The Utopian Architecture of Yona Friedman Reviewed at MAXXI Rome

Aug 3, 2017

Yona Friedman is part architect, part artist, part poet, part philosopher, and all human. Throughout the course of his long career, which could be said to have officially started in 1956 with the release of his Manifeste de l'Architecture Mobile, or Mobile Architecture Manifesto, the word most commonly associated with his efforts has been “Utopian.” The reference has likely been intended as an insult as often as it has been intended as a compliment. But if the users of the word would take a moment to understand its true meaning they would see that, when applied to the work of Yona Friedman, it is neither an insult or a compliment: it is simply accurate. Most of us today perceive of a Utopia as a fantasy: a ridiculously, unattainably perfect place. But that was not its original intent. Coined more than 500 years ago by the British author Sir Thomas More in his book Utopia, the word was used as the name of a fictional island where society was highly efficient, peaceful, and, in his view, highly functional. Translated from the Greek, the word literally means no place. But More used it as an allegory to describe the imagined “best state” of a republic. But it was not meant to describe perfection. On the contrary, it described possible strategies for designing a civilized society that acknowledges imperfection and accounts for it. A Utopia is not a fantasy. It is a realistic vision of a flexible place where accommodations are able to be made to maintain the peace, prosperity and happiness of its inhabitants. And although the original book by More was deeply flawed and fell far short of transforming society, Yona Friedman has embraced the idea of a flexible, accommodating, creative society and translated it into an oeuvre that has quantifiably made the world into a more Utopian place. If you have never encountered his work, it is currently on view at MAXXI, the National Museum of Art of the 21st Century, in Rome, in a major exhibition called YONA FRIEDMAN: Mobile Architecture, People’s Architecture.

The Lessons of War

Yona Friedman was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1923. As a young man he, like the rest of his generation, learned a frightening truth about human society: that it can, and often does, self-destruct. At the start of World War II, Hungary was an Axis power, allied with the Germans in war against the Soviet Union. But when the Hungarian forces began suffering heavy losses, the government sought to make a secret peace agreement with the Allies. When this back channel deal became known to Germany, the Nazis invaded Hungary. The occupying forces coerced the local population into participating in the Holocaust. It was the end of everything Friedman thought he knew about civilization. Ancient and modern structures alike were demolished, neighborhoods were razed, communities were scattered, and hundreds of thousands of his fellow citizens were turned into refugees, forced to try to survive on the run.

Friedman himself escaped the Nazi wrath by becoming a refugee. He experienced firsthand the transformation of a relatively comfortable modern, urban life into a hardscrabble life in the wild. The experience demonstrated to him the failures inherent within the systems of logic that governed modern society. He saw these failures unfold in every realm: politics, education, economics, laws and customs, religion, environmental use, distribution of resources, transportation, housing and architecture. In response to what he experienced, he began formulating a philosophy that positioned itself opposite of the ideals of the past. In short, he had observed that the status quo was to place systems, established structures and material objects higher in importance than living, creative, human individuals. So he flipped that idea, decreeing that in every aspect of society human life and freedom should be placed higher in importance than everything else.

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

The Mobile Architecture Manifesto

In 1956, Friedman introduced his philosophy to the world at the 10th International Congress of Modern Architecture, in Dubrovnik, Croatia, by way of his Mobile Architecture Manifesto. The Manifesto outlined 10 principles Friedman believed should inform new urban architecture. The principles were guided by the simple idea that inhabitants should not be forced to conform to their architectural surroundings, but rather architecture should be designed to be flexible to respond to the needs of its future inhabitants. This shift in ideals would theoretically then accomplish three things: it would allow for maximum individual freedom; it would create cities that could adapt to the changing needs of the population; and it would encourage every new generation to alter their built environments in ways that created more meaning for them.

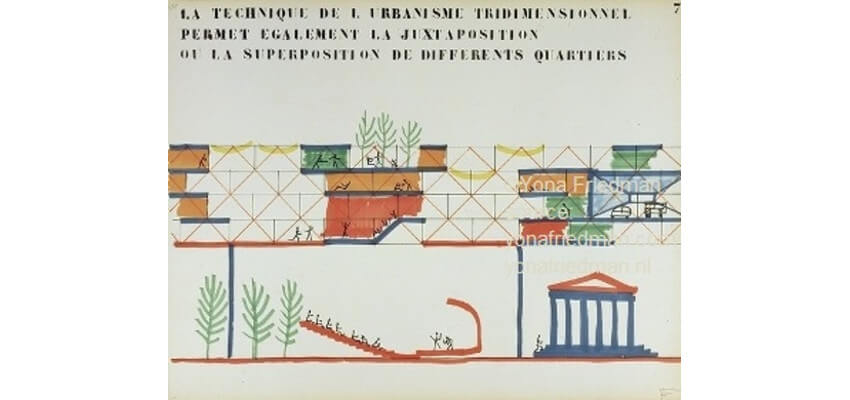

Friedman elaborated on those basic principles in future years, describing various ways they might be implemented. But rather than speaking only to academics and professionals, he went out of his way to communicate his ideas in simple, straightforward ways, such as drawing them in cartoons, insisting ordinary people should be able to understand them in order to take control of their own lives, homes, neighborhoods and cities. One of the most forward-thinking notions he developed was the Ville Spatiale, or Space City. Constructed using “three-dimensional urban planning” as he called it, Space Cities would feature modular, reconfigurable superstructures hovering a top old cities, allowing existing structures and new structures to coexist in ways that retain the old while accommodating the new.

Yona Friedman – original drawing from Ville Spatiale, 1959. Translation: “The technique of three dimensional urban planning also allows juxtaposition or superimposition of different neighborhoods.” Collection Centre Pompidou, Courtesy of Marianne Homiridis

Yona Friedman – original drawing from Ville Spatiale, 1959. Translation: “The technique of three dimensional urban planning also allows juxtaposition or superimposition of different neighborhoods.” Collection Centre Pompidou, Courtesy of Marianne Homiridis

Escaping Geometry

In addition to his fundamental belief that architecture should be flexible to accommodate its users, Yona Friedman also believed that architects had become unnecessarily bound to geometric laws. He opposed traditional geometric architecture on two different grounds. The first was the inherent lack of imagination it allowed for since predetermined, geometric spaces like squares and rectangles, which tend to come in predetermined, repetitive sizes, are limiting in their possible uses. The second was that geometric forms are not, as many people believe, necessarily the strongest bases for architecture.

As alternatives, Friedman has, over the years, put forth scores of other non-geometric approaches to architectural design. He has proposed buildings constructed from orb-like modules that can be moved around at will in order to alter the shape of the building, and which can each accommodate infinite variations on its interior spatial layout. He has also proposed structures based on crumples, squiggles, folds, swirls, cones, and numerous other random, organic designs. These structures, he has argued, are not only just as stable as the traditional, geometric matrixes on which most modern architecture is built, but in many cases they are even more solid.

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

Elevating Architecture to an Art

Of course, in addition to the academic and philosophical aspects of his work, there is also an aesthetic aspect to what Yona Friedman does, and a constructive social aspect as well. His sculptures and photomontages have been extensively exhibited, and he has made many films and created multiple works of public art. He has also devoted decades of his life to manifesting his Utopian ideals in concrete ways. He has worked with governments and NGOs to create instructional guides to be distributed to impoverished, war-torn, and refugee communities, guiding people in the simple techniques needed to construct basic architecture. And he has translated his sometimes otherwise complicated scientific and social theories into easy-to-understand comic strips and animations that are both delightful to watch and almost unbelievable in their ability to communicate big ideas simply.

Yona Friedman – Project at Portikus, Installation shot, Frankfurt am Main, 2008, photo credits Yona Friedman

Yona Friedman – Project at Portikus, Installation shot, Frankfurt am Main, 2008, photo credits Yona Friedman

The curators at MAXXI have brought all of these elements and more together in a menagerie of visual thrills. YONA FRIEDMAN: Mobile Architecture, People’s Architecture brings together examples of his animated films, photomontages, and several of his “mobile and improvised structures” (along with detailed instructions for those wanting to recreate them). And in respectful deference to his belief that museums, like all spaces, should above all else be useful to the people who use them, the exhibition also includes what Friedman calls a Street Museum: an installation featuring objects brought to the museum by citizens who felt they had something they wanted to share. Says Friedman, “My understanding of architecture is very similar to my understanding of music: anyone can build, just like anyone can sing; however, some singers are so prepared that they become artists.” As YONA FRIEDMAN: Mobile Architecture, People’s Architecture demonstrates, Friedman is astoundingly prepared. He is most definitely an artist: one who does a welcome service to all others by expanding exponentially the definition of what that word means.

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

YONA FRIEDMAN: Mobile Architecture, People’s Architecture is on view at MAXXI in Rome, Italy, through 29 October 2017.

Featured image: Yona Friedman – Mobile Architecture, People's Architecture, photo Musacchio&Ianniello, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio