Behind Joan Snyder’s Transcending Practice

Joan Snyder has accomplished something few artists do: she has become an icon. Usually in order to be considered iconic, an artist must focus on a single style, a single technique, or a single signature method. Jackson Pollock is an icon because of his splatter paintings; Georgia O’Keeffe is an icon because of her flower paintings; Mark Rothko is an icon because of his Color Field paintings; Yves Klein is an icon because of his signature use of “IKB Blue.” The list could go on and on. What makes Snyder a perfect icon for our time, however, is that she is not known for one specific thing. She has gone out of her way not to make any one particular type of work, or employ any one particular method or technique. Since first receiving recognition for her work in the late 1960s, she has continuously evolved her practice. Every painting she makes takes on a logic of its own, defined by the past only in so far as it is informed by it. Snyder possesses an inherently likable kind of intuition, one that might pass in some circles for wisdom or enlightenment but really is more like humility. She embraces what was, accepts its influence over what is, and does not pretend to know what will be. That attitude keeps her cautiously optimistic despite the suffering she has undergone, and it keeps her paintings endlessly fresh. Viewers will never be able to anticipate what Snyder is going to do next in her studio, because she herself does not really know. Even though she plans and sketches and furiously jots down ideas, she says her paintings are actually more like jazz—“they just happen.” Snyder transcends any attempts to label her work by refusing to limit it. She remains open, honest and free. Unlike most other iconic artists, who become ensnared by some adopted truth imposed on them by history or the market, Snyder is an iconic example of an artist who knows she only has to be true to herself.

The First Maximalist

If there is one word Snyder might risk being labeled with it would be the term “Maximalist.” Born in 1940, she earned her Masters Degree in Fine Art in 1966 from Rutgers University, a couple of miles from where she grew up in Highland Park, New Jersey. The art world at that time was flirting with a small number of distinctive movements: Pop Art, Op Art, the second wave of Abstract Expressionism, Conceptual Art, Performance Art. But without a doubt the most dominant emerging trend was Minimalism. Artists like Donald Judd, Sol Le Witt and Frank Stella were stunning the eyes and minds of art enthusiasts with their pared down, unsentimental compositions. For many viewers, curators and dealers, their work seemed to be the perfect antidote to two decades of emotionally charged works by artists bent on expressing each and every one of their innermost subconscious feelings.

Joan Snyder - Can we turn our rage into poetry, 1985. Color lithograph on Rives BFK paper. 30 1/4 × 44 1/4 in; 76.8 × 112.4 cm. Edition Printersproof/20 + 1AP. Anders Wahlstedt Fine Art, New York. © Joan Snyder

Snyder saw these Minimalists and appreciated the structure and confidence of their work. But she also realized their work had nothing to do with her personally. For that matter, she did not particularly think any of those other movements had anything to do with her either. She perceived all of these art movements to have evolved out of a patriarchal art market and a skewed, incomplete, male-focused view of art history. She did not know exactly what type of paintings she wanted to make, but she knew that whatever she painted it was going to be true to herself. The first paintings she made after school were painterly explorations of the language of the grid. Next came a series of so-called “Stroke” paintings, which mapped the visual language of brush strokes. Both were attempts to build a personal syntax with which she could communicate layered, complex personal narratives. Meanwhile, the one thing she focused on above everything else was putting more and more into the work until it said what she wanted it to say. She says, “My whole idea was to have more, not less in a painting.” Her approach was dubbed “Maximalism.”

Joan Snyder - Autumn Song, 2002. Oil and mixed media on canvas. 50 × 96 in; 127 × 243.8 cm. Alexandre Gallery, New York. © Joan Snyder

A Heritage of Struggle

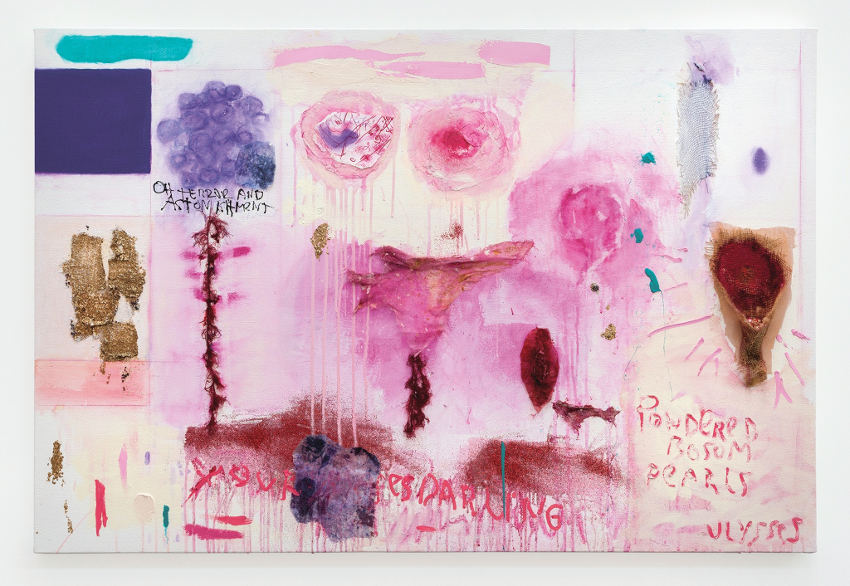

Snyder has sometimes compared her works to symphonies. Without a doubt the mixture of impasto layers, detritus, drips, and globular forms in paintings like “Amor Matris” (2015) or “Symphony VII” (2014) could be read like visual music awaiting translation by the agonized instrument of our spirits. Yet these paintings also share something in common with epic literature. Narratives play out, propelled forward by the intense darkness and light of the colors and tones. Raw, primal forms declare themselves to have character and pride; their fight to become something more presents a formidable challenge to our eyes and minds. The words Snyder introduces to paintings like “Powdered Pearls” (2017)—sometimes by writing them and sometimes by scratching them into the medium—guide our thoughts and our mood. In the end, however, the songs we hear or the stories we read in these pictures have more to do with our own internal narrative than whatever caused Snyder to put brush to surface.

Joan Snyder - Powdered Pearls, 2017. Mixed Media. Oil, acrylic, cloth, colored pencil, pastel, beads, and glitter on canvas. 137.0 × 91.5 cm. 53.9 × 36.0 in. Franklin Parrasch Gallery. © Joan Snyder

No matter how we choose to look at the paintings Snyder makes, the one undeniable thing they all have in common is their heritage of struggle. Snyder has struggled with herself to bring them into existence—a fact evidenced by their immense visual complexity and material depth. And yet they are not evidence of the type of struggle we would prefer to avoid. Instead they are evidence of an almost joyful struggle. They shine with the sort of youthful pride we carry with us at any age whenever we overcome our natural human angst. It is as though in their ambling storytelling they are trying to offer us hard to explain but undeniable solutions to problems we have always known we have, but thanks to Snyder and her efforts to be true to herself we now know we have in common.

Featured image: Joan Snyder - Small Seascape, 2011. Oil and acrylic on linen. 18 × 24 in; 45.7 × 61 cm. Alexandre Gallery, New York. © Joan Snyder

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio