights and vibrating wires. One of the most mesmerizing of the light and sound sculptures on view in this exhibition is “Musicals” (1985-2004), an installation of nine tall, white boards, each fitted with a horizontal metal string and a dangling perpendicular metal rod. Every five minutes the metal rods are set in motion by a motor, so they tap the metal strings and transform the room into a sort of room-sized, nine-string sitar.

Takis - Musicals, 1985-2004, Installation view

The magnum opus of the Tate exhibition, and perhaps of the entire career of the artist, is a massive installation in the back gallery, which incorporates almost every other element in the show. A jungle of “Signals” fills the gallery, drawing viewers inward towards an assortment of forms called “Music of the Spheres.” Two giant hanging orbs flank a wall-mounted gong. A metal rod hangs in front of the gong awaiting activation. An amplifier sits on the floor next to an orbs titled “Musical Sphere” since it drags itself across musical strings when activated. Every 15 minutes the piece springs to life, causing the gong and the “Musical Sphere” to ring out and the other orb to spin in electromagnetic bliss. The association with something meditative when this occurs—church bells, perhaps, or a temple gong—is inescapable, and again my skin tingled under the influence of this secular sanctum. Particularly moving in this moment was the realization that Takis, who was himself integral to the installation of this exhibition, died shortly after it opened. What a wonderful last gift he left us—this gentle reminder of the marriage of humanity, science, nature, beauty and art.

Takis: Sculptor of Magnetism, Light and Sound closes at the Tate on 27 October 2019. Those who did not catch the exhibition in London have at least two more chances It opens at to the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona on 21 November 2019, and the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, on 20 May 2020.

Featured image: Takis - Magnetic Wall (Flying Fields), detail, 1963. Cork, cloth, magnets, metal, metal wire, polyvinyl acetate paint on canvas and wood.

Text and photos by Phillip Barcio