The Influence of Abstract Art on Modern and Contemporary Design

Abstract art designs can be found everywhere, on fashion, furniture, architecture, advertising, and just about every other product of contemporary design. Whether it’s a shoe line inspired by Op Art, champagne flutes inspired by a Dan Flavin installation, or set decoration on a hip hop video inspired by James Turrell, it’s just the latest manifestation of an ancient tendency: designers influenced by art. It’s what the Bauhaus was based on; a total art that encompassed all aesthetic phenomena. And it’s why abstract art is the foundation of so much design in the culture today.

Abstract Art and Design Rebuilt the World

After World War II, humanity needed designers on a scale more grand than ever before. Much of Europe, Asia and the Mediterranean were in need of rebuilding after being bombed virtually to rubble. And it wasn’t just the buildings and city streets that needed help. A human populace devastated by years of depression, famine and war needed new everything: housing, clothes, transportation, tools, furniture, public gathering spaces, telecommunications devices, and on and on.

The world’s industrialization capacity was at an all time high thanks to mobilization for the war, and society’s applied artists found unprecedented opportunities to redesign what would become the new world, and help bring culture back from the brink. Applied artists like architects, furniture designers, fashion designers, automobile designers and industrial designers dove head first into practicality, creating products that could be mass-produced efficiently and cater to the widest possible consumer base.

Charles and Ray Eames - Case Study House No. 8

The Yin Yang Theory at Work

The prevailing abstract artists of the time were also striving to help grasp what had happened to the world. But rather than rebuilding society, which is not usually considered to be within the realm of Fine Art, they were working to contextualize it. Post-War abstract artists were trying to understand something inherent about themselves. They were confronting the unknown, the subconscious, and the deeply personal aspects of their humanity.

One way to look at it is that a balance was being struck. Designers responded to the madness of war with efficiency and logic. Abstract artists responded to it with intuition and emotion. These complimentary forces both had their effect on the consciousness of Post War society. On one hand, the Western world was becoming as contemplative and existentially profound as it had ever been. On the other hand it was becoming its most materialistic.

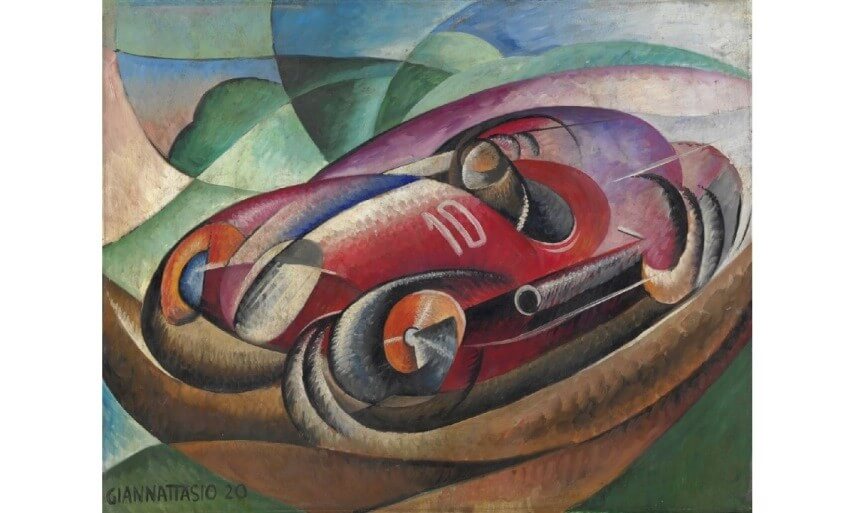

Ugo Gianattasio - Untitled, 1920

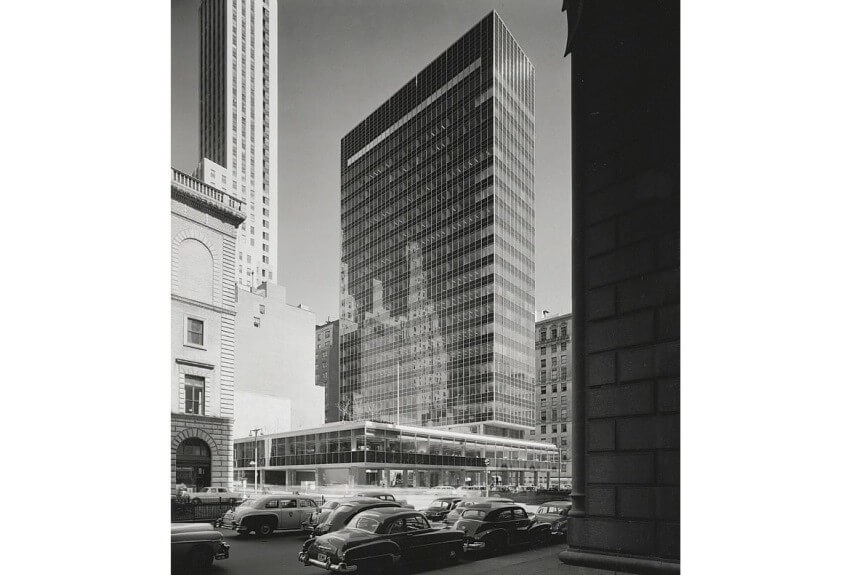

In the Post World War II era, two of the most influential designers were Charles and Ray Eames, creators of the famous Eames Chair. In 1949 they designed and built their Case Study House No. 8, which they used as a home and studio. The building was considered to represent the height of contemporary architectural design at the time. According to the Eames Foundation, the design was part of a project intended to “express man’s life in the modern world.” The house looked like a Piet Mondrian painting from about thirty years earlier. Mondrian died in 1944. In New York City in 1950, one of the crowning architectural achievements was an award-winning skyscraper known as the Lever House. Heralded as a masterwork of modern architecture, it’s clean lines, use of steel and glass, supremely functional use of space and utter lack of ornament made it a supreme example of Modernist architecture. It perfectly expressed the aesthetic concerns of 1920s Russian Constructivism.

Lever House, New York City

The biggest innovation in automobile design in 1950 was the invention of the hardtop convertible. What could make more sense? It’s the height of functionality and style, making use of cheap, new, lightweight materials and a growing consumer demand for options. And the sleek design of the cars was truly futuristic, almost exactly as futuristic as 1920s Italian Futurism.

1950 Chrysler Town & Country

Did Abstract art affect modern design? Absolutely. Piet Mondrian’s De Stijl aesthetic obviously had a profound effect on the Eames’ house, it was just decades after Neoplasticism had been introduced. The Lever House was the perfect constructivist skyscraper; it just came around a few decades after constructivist architecture had introduced itself. And hardtop convertibles were indeed the cars of the future; the 1920s future and the 1950s future.

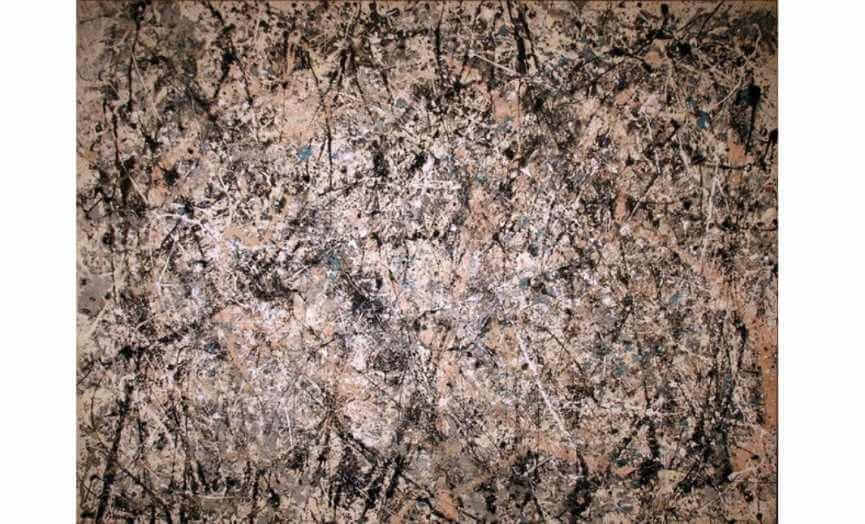

What was happening in abstract art in 1950s was this: That was the year Jackson Pollock painted “Number 1, 1950” and Franz Kline painted “The Chief.”

Jackson Pollock - Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist), 1950, oil, enamel, and aluminum on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1976.37.1

The Abstract Expressionism of Architecture

As innovations in telecommunications advanced rapidly, the speed with which abstract art was able to influence design also increased. Instead of 30 years, it only took about 10 years for Abstract Expressionism to make its mark on the world of design. The aesthetic and philosophy behind Abstract Expressionism came about through a dissemination of the entire process of art making. It was a return to intuition, to the primeval origins of subconscious influences. It was the fulfillment of Abstraction’s ultimate goal: the discovery of originality and the true expression of the essence of the unique individual.

The Abstract Expressionist philosophy manifested in architecture in the form of Deconstructivism. Deconstructivism sought to achieve an element of unpredictability. Rather than adhering to functional forms that lacked ornamentation, deconstructivist architects sought original forms that overtly utilized ornamental design elements. Many deconstructivist architects designed buildings that themselves looked deconstructed, as if fragmented into sections. Others designed buildings that mimic the gestural aesthetics of Abstract Expressionist art. Though initiated in the late 1950s, the style continues to be utilized today. Its most recognizable adherent is probably Frank Gehry.

Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao

Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao

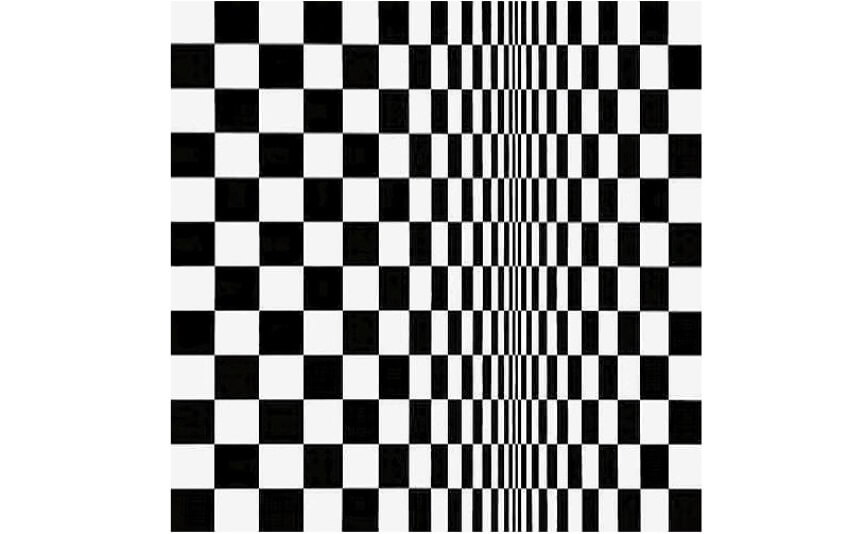

By the mid-1960s, design trends were almost immediately imitating trends in abstract art, particularly fashion design. Bridget Riley painted her seminal Op Art work, Movement in Squares, in 1961. Time magazine coined the term “Op Art” in 1964 in response to a show of Julian Stanczak's work at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York. In 1965, the style was so fully rendered in the popular culture it was referenced in a photo spread in Vogue Magazine.

Bridget Riley - Movement in Squares, 1961. Tempera on hardboard. 123.2 x 121.2cm. © 2018 Bridget Riley. Courtesy of Karsten Schubert, London

Minimal Influences

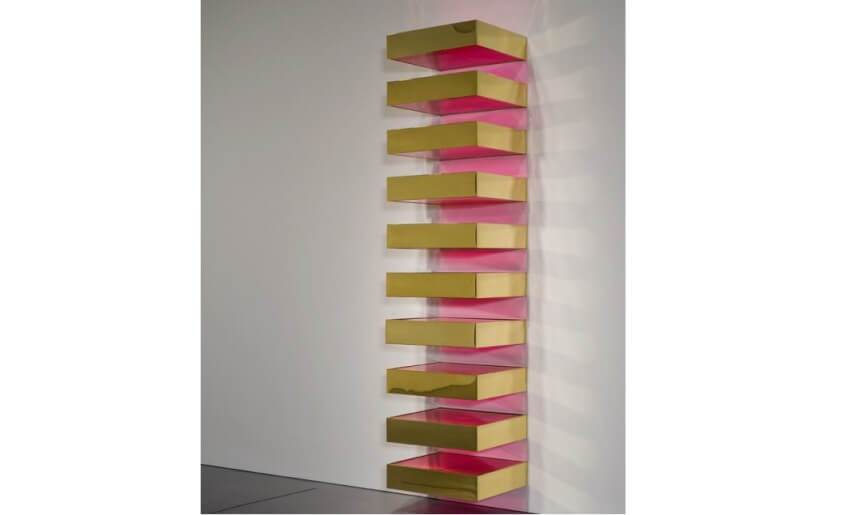

In the 1970s, one of the predominant styles of abstract art was Minimalism, and one of the most influential voices of Minimalism was an artist named Donald Judd. Judd and his contemporaries sought to make work that was fundamentally different than the works of previous abstractionists, especially the Abstract Expressionists. Minimalism eliminated personal biographical elements from the work and sought simplified forms and a pared down visual language.

What makes Judd such a fascinating study is that he was not only a minimalist artist, but he was also an architect and a furniture designer. As a proponent of both fine art and the applied arts, he was able to simultaneously manifest his concepts across the various fields in which he worked. In some ways Judd was the personification of the ideals of the Bauhaus, or of Art Nouveau, both of which stressed a simultaneous expression of all the arts working together on the same ideas.

Donald Judd - Prototype Desk, 1978. LACMA Collection. Gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee. © Museum Associates/LACMA

Judd was also an avid writer and theorist, and had this to say about the difference between the fine arts and the applied arts: “The configuration and the scale of art cannot be transposed into furniture and architecture. The intent of art is different from that of the latter, which must be functional. If a chair or a building is not functional, if it appears to be only art, it is ridiculous...” That philosophy is evident in the different work that he made.

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1971

Form vs. Function

The essential difference between abstract art and design is that abstract art, like all fine art, is something to be encountered on a contemplative level. It might be intellectual, visceral, inspirational, or aesthetically beautiful. It’s intended to get us to think, to feel, to consider, to evolve, and to wonder about the meaning of our experiences. Design’s function is quite different. It’s a way of increasing the usefulness or enjoyment of consumer products. Design must serve a function, or it is, as Judd said, absurd.

The profound influence abstract art tendencies like Abstract Expressionism, Op Art, Neoplasticism and Minimalism have had on all of the applied arts, from fashion design to furniture design to architecture and beyond, cannot be exaggerated. And happily today we live in a time when we can quickly access the history of both abstract art and design, and see for ourselves the profound effects the aesthetics and philosophy of abstract art exert on design tendencies.

Interestingly, we also live in a time when we can see those effects play out in an immediate way. An abstract painter can upload a photograph of her new painting on Instagram and seconds later a fashion designer in Milan can use that image as the inspiration for his new spring line. Or vice versa. A fashion designer can upload a picture of a new dress, and it may have a visceral effect on an abstract artist, who might then make headways into new realms of abstract art. Today everything is able to influence everything else, as our culture goes happily leapfrogging forward to meet the new.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio