How Aaron Siskind Found Abstraction on the Streets

Aaron Siskind was one of the most influential photographers of his generation. In part, that influence manifested through the various teaching positions Siskind held at some of the most prestigious design schools in the United States, which included the Black Mountain College, the Chicago Institute of Design (a.k.a. the New Bauhaus), and the Rhode Island School of Design. But even prior to devoting himself to teaching, Siskind had already established himself as a pioneer in the world of abstract photography. Picking up where experimental photographers like Paul Strand, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Jaroslav Rössler left off, Siskind transformed the notion of what the medium of photography could accomplish. Rather than solely documenting the objective world, he used the medium to express the inner self, and to capture what he referred to as “the drama of objects.”

Formalities of Reality

Aaron Siskind was planning on living the life of a writer when he discovered photography, rather by accident. He received his first camera as a wedding gift in 1929, at the age of 25. But though he came to the medium late, he was instantly inspired by the potential it possessed to express emotion. In only a few years he was making a name for himself as one of the premier documentary photographers of his generation. His early talents are evident in a book of photographs to which he contributed called The Harlem Document. Created by Siskind and several other members of the New York Photo League, the book was created to communicate the nature of the lives of the impoverished urban residents of the New York neighborhood of Harlem in the 1930s.

What set Aaron Siskind apart from his collaborators on The Harlem Document was his instinct for composing a shot. He took the time to consider a variety of possible perspectives, seeking a composition that would capture not only the appearance of life but also the underlying emotion and gravitas of the human experience. Within his photographs of people and buildings one can clearly see his eye for the expressive potential of push and pull, chiaroscuro, and other formal aesthetic and design elements. About the importance of taking the time to find the perfect image, Siskind once said, “group and regroup as you shift your position. Relationships gradually emerge and sometimes assert themselves with finality. And that's your picture.”

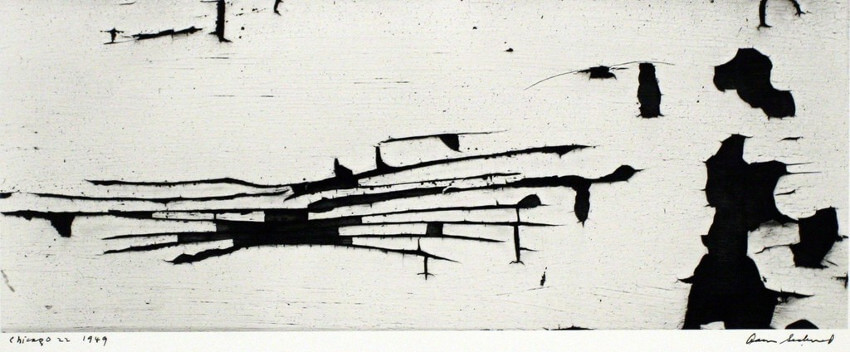

Aaron Siskind - Chicago 22, 1949, photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

Aaron Siskind - Chicago 22, 1949, photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

The Abstract Expressionist Photographer

In the early 1940s, Aaron Siskind gradually changed the focus of his photographic projects. Rather than seeking to document human society he began taking close-up photos of everyday objects and surfaces he found on the streets. His compositions were intentionally abstract. Through them he sought to convey not only the physical characteristics of his subjects but also whatever potential they had to evoke emotion. In 1945, he published a collection of these works called The Drama of Objects. The images spoke in conversation with the work of a group of painters in New York City who the following year would be given the name Abstract Expressionists. Many of them, such as Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, befriended Siskind after seeing this body of work.

In his abstract pieces, Siskind strived to include the same formal aesthetic qualities one might find in an Abstract Expressionist painting. Though flattened on a photographic surface, he nonetheless conveyed texture, depth and perspective. Though the marks were not made by his own actions, he nonetheless expressed energy and the power of physical gestures. Though he did not create the lines, shapes, rhythms and patterns in his images, he nonetheless expressed the lyricism of their relationships by harmoniously arriving at the perfect composition. And though his abstract photographs possessed undeniable content, he subverted that content by offering new interpretive possibilities based on the feelings the images conveyed.

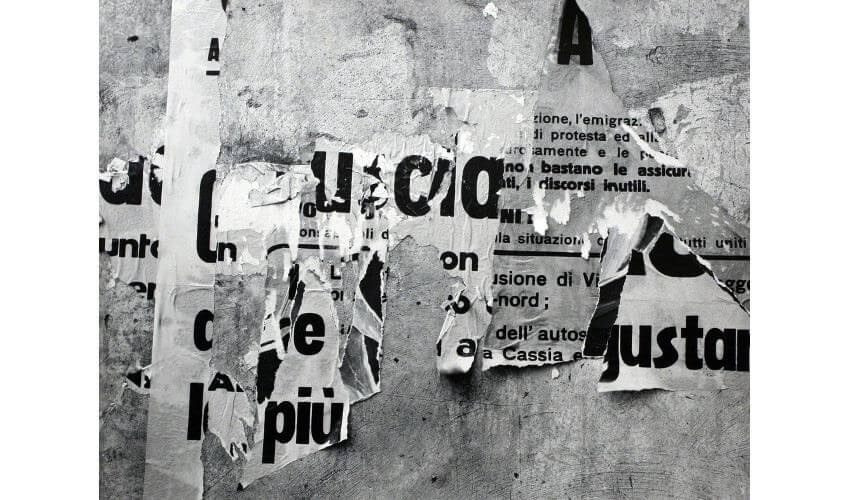

Aaron Siskind - Rome 62, 1967, photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

Aaron Siskind - Rome 62, 1967, photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

The New Documentary

Until his death in 1991 Aaron Siskind expanded his oeuvre, constantly digging deeper into the potential for photography to communicate on an abstract level. In the late 1950s, he created a series of pieces he called Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation. The series consists of high-speed photographs of shadowy human figures frozen in mid air in athletic postures set against stark white backgrounds. In the 1970s, he embarked on a new series he called Homage to Franz Kline. Siskind had been friends with the Abstract Expressionist painter Franz Kline from the early 1950s until Kline died in 1962, and he had admired the power of the iconic images for which Kline became famous. In Homage to Franz Kline, Siskind photographed real world markings such as graffiti marks in such a way that the compositions echoed the gestures Kline made, and showed similar drips and splatters.

But rather than taking something away from Kline, the photographs Aaron Siskind took of graffiti marks reveal the true depth of talent Kline possessed. Graffiti originates in passion, and demands speed and stealth. Kline achieved the same aesthetic over time, in a deliberate, careful manner. His process was exacting and laborious, not quick and dirty. The fact he was consistently able to convey the same energy, passion and grit in his studio as would be seen in a furious spray of paint on an alley wall is astonishing. Like the photographs Siskind took of human bodies in motion, the images in Homage to Franz Kline captured the sense that abstraction is hidden in plain sight within the everyday world. These photographs were not abstractions. They were documentary. They were representational. But they were a new kind of documentary. The read like modern hieroglyphs: stylized symbols combining nature and narrative; representations of abstraction that possess meaning beyond their appearance.

Aaron Siskind - Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation 32, 1965 (Left) and Aaron Siskind - Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation 63, 1962 (Right), photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

Aaron Siskind - Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation 32, 1965 (Left) and Aaron Siskind - Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation 63, 1962 (Right), photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

Featured image: Aaron Siskind - Seaweed 11 (detail), 1947, photo credits Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, © Aaron Siskind Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio