The Art and Life of Clyfford Still

In 1936, the portrait painter Worth Griffin invited Clyfford Still to join him on a summer excursion to northern Washington to paint the portraits of tribal leaders at the Colville Indian Reservation. At the time, Griffin was head of the art department at Washington State College in Pullman, near the Idaho border, and Still was a junior teacher in his department. Still agreed to accompany Griffin, and the experience was transformative for him. It turned out the Colville Tribe was in the midst of a struggle, as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had recently taken control of a large swath of their land for its Grand Coulee Dam project. The dam cut off the path of salmon swimming north up the Columbia River, and catastrophically altered the natural landscape around the river. The effect on the indigenous people was tragic. But what defined their response was not just sadness, but resilience: their focus was on life, not death. During that summer, Clyfford Still captured sensitive, intimate portraits of the Colville Tribe. He also befriended them and participated in their daily lives. He was so powerfully moved that when he returned to work at the college he helped establish an ongoing artist colony on the reservation, with the vision of offering a completely new type of experience to artists than what they were getting in the urban and university art centers of the time. Over the next three years, Still developed dueling aesthetic positions. On the reservation his work was figurative and exuberant. In his studio his paintings grew increasingly somber and abstract. By 1942, the two positions merged into a single, completely non-representational, abstract aesthetic, one that established Still as the first Abstract Expressionist. Describing his achievement, Still later said, “I never wanted color to be color. I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse together into a living spirit.”

The Thick of Things

Unlike many of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, Clyfford Still stuck to essentially the same aesthetic approach from the time he developed it, in the early 1940s, until the end of his life nearly 40 years later. Jagged, organic fields of color applied with a palette knife defined that approach. His surfaces fluctuated between thinly applied paint and thick, impasto layers. The work contained no images, per se. He never explained his paintings, and ruthlessly denied that they contained any content or objective meaning whatsoever. And he rigorously debated with critics over the power they had to manipulate viewers into perceiving his paintings a certain way. Said Still, “People should look at the work itself and determine its meaning to them.”

But, at least at first, when most people looked at the abstract paintings of Clyfford Still, they found it impossible to determine the presence of any meaning at all. What they saw was shocking compared to most other work being shown in galleries and museums at the time. The massive canvasses shrieked with vivid color, tactile layers of paint and incomprehensible forms. The pictures, if they could be called that, offered nothing to grasp onto in terms of subject matter. They seemed ominous and powerful. They conjured emotion, but confounded any attempt to understand why. And although certain visionaries like Mark Rothko and Peggy Guggenheim immediately saw the importance of the work Still was doing, almost none of the paintings from his early exhibitions sold.

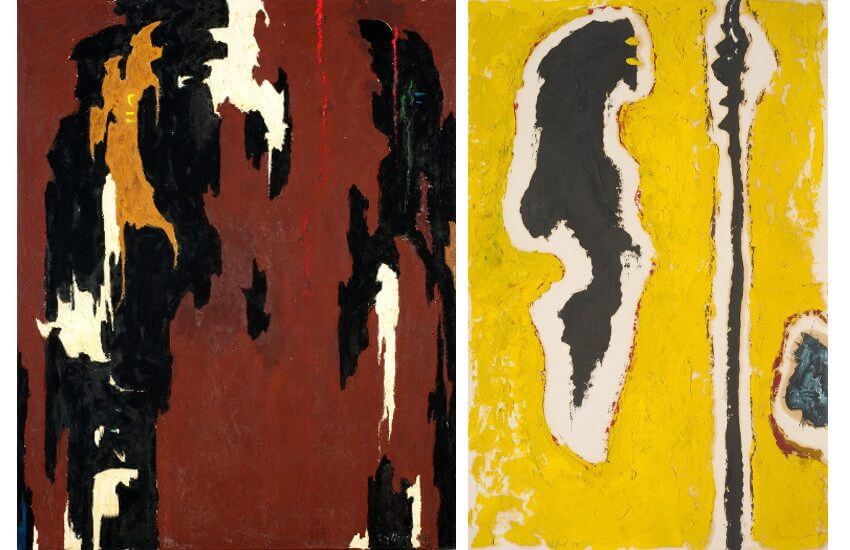

Clyfford Still - PH-945, 1946, Oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 43 inches, 135.9 x 109.2 cm (left) and Clyfford Still - PH-489, 1944, Oil on paper, 20 x 13 1/4 in. 50.8 x 33.8 cm (right). Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PH-945, 1946, Oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 43 inches, 135.9 x 109.2 cm (left) and Clyfford Still - PH-489, 1944, Oil on paper, 20 x 13 1/4 in. 50.8 x 33.8 cm (right). Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

No One Is An Island

Often today, when discussing Clyfford Still, many critics, historians, museum curators and gallery owners seem to want to recall him as a bitter, angry person, often noting that he struggled financially and usually had to work other jobs besides being an artist. Many even express outright derision toward Still. They describe what sounds like an isolated, anti-social maverick; someone who avoided making the scene and had nothing but mistrust and resentment in his heart toward the commercial art world. And certainly Clyfford Still himself admitted that some of those descriptors were accurate, at least some of the time. But Still was not entirely the angry loner he is often made out to be. He was an avid teacher, an enthusiastic supporter of other artists and an active participant in the social world of his contemporaries.

He was not even necessarily against commercial galleries or museums. Between 1946 and 1952 he showed his work in two of the most influential American art galleries at the time: Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century and the Betty Parsons Gallery. And throughout the 1950s while he was living full time in New York City, he was a fixture of the New York School scene, in both a social and a professional sense. Whatever derision he received from his haters was balanced by the adoration he received from his peers. Jackson Pollock once paid Still an immense compliment, stating, “Still makes the rest of us look academic.” And in a 1976 interview for ARTnews with the critic Thomas Albright, Still returned the compliment, saying, “Half a dozen major painters of the New York School have expressed their indebtedness to each other. They have thanked me, and I have thanked them.”

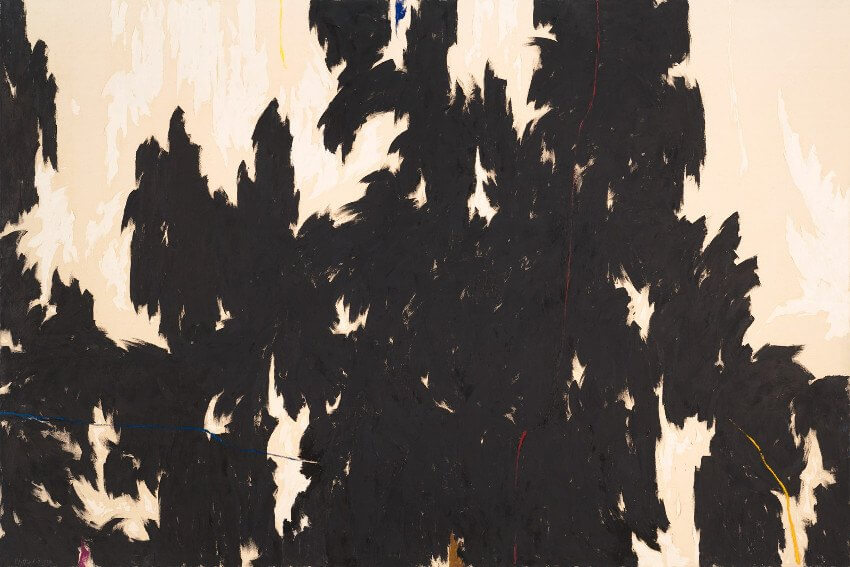

Clyfford Still - PH-389, 1963–66, Oil on canvas. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PH-389, 1963–66, Oil on canvas. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

It Is All About the Art

In reality, the only thing Still genuinely had bitterness toward was what he saw as the ethically bankrupt practices of the commercial art world, which he felt put its own business interests ahead of the art. In 1952, Still began what would become a seven-year campaign of denying all public exhibitions of his work. He felt that nothing could be gained by letting petty sales people manipulate how the public encountered his paintings. Even after he started exhibiting again he was notoriously demanding of whatever gallery, museum or publisher he worked with. None of this is to say that he was the bitter, angry person he is sometimes made out to be. Clyfford Still was simply dedicated to his art in a way altogether different than others in his generation. While Pollock was often angry and boisterous, he rarely shied from publicity. Even the famously contemplative Rothko strictly stuck to New York, rarely denying himself the attention of its wealth-and-fame-obsessed commercial art world. But Still wanted only to focus on the art.

Still simply had a different vision of the proper role of the commercial and institutional art world. Most artists feel lucky to be given a chance to exhibit their work in commercial galleries and museums, or to have it written about by critics. And most gallery owners, museum curators and art critics make a special point to remind artists how lucky they are to have such opportunities. But Still saw it the other way around. He considered that without the artists there would be no art world. He considered the art the most important thing, and he demanded that his art be supported by the art world on his terms. When any art world player refused him in the slightest, he rejected them. It was not out of anger or bitterness that he did so, but out of sincere dedication to his ideals.

Clyfford Still - PH-929, 1974, Oil on canvas. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PH-929, 1974, Oil on canvas. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Buying the Farm

In 1961, Clyfford Still left New York City forever, remarking that its commerce-frenzied, talk-filled scene was, in his opinion, beyond saving. He bought a farmhouse in Maryland with his second wife Patricia, where he lived and worked until he died. Meanwhile, he agreed to a small number of exhibitions, including a major retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1979. He also agreed to the installation of a permanent exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMoMA) following a gift he made to the institution of 28 of his works, spanning his career. As with all of the other gifts he made, Still made the museum agree to always show the works in their entirety, never to intersperse other artworks in with them, and never to separate the works from each other.

One side effect of his restrictive standards was that when Still died, he still owned roughly 95 percent of his artistic output. The public had never even had a chance to see much of his work. In 1978, when he made out his will, he bequeathed a small number of works as well as his personal archives to his wife Patricia. The rest he directed be left not to an institution or a person, but to “an American city” that would agree to build a dedicated museum to exhibit his oeuvre according to his strict standards. Those standards included that no commerce center (like a café or bookstore) be included, that no work by other artists be exhibited in the space, and that none of the works ever be separated from the collection. His work went into storage in 1980 when he died, and stayed hidden away for 31 years until Denver finally built the Clyfford Still Museum in 2011, having agreed to follow all of his demands.

Clyfford Still - PH-1034, 1973, Oil on canvas (left) and Clyfford Still - PH-1007, 1976, Oil on canvas (right). Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PH-1034, 1973, Oil on canvas (left) and Clyfford Still - PH-1007, 1976, Oil on canvas (right). Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Still A Pioneer

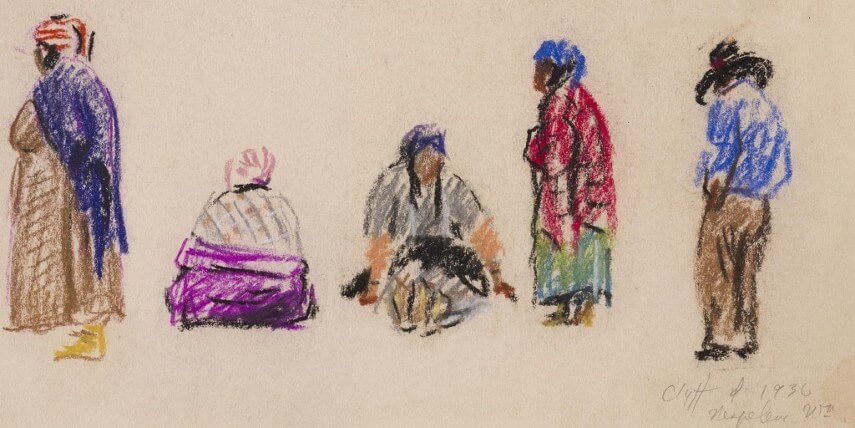

Currently, the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver possesses more than 800 Clyfford Still paintings, and more than 1500 of his works on paper, including drawings and limited edition prints. Among the works in the collection are the portraits Still created back in the 1930s while spending time on the Colville Indian Reservation in northern Washington. The pastel studies he made of the people he met on the reservation are enriched by many of the same color relationships that we find in his later abstract paintings. Those pastel drawings also convey a somber seriousness, and a deeply abiding resilience. They show stability and strength. They contain in their fleeting way every element that later defined the power and elegance of his mature work.

Clyfford Still - PP-486, 1936 (detail), Pastel on paper. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PP-486, 1936 (detail), Pastel on paper. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Aside from his epic body of work, his other gift to future generations lay somewhere in the lesson of how Still treated the official representatives of the art world, versus how he treated the people who simply came to view his art. While Still carefully selected the paintings he gave away, and tightly managed how they could be displayed, his control ended there. Every attempt to restrict institutions was simultaneously an attempt to grant freedom to viewers. He wanted us to enter into a relationship with the work on our own terms, without being told ahead of time what to think. Anyone who has ever gone on a nature walk and been told by the guide everything that one is supposed to be looking at, what it is called, what its importance is and what it means in a larger context knows the feeling of just wanting to be left alone to encounter the world for oneself. That is what Clyfford Still wanted. He created a visual universe for us to meander through. He wanted us to encounter his work in its proper environment, to experience it fused together as a living spirit, to give us the chance to discover for ourselves what we are looking at, what its importance is, and what it means.

Clyfford Still - PP-113, 1962, Pastel on paper. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Clyfford Still - PP-113, 1962, Pastel on paper. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, NY

Featured image: Clyfford Still - detail of 1957-J No. 1 (PH-142), 1957, Oil on canvas. © the Anderson Collection at Stanford University

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio