What is a Blue Chip Artist?

The term “Blue Chip” comes to the art world from the stock market. In 1900, after arriving in New York from England, a young man named Oliver Gingold was offered an entry-level position at the publishing firm of Dow Jones. One day, while working as a writer covering the stock exchange, he noticed several high value stocks being traded on the floor. He commented to a colleague that he was going to hurry back to the office to write about these “blue chip stocks,” the first known use of the phrase.

In standard poker sets, tradition stipulates that the blue chips have the highest value. Initially, that’s all the term Blue Chip Stocks had meant. But as time passed, and the term achieved wider use, the definition of Blue Chip evolved. It now refers not simply to a stock that’s expensive, but to the stock of companies that are reliably profitable, regardless of the general economic ups and downs.

Blue Chip… Art?

How can a work of art be a Blue Chip investment? Isn’t the value of art subjective? Yes and no. The intrinsic value of an artwork is often up for debate. Its personal value can fluctuate wildly from person to person. And its value to the artist may be impossible to quantify. When we talk about Blue Chip Art, we’re not talking about how much importance a collector or an institution, or an artist, or a history book puts on the work. We’re only talking about one thing: resale value.

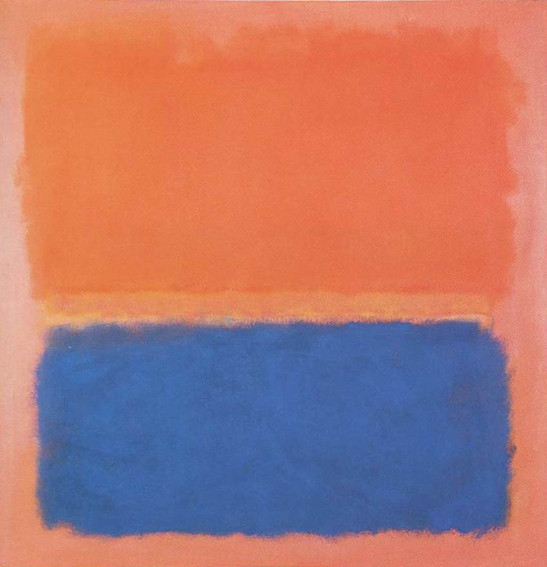

Blue Chip Art is any art that’s expected to reliably increase in economic value regardless of the general economic conditions. Artists like Picasso, Warhol, Rothko and Pollock are Blue Chip. And Blue Chip galleries tend to focus solely on reselling the work of such well-established names, artists whose works are well catalogued and authenticated, and reliably bring higher and higher prices at auction.

Andy Warhol - Marilyn Monroe, 1967. Portfolio of ten screenprints. 91.5 x 91.5 cm. Edition: 250. Gift of Mr. David Whitney. © 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All in Good Fung

How can we predict who the Blue Chip artists of the future will be? It’s a bit difficult. One reason is because art isn’t fungible. Something is fungible when one has the exact same intrinsic value as another. For example, one pound of gold is exactly as valuable as another pound of gold, so gold is fungible. But one Miro is not as valuable as another Miro. And one Miro is not as valuable as one Koons. Art is not fungible.

Fungibility makes an investment easy to understand, attracting more potential investors, and raising the possibility of Blue Chip status. Gold’s value can be understood without specialized industry knowledge. Understanding the economic value of art is less simple. Not to say fungible assets don’t lose value. They often do. It’s just that their value swings appear to be predictable, giving investors a sense of security, though it’s sometimes false.

Joan Miró - Original Abstract Lithograph from "Lithographe IV", 1981. Original lithograph on Rives vellum. Edition: 5000. 10 x 13 cm. Galerie Philia. © Joan Miró

Perception, Persuasion & Intent

Artists routinely make art nobody wants to buy. If the right critic trashes an artist’s new work, it could threaten the artist’s career. Additionally, art’s function is subjective. Whether it succeeds is therefore up for debate. There’s little chance Boeing will spend years making a plane that nobody will want to buy. And if an airplane critic calls Boeing’s new plane hideous or devoid of originality, people will still fly on it. The functionality of planes is well defined. If it performs according to expectations, it’s successful beyond debate.

The price of planes is determined by competition and demand. The market price for new art is set by agents who aren’t required to defend or even explain their valuation. To assign market value to an artist’s new work, many factors come into play, such as the artist’s pedigree and the ability of those showing and selling the work to persuade buyers there’s a demand. If the work is intrinsically appealing to a large number of buyers, legitimate demand exists. If not, demand must be manufactured by those with the ability to influence the market, for example critics, celebrities, or those with the means to buy out shows.

Mark Rothko - Blue Cloud, 1956. Oil on Canvas. 137.7 x 134.7 cm. © Mark Rothko

Who Decides?

If investing purely for financial reasons, the Blue Chip artists of the past are well documented. Simply look at the auction results from the past few decades, or focus only on buying authenticated, verifiable masterpieces from Blue Chip galleries.

At IdeelArt, we believe in collecting art not only for investment purposes, but also for art’s intrinsic value. We measure that value in many ways. We consider the work’s value to the artist, who made it with the sincere intention of producing a work of high quality. We consider its value to us, the viewers, who through the work receive an opportunity for transcendence, or aesthetic wonder. Regardless of the general economic conditions, the value of sincere intentions, aesthetic wonder and transcendent experience never declines.

Featured image: Henri Matisse - Lagoon (Le Lagon) from Jazz, 1947. One from a portfolio of twenty pochoirs. Composition (irreg.): 40.8 x 64.3 cm; sheet: 42.1 x 65 cm. Edition: 100. Gift of the artist. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

All images used for illustrative purposes only