Why The Irascibles Rebelled Against the Art Establishment

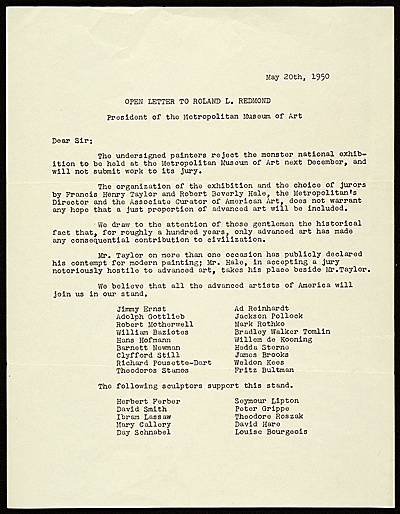

The Irascibles, or The Irascible 18, was a group of American abstract artists who signed an open letter of protest addressed to Roland L. Redmond, then President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in 1950. The letter was written in response to the announcement that Redmond was organizing a national competition to select works to be included in a monumental exhibition titled “American Painting Today.” The goal of the exhibition was to establish what type of modern painting the Met considered worthy of attention. The museum had recently ended a longstanding agreement with the Whitney Museum of American Art, under which the Whitney collected avant-garde American art and the Met collected what was considered “classical American art.” Redmond hoped this new exhibition would re-establish the Met as the authority on American Modern Art. The letter from the Irascibles complained about the jurors Redmond selected to judge which works would be in the show. Several jurors were openly biased against abstraction. One had even called abstract art “unhuman.” Adolph Gottlieb penned the protest letter, and it was co-signed by 18 other painters and 12 sculptors. It declared the signatories would boycott the competition by not submitting their work for consideration. The text positioned the signatories as progressive and the Met as behind the times, stating: “The organization of the exhibition and the choice of jurors...does not warrant any hope that a just proportion of advanced art will be included. We draw to the attention...the historical fact that, for roughly a hundred years, only advanced art has made any consequential contribution to civilization.” One signatory, Barnett Newman, had previously run for Mayor of New York and knew the city editor of the New York Times, so he was able to get the letter published on the front page of the paper. The next day, Emily Genauer, art critic for The Herald Tribune, a competing paper, published a retort defending the Met. Her article was the first to label the signatories “The Irascible 18.” To some degree, the label helped the cause of the group. Yet over time it also turned them against each other and undermined many of the ideals they held precious.

Danger in Numbers

Historians have long pondered the motivations of the “Irascibles.” Were they revolutionaries guided by ideals? Or were they just irritated because they were not making any money from their art? Or were their motivations a combination of the two? Many of the signatories of the Irascibles letter are now considered the most influential artists of their generation—such as Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, Hedda Sterne, and Louise Bourgeois. But at the time, these artists were barely making $100 a piece for their works (about $1000 today). The majority of the galleries representing them went bankrupt. There was, however, at least one Irascible who was making plenty of money from his art. Jackson Pollock had appeared on the cover of Life Magazine in 1949 in an article titled, “Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?” His follow-up exhibition sold out, netting him twice the medium family income for the time.

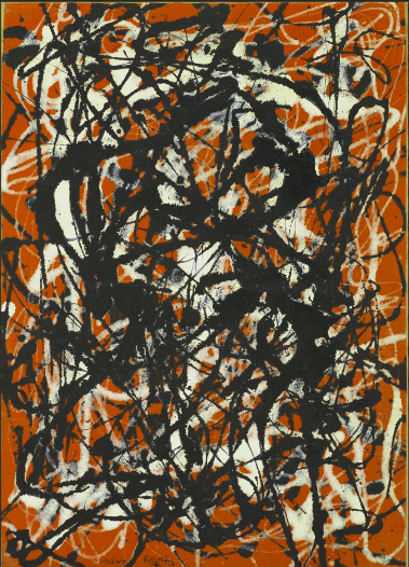

Jackson Pollock - Free Form, 1946. Oil on canvas. 19 1/4 x 14" (48.9 x 35.5 cm). The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pollock at least was not motivated to sign the letter by financial reasons. In fact, he had something to lose in that respect by adding his name. He feared the letter would cause the signatories be labeled as a “group.” Even though they all made work that could loosely be described as abstract, each had a distinctive aesthetic voice and idiosyncratic method. Pollock endorsed the letter by telegram rather than signing it, and in the end his fears came true. Life Magazine published a major article announcing the winners of the competition, and printed a group photograph of the Irascibles directly ahead of the article. The caption read: “Irascible Group of Advanced Artists Led Fight against Show.” Beneath the caption it said the Irascibles “have distrusted the museum since its director likened them to “flat-chested” pelicans “strutting upon the intellectual wastelands,” and compared their revolt to when “French painters in 1874 rebelled against their official juries and held the first impressionist exhibition.” Just like that The Irascibles were considered representatives of a movement, and the label of Abstract Expressionism—the style of their most famous member, Jackson Pollock—was mistakenly attached to them all.

Open letter to Roland L. Redmond, May 20, 1950, unsigned copy from the Hedda Sterne papers, typed, 28 x 22 cm

Undermining the Establishment

Following the publication of their group photo, many of The Irascibles grew to despise each other. Hedda Sterne never recovered from the false assumption that she was an Abstract Expressionist. The gallerist Betty Parsons meanwhile lost her biggest selling artists to more established galleries thanks to the publicity storm that followed the photograph. Lawsuits even resulted from public arguments between some members of the group. Despite these unfortunate results, however, The Irascibles did create a vital model for how artists can work to undermine the art establishment. The framed the very word “establishment” as something that implies rigidity and lack of imagination. Their revolt embodied the primal creative energy Friedrich Nietzsche described in his forward to “The Birth of Tragedy,” in which he wrote: “Here was a spirit with alien, even nameless, needs, a memory crammed with questions, experiences, secret places...something like a mystic...which stammered with difficulty...almost uncertain whether it wanted to communicate something or remain silent.”

Hedda Sterne - Rectangles, 1981. Queens Museum of Art, New York City, NY, US. © 2018 Hedda Sterne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Irascibles chose not to remain silent. They waged a Dionysian attack against the Apollonian establishment of American art. It led many of them down a dark path, but the benefits for future generations of artists are undeniable. By positioning abstraction as the advanced point of view, they stood up for originality and declared experimentation as the way of the future. The fact that the paintings of signatories like Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Still, and Robert Motherwell are now among the most expensive artworks in the world is a testament to how wrong aesthetic repression is. And the fact that the oeuvres of signatories like Bourgeois, Sterne, Gottlieb, Reinhardt, and William Baziotes have become so influential to artists today is testament to the lasting value of the instinct that guided the Irascibles to reject pessimism and fight for the importance of their work.

Featured image: Adolph Gottlieb - Lemon Yellow Ground, 1966. Lithograph in colors. 20 1/8 × 28 3/8 in; 51.1 × 72.1 cm. Edition 18/50. © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio