Clarity of Tone and Form in Barnett Newman Paintings

The iconic zip paintings of Barnett Newman, featuring thin, luminous vertical bands surrounded by immersive fields of color, are considered some of the most emotive and powerful works of the 20th Century. But Newman was not appreciated in his time. He was in his forties before he arrived at his mature style, and when he first exhibited his zip paintings critics and collectors alike universally despised them. Nonetheless, Newman remained singular focused on what he wanted to communicate with his art. His long and difficult path to success granted him a unique perspective, and an opportunity to surmise for himself the meaning and purpose of life and art. By the time history caught up with Newman, his unique perspective had resulted in an artistic oeuvre that communicates with perfect clarity the universal, the individual, and the sublime.

Barnett Newman the Writer

Barnett Newman was born with a passion for communicating, both through words and images. As a child growing up in the Bronx he once won a speaking contest in school. By the time he was a high school senior he was taking classes almost every day of the week at the Art Students League. In college he put his passions to use, studying art, majoring in philosophy and contributing articles to school publications. But despite his immense talent and drive, after college Newman found himself lacking a clear direction for exactly how to put his passions to use in a career.

After graduating with a philosophy degree in 1927, Newman started working at the family business, trying to save money before going to live the life of an artist. But when the stock market crashed two years later, nearly all prospects for him and his family were destroyed. Faced with harsh realities, Newman set out in earnest to survive any way he could. He tried substitute teaching and wrote for a number of publications on topics like politics and art history. While struggling and searching he continued painting, and made connections with other likeminded souls also struggling to find their way. Those connections included his wife Annalee, the painters Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, and the gallery owner Betty Parsons.

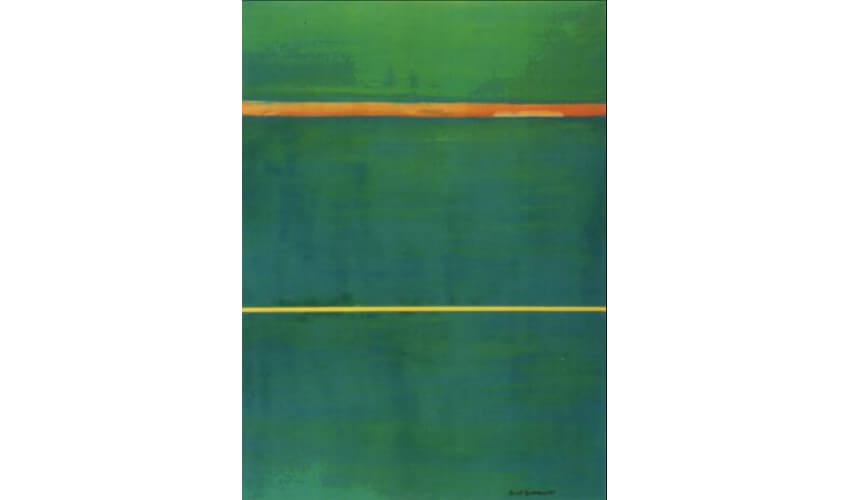

Barnett Newman - Midnight Blue, 1970. 239 x 193 cm. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - Midnight Blue, 1970. 239 x 193 cm. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman the Philosopher

Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s Newman was endlessly dissatisfied with his own efforts as a painter. He had the heart of a poet and philosopher and was seeking a way to communicate his inner nature through his art. He found solace writing about art, as he wrote exhibition catalogue essays for various other artists, thanks to his association with Betty Parsons. Those writings, along with his varied life experiences and personal struggles, led him gradually to develop a profound theory about the nature of humanity and the purpose of art.

He spelled that philosophy out in two essays he wrote in 1947 and 1948, respectively. The first essay was titled The First Man Was an Artist. In it, Newman argued that the poetic, or artistic instinct has always preceded the utilitarian instinct in humans, since the beginning of time. He argued that mud sculptures of gods had predated pottery, and that poetic grunts and screams expressive of the most primal emotions predated so-called civilized utterances. “Pottery is the product of civilization,” Newman wrote. “The artistic act is man's personal birthright.”

Barnett Newman - Dionysius, 1949. Oil on canvas. Overall: 170.2 x 124.5 cm (67 x 49 in.). Gift of Annalee Newman, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art. 1988.57.2. The National Gallery of Art Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - Dionysius, 1949. Oil on canvas. Overall: 170.2 x 124.5 cm (67 x 49 in.). Gift of Annalee Newman, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art. 1988.57.2. The National Gallery of Art Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman the Painter

The second important essay Newman wrote was titled The Sublime Is Now. In this piece he chastised all past artists for simply chasing after beauty. Even Modernist artists, he argued, were only reinterpreting what was beautiful, creating a “transfer of values instead of creating a new vision.” He asserted that he and his contemporaries were after something entirely new, “by completely denying that art has any concern with the problem of beauty and where to find it.” He asserted that the work he and they were making had no connection with anything historical, nostalgic or mythical, but was “self-evident” and made “out of our own feelings.”

The result of all of this philosophizing manifested for Newman artistically in 1948, when he created his iconic masterpiece Onement, the first of his zip paintings. The title of the piece is wordplay. It refers to the word atonement, which could mean to repair something but is also a Christian reference to the merger of humanity and divinity represented by the Christ figure. But by leaving off the first two letters of the word, Newman was also making a reference to the totality of the individual, the one, and his overarching idea that the entirety of all sublime understanding can be self-contained within one person, or for that matter, one painting.

Barnett Newman - Onement I, 1948. Oil on canvas and oil on masking tape on canvas. 27 1/4 x 16 1/4" (69.2 x 41.2 cm). Gift of Annalee Newman. 390.1992. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - Onement I, 1948. Oil on canvas and oil on masking tape on canvas. 27 1/4 x 16 1/4" (69.2 x 41.2 cm). Gift of Annalee Newman. 390.1992. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Singular Expression of Purpose

After painting Onement, Barnett Newman destroyed all of his previous works. He had achieved the aesthetic voice for which he had been searching, and from that moment onward he continued to destroy any work that did not fit his specific vision. Ironically, he was not the only person who felt the need to destroy his work. He learned that unfortunate lesson in 1950 when he began being represented by his friend Betty Parsons. Over the course of the next two years he held two solo exhibitions at her gallery. At both shows his paintings were slashed, and in their reviews critics universally derided the work.

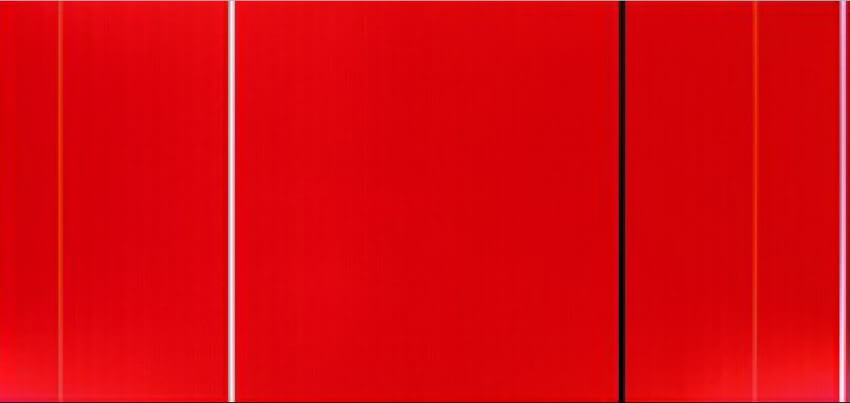

Shaken by the hate he experienced, Newman withdrew his work from Betty Parsons and completely stopped exhibiting his works for the next four years. He even bought back one of his paintings that had sold, writing to the collector, “The conditions do not yet exist . . . that can make possible a direct, innocent attitude towards an isolated piece of my work.” But he continued to paint his zip paintings, inherently believing that they communicated the purity and grandeur of the sublime, individual spirit. When he finally decided to exhibit his work again, however, it was still derided, with one critic of a 1957 exhibition of the painting Vir Heroicus Sublimis going so far as to curse about the work, and to call attention only to its size and the fact that it is red.

Barnett Newman - Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950. Oil on canvas. 7' 11 3/8" x 17' 9 1/4" (242.2 x 541.7 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Heller. 240.1969. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950. Oil on canvas. 7' 11 3/8" x 17' 9 1/4" (242.2 x 541.7 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Heller. 240.1969. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Next Generation

Despite the public misunderstanding of his efforts, Newman persisted, solidifying his expression by simplifying it. His most successful works consisted only of two elements: tone and form. The zips themselves were not so much forms as they were shapes. But the paintings were forms in their totality. The zips were really just expressions of tonal qualities, a shift in color differentiating them from their surrounding color fields. And he also expressed tone in a musical sense, as in a clear, precise, elongated expression of a voice. Through his clear expression of tone and form, Newman defined his adamant belief in the value of empowerment, idiosyncrasy, and the universal essence of the individual.

Despite his sincerity and passion, throughout the 1950s only one critic supported Barnett Newman, and that was Clement Greenberg. Though his support did little to convince the art establishment of the value of the work, it did reflect the growing understanding the younger generation had for what Barnett Newman represented. To the young painters, Rather than tying them to the past, Newman had freed them to embrace their unique individuality. He had demonstrated that viewers could approach any of his paintings and encounter them in the exact same way as they would encounter another human being: just one essential entity meeting another. He proved that paintings did not need to relate to each other, and they did not need to relate to history. He showed that every artwork was a universe within itself.

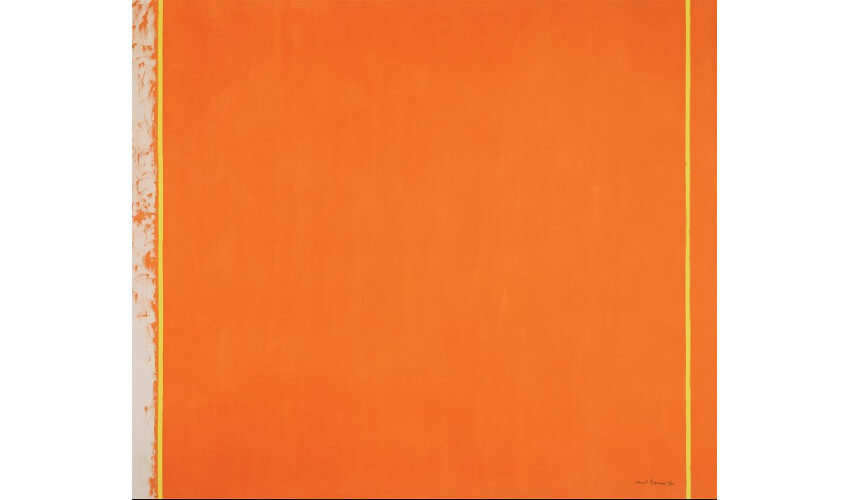

Barnett Newman - The Third, 1964. Oil on canvas. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - The Third, 1964. Oil on canvas. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Delayed But Lasting Influence

Even though it took until Newman was in his sixties before a new generation could connect with his ideas, he eventually did earn the respect and acknowledgment he deserved. Today the influence of Barnett Newman can be seen in any number of contemporary abstract artists who have created idiosyncratic aesthetic visions based on tone and form. For example consider Tom McGlynn, who has created a sublime and idiosyncratic vision based on tone and form; or the work of Richard Caldicott, which explores serial repetition and structures in the creation of uniquely singular aesthetic spaces.

Despite the initial misunderstanding towards his work, Barnett Newman is now routinely included among the best Abstract Expressionists, Color Field artists and even Minimalists. But he considered himself unaffiliated with any of those groups. He considered himself more like a movement all his own. Nonetheless, though he was not like the Abstract Expressionists in style, he was a standard bearer for the value of personal expression. Though he was not a Color Field artist, he demonstrated the ability of tonal qualities alone to create meditative and contemplative aesthetic forms. And although he was not a Minimalist, he presciently expressed the value of simplifying and reducing the visual language.

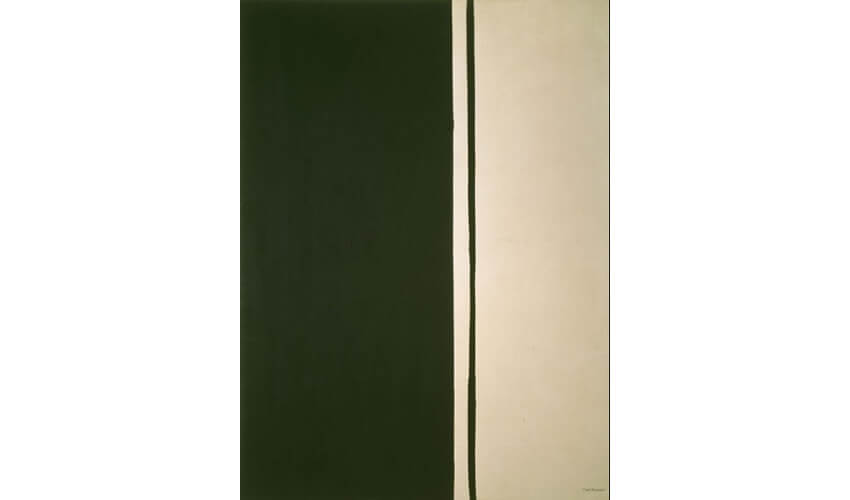

Barnett Newman - Black Fire I, 1963. Oil on canvas. 114 x 84 in. (289.5 x 213.3 cm.). © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barnett Newman - Black Fire I, 1963. Oil on canvas. 114 x 84 in. (289.5 x 213.3 cm.). © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Featured image: Barnett Newman - Onement I (detail), 1948. Oil on canvas and oil on masking tape on canvas. 27 1/4 x 16 1/4" (69.2 x 41.2 cm). Gift of Annalee Newman. 390.1992. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio