The Everlasting Legacy of Jack Whitten

Feb 1, 2018

Jack Whitten—celebrated abstract painter, social philosopher, and cultural leader—is dead at age 78. In an exhibition career that spanned more than 50 years, Whitten created an artistic legacy based on the the same principal by which he lived—that by changing our perception, we can create a more peaceful culture. In the studio, he was conceptually rigorous, aesthetically dynamic, and a tireless experimenter. Most artists are lucky to develop a single unique visual position over the course of their career. Whitten developed several. His approach was so innovative and so experimental, that it often caused him to be misunderstood, even by his supporters. That reality caused Whitten to be under-appreciated by the market for most of his life, and under-acknowledged in the art historical conversation. But the mindset of art dealers and buyers has finally started to catch up with Whitten in the past decade and a half, over the span of which his work has appeared in more than 40 exhibitions. People are coming to appreciate that despite the range of different styles Whitten employed, there are many unifying aspects to his oeuvre. For example, the idea of layers is important to everything Whitten produced. So, too, is the concept of perception. Light is also important. And so is pattern. Those four elements relate to what Whitten loosely described as his “worldview.” As he explained, “Worldview is a cosmic declaration of being.” His worldview was that light is what helps us perceive; and perception is what helps us recognize patterns; patterns are what lead us to formulate our beliefs; and our beliefs determine how we structure society. Whitten insisted that art can be a powerful agent of change, because it addresses our perception, and can thus help us create a more ethical, and empathetic world.

Art is Our Only Hope

Whitten first embraced the transformative potential of art in his early 20s. He saw it as a method of coping with what up to that point had been, for him, a horrific experience of the world. He described growing up in the American south in clear terms—non-stop racism and violence aimed toward him and every other person of color. He left his home state of Alabama in 1960, at age 21, and never returned. He moved to New York City and enrolled at Cooper Union. Fourteen years later, his works was being celebrated in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Many of the works in that exhibition belonged to what is considered his first iconic visual position—his so-called “slab” paintings. To make these works, Whitten laid his canvases on the floor and pushed paint across them with a squeegee. As soon as one layer of paint dried, he applied another, and so on. He built the layers up until the surface was dense and dimensional. Each under color shows through in the end.

Jack Whitten - Untitled, 1968, Pastel on paper, 11 3/8 × 19 3/4 in, 28.9 × 50.2 cm, photo credits Allan Stone Projects, New York

Jack Whitten - Untitled, 1968, Pastel on paper, 11 3/8 × 19 3/4 in, 28.9 × 50.2 cm, photo credits Allan Stone Projects, New York

For Whitten, these paintings were a philosophical attempt to break through to an alternative beyond his violent past. They were an attempt not so much at discovering what is universal, but rather to discover what exists beyond the self. He believed that the culture was filled with stereotypes, and that this process of working, of letting all the different colors and layers peek through to the final, abstract composition, was a way of destroying the expectations on which those stereotypes are based. His “slab” paintings are invitations to wonder what is going on; to question how something is created; to analyze pre-existing assumptions; and to think about something other than what is known. He saw them as a direct attempt to confound rigid thinking. As he once said, “Art has the power to break down barriers erected by simple-minded fundamentalist thinkers who attempt to maintain power. If fundamentalists are afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue, then Red, Black, and Green, or Pink and Lavender must give them nightmares!”

Jack Whitten - solo show at Hauser & Wirth, New York, Jan 26th – Apr 8th 2017, installation view, photo credits Hauser & Wirth, New York

Jack Whitten - solo show at Hauser & Wirth, New York, Jan 26th – Apr 8th 2017, installation view, photo credits Hauser & Wirth, New York

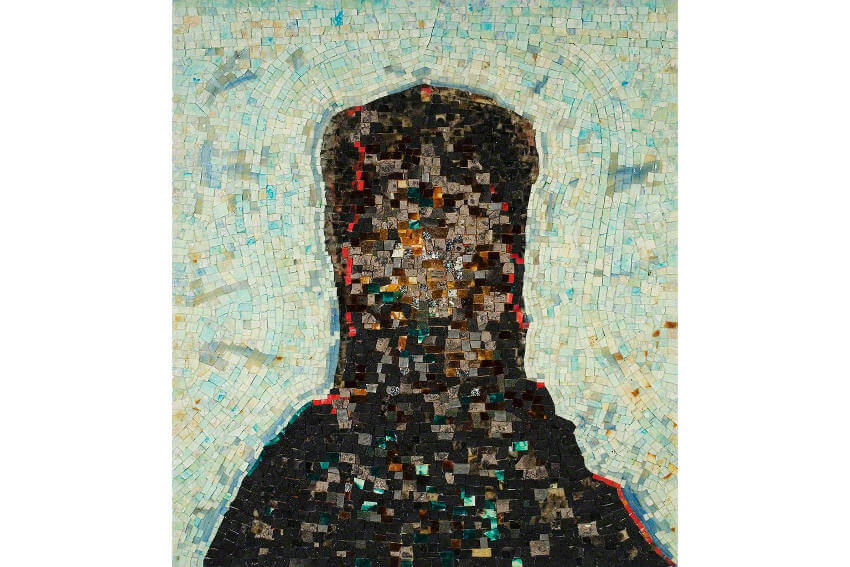

No Destination, Only Structure

As soon as Whitten became known for his “slab” paintings, he abandoned that technique and began working in a collage style, using dried up chips of acrylic paint as tiles. Using the tiles he made what look like mosaics. He realized that by not laying these paint chips flat, they reflected light differently, adding dimension and life to the works. This became his next iconic visual position. He kept developing it over the years, finally arriving at a technique of making molds for his paint tiles, rather than relying on chips of paint. He called these molded paint tiles “ready nows,” and used them to construct architectonic compositions that resemble brick walls. He used this technique to make his “memorial” paintings, such as 9-11-01, which memorialized the attacks on the World Trade Center, which he witnessed from his apartment in Tribeca. But even this technique, which proved to be the most popular with collectors and institutions, was not his final aesthetic destination. He continued to experiment and evolve for the rest of his life.

Jack Whitten - solo show at Hauser & Wirth, New York, Jan 26th – Apr 8th 2017, installation view, photo credits Hauser & Wirth, New York

Jack Whitten - solo show at Hauser & Wirth, New York, Jan 26th – Apr 8th 2017, installation view, photo credits Hauser & Wirth, New York

There exist multiple cliches to address the metaphysical question of which is more important in life: the journey or the destination. Whitten had a favorite saying, which he picked up from his former dealer Allan Stone. It went, “There is no destination.” For Whitten, life existed on a continuum—a road to nowhere. All that mattered to him were processes—processes of seeing; of thinking; of experimenting; of making. Throughout his career, he stayed true to the notion that there was always something new waiting around the bend. Like a jazz musician playing in a certain key, he gave himself underlying structures—intellectual starting points based on core philosophies. And from there, he improvised. The patterns, layers, and light he left behind for us to admire offer us paths toward new systems of perception. They show us a way forward toward something deeper and more important than self.

Jack Whitten - Black Monolith, II: Homage To Ralph Ellison The Invisible Man, 1994, Acrylic, molasses, copper, salt, coal, ash, chocolate, onion, herbs, rust, eggshell, razor blade on canvas, 58 × 52 in, 147.3 × 132.1 cm, © Jack Whitten/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jack Whitten - Black Monolith, II: Homage To Ralph Ellison The Invisible Man, 1994, Acrylic, molasses, copper, salt, coal, ash, chocolate, onion, herbs, rust, eggshell, razor blade on canvas, 58 × 52 in, 147.3 × 132.1 cm, © Jack Whitten/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Featured image: Jack Whitten - Five Decades of Painting, Target and Friedman Galleries, September 13, 2015 - January 24, 2016, Organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio