How the 9th Street Art Exhibition Stepped Out of the New York Art Canons in 1951

Some people say the 9th Street Art Exhibition was a radical act of culture jamming. Others say it was an act of desperation initiated by a bunch of starving artists who had nowhere else to show their work. In truth it may have been a little bit of both. Regardless, the show is the stuff of legends. Held in 1951 in an abandoned storefront in Lower Manhattan, in a building slated to be demolished, the exhibition featured the work of around 70 artists. Almost all of the participants were virtually anonymous at the time, having been shut out by the galleries, museums, and collectors who ran the New York City scene. Their rejection stemmed largely from the fact that their work was experimental and tended to be abstract, in contradiction to the tastes of the American market. Almost all of the artists in the show were also part of a social circle revolving around “The Club,” a loose collective of avant-garde artists and intellectuals that met regularly in a building at 39 East 8th Street. A series of conversations at The Club about how to get the institution to pay some respect to their work led to the idea that if they could hold a big enough group show and generate enough buzz around town, they might be able to break through the critical haze and finally have their work, and their ideas, judged honestly and fairly by the American public. With almost no money between them, they teamed up and pooled their resources, and managed to stage a monumental exhibition, which not only earned many of them critical recognition, but that also fundamentally changed the American art world.

The Castelli Connection

Initially, the biggest concern the artists involved in the 9th Street Art Exhibition had was the question of who would hang the show. Despite their camaraderie, this group of artists had some of the biggest egos the world has ever seen. They were talented, brilliant, and fiercely competitive, and they rightfully feared that favoritism, politics, or outright corruption would cause some artists to get preferential placement in the exhibition. The exhibition space consisted of a street level space and a basement. Who would get to be upstairs, and who would go downstairs? Who would have their work in the window? These were vital questions. The one individual whom all of the artists seemed to trust was an Italian immigrant named Leo Castelli, who had a bit of experience as an art dealer in Europe, and who was also one of only a few non-artist members of The Club.

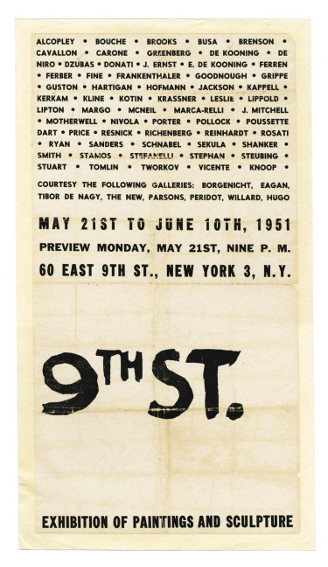

Castelli accepted the awesome task of curating the exhibition, and he also covered most of the expenses. The rent for the decrepit space for the entire length of the show was only $70. But nearly everyone involved in the show was broke, and some were literally starving. Castelli covered the bill, and the artists did all of the work to renovate the space. Franz Kline made all of the promotional materials and designed the catalogue. The buzz their preparations created spread all over New York, and the closer they got to the opening of the show, the more contentious the mood amongst the artists became. Recalling the experience years later, Castelli remarked that even though everyone was thrilled with the attention the show got, almost every single artist was dissatisfied with the way their work was presented. That means Castelli evidently did his job perfectly, since the best measure of a successful negotiation is th/blogs/magazine/abstract-expressionist-artists-you-need-to-know

Franz Kline - 9th Street Art Exhibition Poster, 1951

A Vital Link in an Important Chain

When the 9th Street Art Exhibition opened, there was a line down the street of people waiting to come in. Amongst the viewers were some of the most influential people in the New York art world—dealers, collectors, and museum directors. The works they saw in the show were created by artists who would soon become luminaries of important new art movements like Abstract Expressionism, Post-Painterly Abstraction, Pop Art, Color Field Painting, Hard Edge Abstraction, and Neo-Expressionism, styles that helped define American art in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Some of those artists received such favorable attention that they earned representation in major galleries as a result of the show, and just a few short years later several found themselves struggling with all new challenges related to sudden wealth and fame. Yet, commercial success was hardly the only legacy of this exhibition. The real reason the 9th Street Art Exhibition was so important is because of what it did to maintain a long tradition of artist-organized cultural rebellions.

The history of artist-organized counter exhibitions stretched at least as far back as 1874, when the “Anonymous Society of Painters” held its first exhibition of Impressionist art in the photography studio of the artist Nadar. It continued in 1884, when the Salon des Artistes Indépendants held its first exhibition, with the proclamation “sans jury ni récompense,” “without jury nor reward.” The 9th Street Art Exhibition continued that tradition. And all of these shows laid the groundwork for the experimental art collectives and artist run spaces that defined the late-20th Century avant-garde, and which continue to be a force for innovation today. Perhaps we now live in a time when the commercial market has replaced the government censorship and intellectual biases of the past. It does seem as if the vast majority of artists today are ignored unless they can generate huge profits for dealers, or sell tens of thousands of tickets for institutions. But this is not a reason to be discouraged. It is rather the perfect reason to look back and remember the lesson of the 9th Street Art Exhibition: that some of the most lively, engaging, and energetic art of the future is probably hiding in plain sight right now, where we least expect it to be.

Featured image: Franz Kline - Study for Ninth Street, 1951. Oil and pencil on card. 20 x 25.4 cm. (7.9 x 10 in.)

By Phillip Barcio