André Mare - Camouflaging the War

Feb 8, 2019

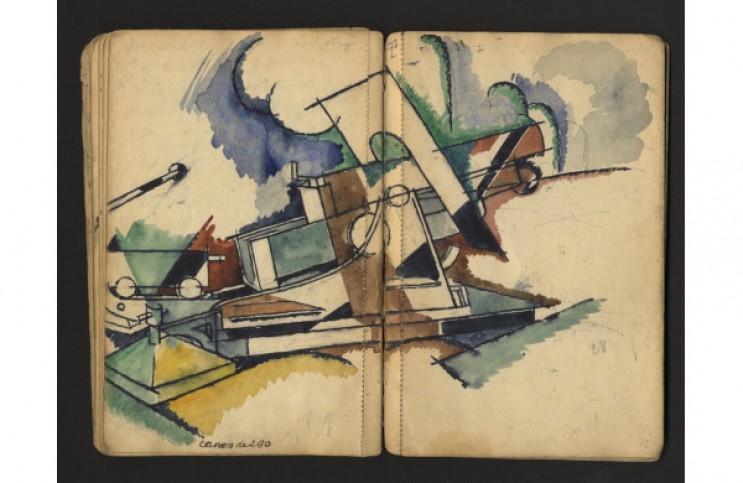

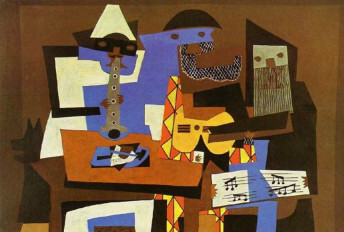

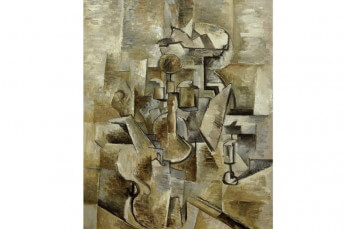

No discussion about Cubism can be complete without at least some mention of André Mare. Yet even in conversations amongst experts on the topic, it is rare that the name of this accomplished French artist and designer is brought up. Perhaps this is because Mare was admittedly not a pioneer of the Cubist method in the way that Picasso or Braque were. Nor was he necessarily a virtuoso of it, as were his friends and sometime collaborators Marcel Duchamp and Fernand Léger. Nor was Mare a top Cubist theorist, as were Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger—the authors of Du Cubisme, the Cubist manifesto. What then was the contribution Mare made to Cubist history? He was the first to apply Cubist theories to the art of war. The art of camouflage may date back to the earliest days of human civilization, but the first time it was ever officially and systematically used during wartime was in World War I. As a French army soldier, Mare was one of the first people drafted into a camouflage unit. He applied his talents broadly and successfully, leading his team in the development of a number of innovative techniques. He designed realistic looking fake trees, hollow on the inside so soldiers could climb up inside of them and use them as lookouts; he painted tanks, artillery, and the outside of tents to render them invisible from the air; and he designed and built false targets. We know about all of his ideas today because the whole time he was fighting, Mare kept a detailed diary of his experiences. Its pages show detailed, color drawings explaining how he used Cubist techniques to reduce objects in space to shapes, colors and planes in order to fool the eyes of German pilots. Just as with a Cubist painting, which strives to capture four-dimensional reality, Mare created trompe l'oeil worlds on the battlefield that captured a multitude of different perspectives all at once, so that even whilst moving, viewers could not be sure exactly what was passing before their eyes.

Artist Versus Artist

It was not unusual for Mare to have been drafted into the army. Artists have always been called upon to serve, same as any other citizen—more so in some cases, since their social status is often so much lower than that of the elites. What was extraordinary, however, was that instead of simply being stuck into the role of fighter, Mare (along with his colleague Fernand Léger, who was also part of the French camouflage unit) was given a chance to actually use his creative skills in service to the war effort. He was not asked to kill; he was asked to protect. Such specialized skills were necessary because World War I was the first war in which the battlefield was completely visible from the air. Troops and artillery cold move around in relative safety at night, but as soon as day broke they would be exposed. Mare understood the disorienting qualities of the Cubist visual language, and used that visual language to hide entire battalions and heavy artillery units, often camouflaging them in the dead of night, only to undo and then reconstruct all of his work the very next night.

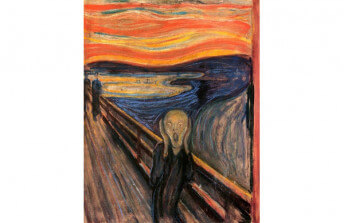

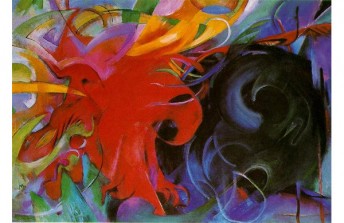

Though the French were the first to conscript artists into this special role, their enemies were quick to appropriate the camouflage strategy. A cruel irony played out as artists who only months earlier were collaborating in the progressive roll out of human culture were suddenly pitted against each other on the battlefield. Two years after Mare was drafted into the French camouflage unit, one of the most influential German artists of the time, Franz Marc, transferred into the German camouflage unit. Marc was a founder of Der Blaue Reiter, a key movement in the development of German Expressionism and Abstract Art. He was a close friend of Wassily Kandinsky, a fact that he reiterated in his own wartime diary, while describing the strange thrill of transforming the outsides of German tents into Kandinsky paintings. He wrote, “From now on, painting must make the picture that betrays our presence sufficiently blurred and distorted for the position to be unrecognizable. I am very interested to see the effect of a Kandinsky from six thousand feet.”

After the War

Despite how effective the camouflage units on both sides of World War I turned out to be, the stories of the artists involved did not usually end well. Franz Marc died when he was hit with shrapnel just months after joining the camouflage unit, never realizing that orders had already been issued to remove him from combat due to his renown as an artist. André Mare, meanwhile, survived the war, but suffered permanent lung damage from his exposure to mustard gas on the front lines. Despite his ill health, he worked tirelessly on his painting and design work after the war. He established a successful design practice along with Louis Süe, which specialized in Art Deco furniture and interiors. Examples of their textile and furniture designs reside in the collections of many influential museums.

But in 1927, Mare and Süe both left their positions at the company they had started. In addition to creative disagreements with their new partner, Mare was suffering from declining health. From that point onward, for the last five years of his life, Mare devoted himself completely to painting. Interestingly, in these later years Mare adopted a more less abstract, more figurative style of painting. He still embraced a slightly reductive style, employing large fields of pure color and Expressionistic, painterly brush strokes, but left the Cubist theories and techniques behind him on the battlefield. It is mostly in his war diary, which he published under the title Andre Mare: Carnets de guerre, 1914–1918, that his immense Cubist legacy resides. It shows how perhaps for the first time in Modern history an art movement left the studio for the battlefield, transforming nature and society in a very real and very critical way.

Featured image: André Mare - Le canon de 280 camouflé, carnet de guerre no. 2, 1915. Ink and watercolor. Fonds André Mare/Archives IMEC.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio