How Arman Redefined Assemblage

Jul 3, 2016

Nothing is more exciting for an art lover than to hear an artist’s story told in that artist’s own words. The tale of how young Armand Fernandez transformed himself into Arman, one of the 20th Century’s most innovative conceptual artists, was told first hand in an Arman artist interview recorded in 1968 for the Archives of American Art. In this enchanting interview, Arman relates in charming detail his life story up to that point. He recalls his pre-war youth, growing up in Nice with loving parents. His father came from privilege, was exceedingly gentle, was a “Sunday (amateur) painter” and owned an antiques store. Arman’s mother came from a poor family and wasn’t accepted by her husband’s wealthy relatives. She was strong and brilliant and focused and was a talented musician. Arman recalls nearly starving during the Nazi occupation, and talks proudly of his post-war art history and judo education. Finally he tells of the adventures that led to him becoming a founding member of Nouveau Realism, a movement that he states in the interview “lasted twenty minutes.”

Arman, Klein and Pascal Divide the World

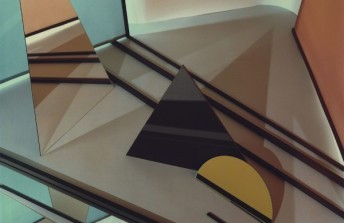

The story of how Arman became associated with the founding members of the New Realists is the story of three young friends traveling Europe together after World War II. One afternoon these three friends (Arman, the artist Yves Klein and the poet Claude Pascal) find themselves on the beach. As Arman tell it, “…we decided to become kings, but not kings to have the crown, but responsible, conscious, responsible kings...And we divided the world. Yves Klein was to take everything that was organic life…alive. Claude Pascal, everything that was natural but not alive, like stones. And me, everything that was made.”

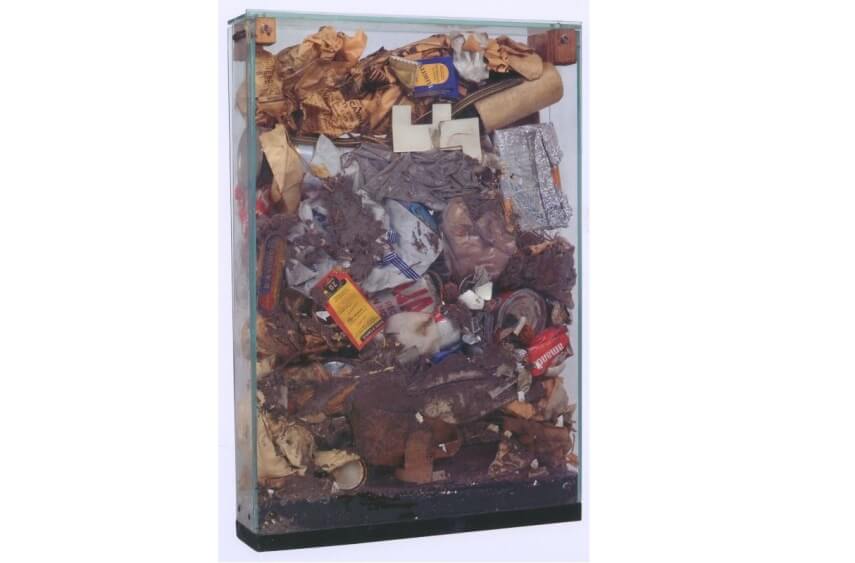

Arman - Déchéts Bourgeois (Bourgeois Garbage), 1959. © 2018 Arman Studio

For the next six decades, Arman expanded his dominion over “everything that was made” by aesthetically expressing the processes of production, consumption and destruction. He assembled massive accumulations of products, focusing on collections of like objects, found objects and garbage. He created assemblages, made prints and paintings, build sculptures and reliefs and often encase his creations in Plexiglas or concrete. He focused on exploring a repetitive visual language based on mass produced, manufactured products. The result of his prolific efforts was that by the time of his death in 2005, Arman had become the world’s most famous conceptual artists working in the technique of assemblage.

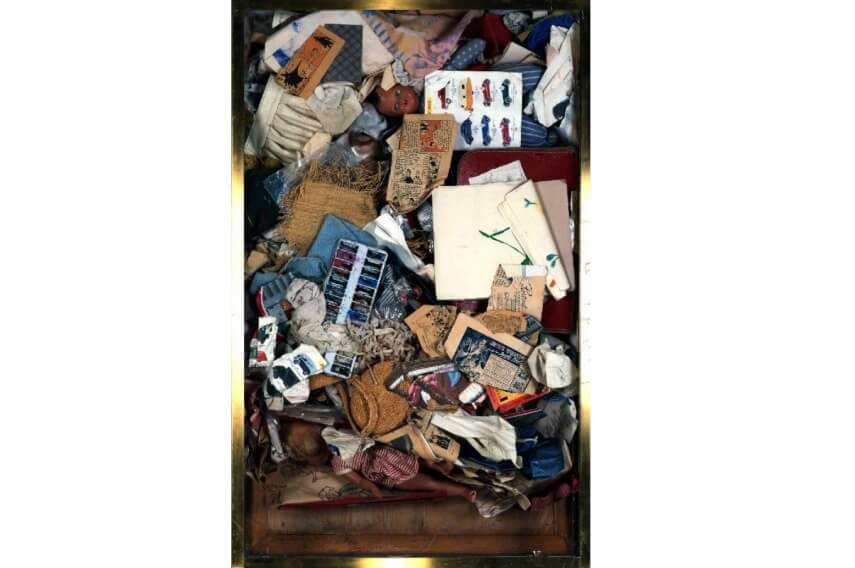

Arman - Poubelle des Enfants (Children’s Garbage), 1960. © 2018 Arman Studio

The Art of Accumulation

Throughout Arman’s career he accumulated things. He was a natural born collector. One of his earliest expressions of the act of accumulation was to collect and display accumulations of garbage. He exhibited his trash accumulations in the form of works he called Poubelles (the French word for garbage can). Some of Arman’s Poubelles were displayed in boxes made from either wood or Plexiglas. In what was perhaps his most famous, grandest and ambitious Poubelle, Arman filled the entire exhibition space of the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris with garbage. The exhibition was called “Full Up” and was a response to an exhibition staged two years earlier at the same gallery by his friend Yves Klein called “The Void,” in which the gallery was painted solid white and exhibited empty except for an empty cabinet against one wall.

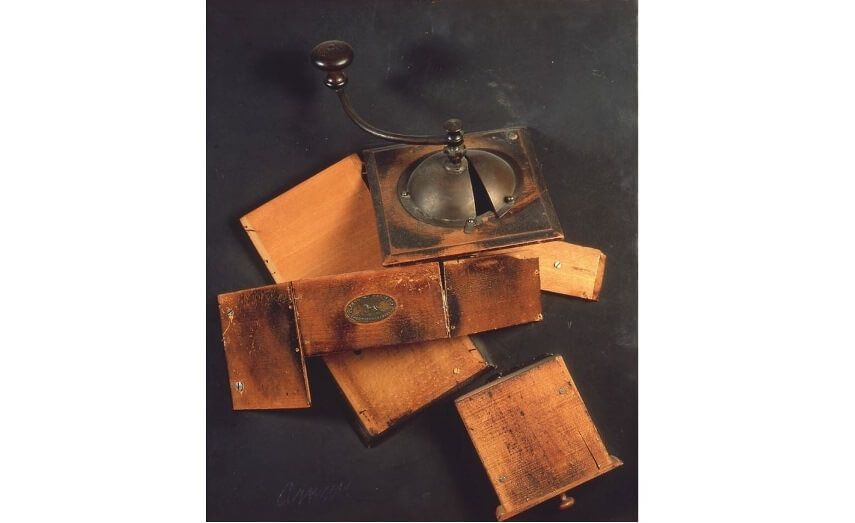

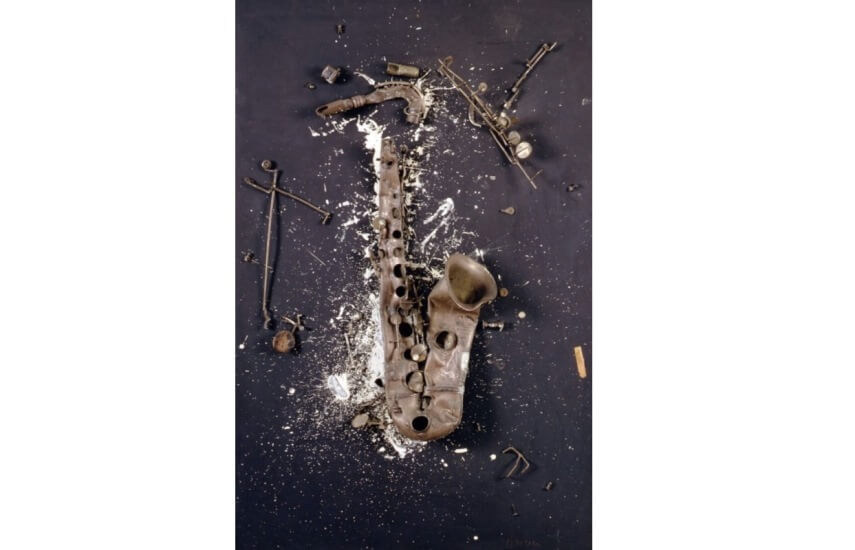

Arman’s Colères - Moulin Cubiste, 1961. © 2018 Arman Studio

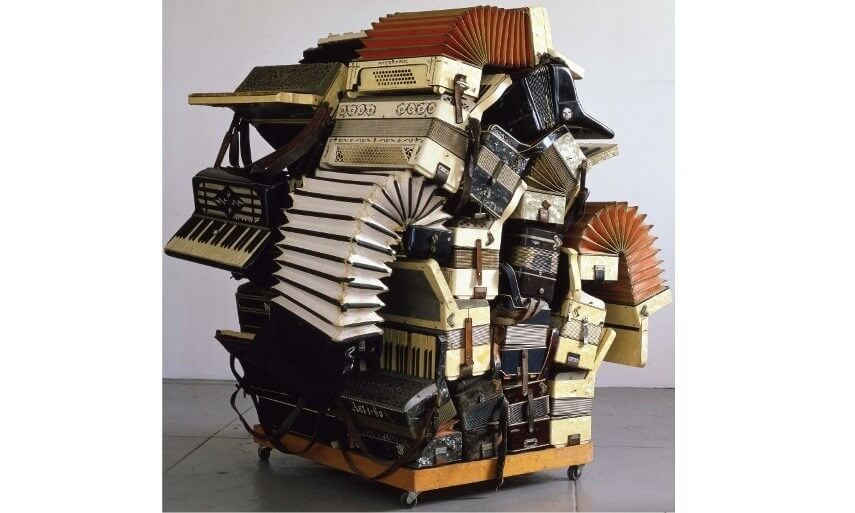

In addition to garbage, Arman collected assortments of like objects that were still useful as products. He started with simple accumulations of objects such as clothes irons, rubber stamps and tubes of paint. As with his garbage accumulations, he exhibited these accumulations encased in Plexiglas or in wooden boxes. By the 1960s he had begun to accumulate objects that possessed a more dramatic aesthetic impact, such as axes, drills, musical instruments, machine parts, car parts and clothing. When he began assembling these objects together into three-dimensional sculptural objects, he created what eventually became his signature style of assemblage.

Arman’s Colères - La Hache de Barney, 1962. © 2018 Arman Studio

A Smashing Aesthetic in the Art of Armand Fernandez

In addition to compiling his iconic accumulations and creating his signature assemblages, which examined manufactured objects from the perspective of consumption and waste, Arman also spent a great deal of time thinking about destruction. In a body of work he called Colères, Arman intentionally smashed or burned objects and then arranged their broken pieces in abstract compositions on a canvas. The word colères means anger in French, and Arman referred to these works as his “rages.” His Colères included the smashing of musical instruments such as pianos, saxophones and violins, as well as everyday objects like coffee mills, typewriters and cameras.

Arman - Cello Chairs, 1993, Cast bronze cello-shaped chairs, 33 1/2 x 16 x 19 in. © 2018 Arman Studio

Arman also explored destruction from the perspective of slicing, by cutting objects into sections. As with his smashed objects, he would often slice objects such as musical instruments apart and display them on canvases. In other instances he would slice parts of a sculpture out, for example a 1962 statuette of Joan of Arc from which he sliced large sections of her body. At times these sliced objects seemed like a philosophical riddle, trying to examine how something works by taking it apart so it doesn’t work any more. Other times, such as with his 1997 sliced assemblage The Spirit of Yamaha, they bordered on the whimsical, or possibly absurd.

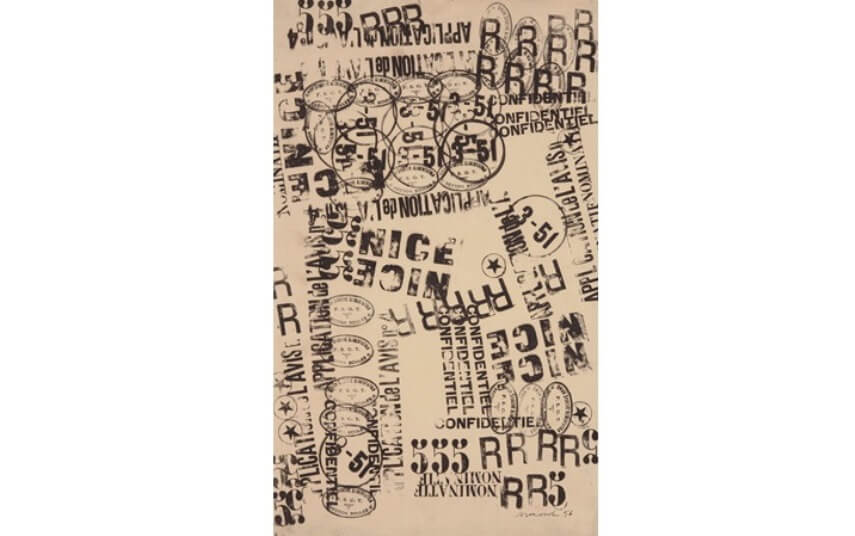

Arman - Section Bulls, 1956, Rubber stamps traces on paper attached to panel, 19.7 x 12.1 in. © 2018 Arman Studio

Arman The Producer Versus Arman The Artist

Arman wasn’t only interested in found objects and detritus. In addition to investigating the accumulation, consumption and destruction of products, Arman also spent much of his career examining the act of production. He did this through sculpture. He once made a plaster mold of his friend Yves Klein’s naked body, cast it in bronze and then painted it Yves Klein Blue . And as with the rest of his techniques, he also often returned in his sculptures to the motif of musical instruments. Sometimes his musical instrument sculptures were made in multiples, sometimes they were spliced apart and displayed in pieces, and sometimes he made them into furniture such as a table base or a chair.

Arman - Allure au Bretelle, 1958, Ink on paper mounted on canvas, 150 x 204 cm. © 2018 Arman Studio

Two Dimensional Works

Arman was also a prolific maker of two-dimensional art. Before he invented his signature style of assemblage, he began his examination of multiples with two-dimensional works. His earliest examinations of multiples came in the form of what he called Cachets and Allures. Cachets were two-dimensional works created from repetitive markings made on a surface using traditional rubber stamps. Allures were similar, but involved making abstract compositions using stamp-like impressions of ordinary objects dipped in ink.

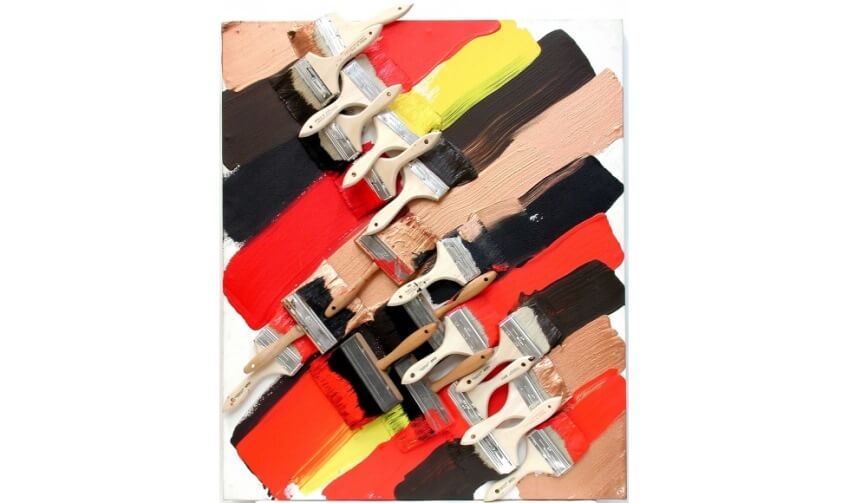

Arman - Untitled, 1994, Acrylic paint and brushes mounted to canvas. © 2018 Arman Studio

Through a body of work he called his Brush Paintings, Arman bridged the conceptual gap between his two-dimensional works and his practice of accumulation and assemblage. In these works, he used paint brushed to apply medium to a two-dimensional surface and then attached the brush to the surface. The result was a painting that contained sculptural elements of the very brushes that painted it. Though Arman made many homages and references to the Cubists throughout his career, these pieces represent a conceptual triumph in their ability to capture time and process, becoming four-dimensional in their presence, achieving something dear to the Cubists themselves.

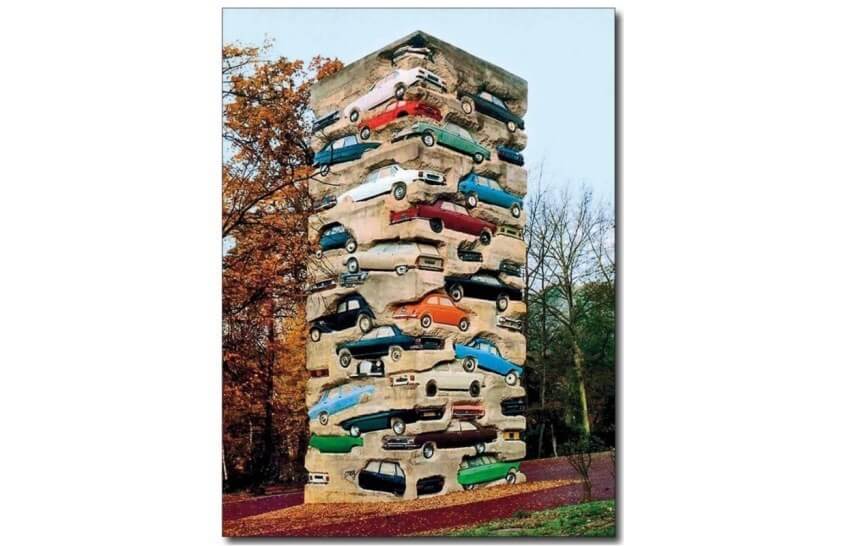

Arman - Long Term Parking, 1982. © 2018 Arman Studio

Arman - Long Term Parking, 1982. © 2018 Arman Studio

Arman’s Public Legacy

One of Arman’s most essential gifts is that of his authenticity. From a young age he was a collector and someone who appreciated manufactured objects, traits encouraged by his father’s work as an antique dealer. He was authentically a lover of music, a trait encouraged by his mother, a cellist. During the war he was on the verge of starvation for many years along with most of his neighbors. Those early influences manifested as an appreciation for the aesthetics of musical instruments, a fascination with hoarded, wasted and discarded resources, and a love for collection, conservation and preservation.

Arman - Nuits de Chine, 1976. © 2018 Arman Studio

When he came to America in the 1960s, Arman beheld a culture unlike that of post war Europe that he left behind. He witnessed mass consumption on a scale greater than the world had ever previously seen. His lasting commentary on the culture he found himself a part of is best summed up by one of his monumental public sculptures, a piece that stands 18 meters high called Long Term Parking. The work consists of 60 automobiles encased in concrete.

Arman - The Spirit of Yamaha, 1997, Sliced grand piano with Yamaha motorcycles. © 2018 Arman Studio

Though possibly ambiguous in it’s meaning, this sculpture, like many of Arman’s works, speaks to something intuitive and modern by which no contemporary human is untouched. It speaks to the very idea of assemblage: piecing disparate parts together, turning our discarded bits, our broken pieces, our rubble and our collective identity into something meaningful, and if we’re lucky, beautiful.

Featured Image: Arman - Accumulation Renault No. 106, 1967

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio