Alfonso Ossorio and his Congregations of Found Objects

Nov 30, 2018

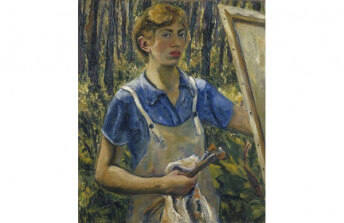

Alfonso Ossorio is almost a forgotten name today. And yet Ossorio was a key figure in the development of Post War Modernist Art. Born into a wealthy family, Ossorio was an avid art collector whose patronage sustained many artists at crucial times in their career; he was also a beloved socialite whose East Hamptons estate briefly became one of the most influential, if impromptu, art galleries in New York; Ossorio was also a talented and fascinating artist, whose sharp mind was both influenced by, and an influence on, some of the leading artistic geniuses of the 20th Century. He was a close friend and associate of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner during one of the most productive periods of their careers. He was a friend and protegee of Jean Dubuffet at the height of his research into Art Brut. Ossorio was even one of the first artists chosen for a solo exhibition by Petty Parsons when she opened her first art gallery in New York, in the Wakefield Bookshop. A few exhibitions in the past half-decade have sought to re-introduce contemporary audiences to the works of Ossorio. In 2013, The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., mounted “Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet,” an ambitious portrayal of how these three artists influenced each other. That same year Michael Rosenfeld Gallery mounted the solo survey “Alfonso Ossorio: Blood Lines, 1949–1953.” Four years later, Sotheby’s auctioned off a suite of Ossorio paintings on behalf of the Foundation the artist established when he died in 1990. These efforts at least began a conversation about who this enigmatic figure was. But they failed to answer why he was ever forgotten, and why he never truly received his due in the first place. I have sometimes wondered if his neglect had something to do with his overt religious beliefs. Ossorio championed the spiritual ideals of art. Though raised Catholic, he did not espouse any one dogmatic position. Instead, he described religion as a deeply personal and idiosyncratic thing essential to creativity. As he put it: “I feel that all serious art is a repository for the spirit.”

Unleashing the Primitive

Ossorio was born on the Island of Luzon in Manilla, in the Philippines, in 1916, the fourth of six brothers. His father was a wealthy businessman in the sugar industry. In a 1968 interview for the Smithsonian, Ossorio recalled that his interest in art began with the art he saw in the grand Catholic churches his family attended. But he described that art as “every day” stuff. His real inspiration came from the European magazines his family received, many of which contained ample arts coverage. He even remembers being punished for cutting the pictures of art out and trying to make a personal scrapbook. Eventually that passion helped him succeed as an art student at both Cambridge and Harvard. He learned to be an accomplished draughtsman, printmaker, sculptor, and figurative oil painter. Inside, however, he dreamt of connecting with something more spiritual, more experimental, and much more modern.

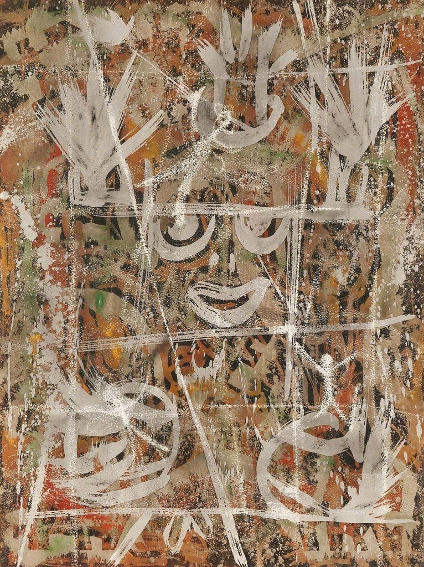

Alfonso Ossorio - Grey Prisoner, ca. 1950. Ink, wax, and watercolor on paper. 27 × 20 in; 68.6 × 50.8 cm. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

He wrote his Harvard thesis paper on “Spiritual Influences on the Visual Representation of Christ.” It explored his awareness that to create a new type of religious imagery, he knew his mind first had to evolve. A breakthrough for Ossorio came in 1948 when he saw an early show of the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock and purchased one. It was damaged during shipping so he called Pollock and asked him to fix it. Pollock invited Ossorio out to his home in East Hampton so he could repair the painting. The two became fast friends. What fascinated Ossorio was not that Pollock was forward thinking. Just the opposite. Pollock was looking back. Said Ossorio, Pollock “had bypassed the Renaissance and gone back to a much earlier period in which ideas were more important than form.” Pollock is who introduced Ossorio to Dubuffet, and Dubuffet introduced Ossorio to the Art Brut works of prisoners, children and residents of asylums that he had collected. In these examples, Ossorio found the freedom to let go of his realistic style and unleash his own primitivism, which brought him closer to the divine.

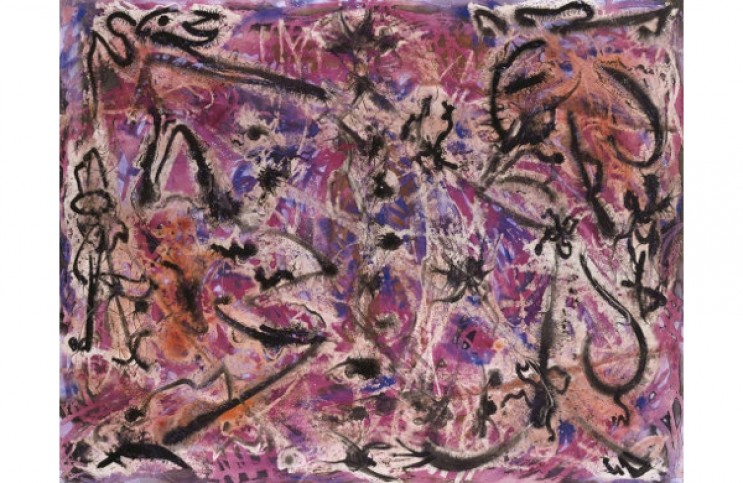

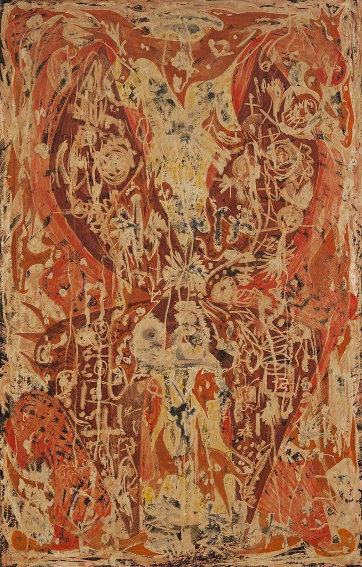

Alfonso Ossorio - #2 - 1953, 1952. Ink, wax and watercolor on paperboard. 60 × 38 in; 152.4 × 96.5 cm. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

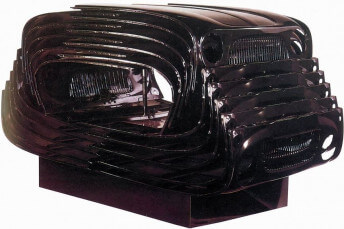

The Congregations

Primitivism first appeared in his paintings in the early 1950s. Religious symbolism blends with an intuitive, lush, all-over style of cryptic, painterly abstraction in works like “A Toi La Gloire (Thine be the Glory)” 1950 and “3 Piece Collage” (1954). Meanwhile, raw brutality, spiritualistic glow and compositional harmony come together in paintings like “Slow Dance and Staccato” (1955) and “Untitled (W55-011)” (1955). But the painting medium was not adequate for Ossorio to truly convey his feelings. He felt something was being left out. To address this void, he began inserting objects that he found, such as buttons, nails, parts of shoes and broken picture frames, into the impasto layers of paint. Soon the found objects became more important than the paint. He began using plastic to fuse the objects together, creating works that most people call assemblages, but which Osorio called “congregations.”

Alfonso Ossorio - Blue Dancer, 1962. Congregation of mixed media on panel. 26 1/4 × 21 × 1 3/4 in; 66.7 × 53.3 × 4.4 cm

Said Ossorio, “I have taken to calling them congregations simply because they all work together and the parts are unified to a final end, working for one final effect.” Yet the connection to the idea of a church congregation is unavoidable. Most contain multiple objects that look like eyes, but they are not all human eyes; they are also fish eyes, bird eyes, mouse eyes. Mixed in are actual bones. The creatures and objects that used to own these parts are dead, but they take on a second life as part of these new works of art. In some ways, these works are a beautiful homage to the time and place in which Ossorio flourished—a time when more representatives of more different cultures were converging on one city, living together and blending their ideas into a harmonious cacophony than perhaps ever before. His congregations—sanctified groupings of disparate objects brought together to begin life anew—are sublime manifestations of the respect Ossorio had for the diversity of his generation, and for the hopeful promise it contained.

Featured image: Alfonso Ossorio - Untitled, ca. 1951. Ink, wax and watercolor on paper. 19 3/4 × 25 1/2 in; 50.2 × 64.8 cm. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio