Norman Lewis’s American Totem, Whitney Museum's Newest Acquisition

Feb 13, 2019

The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York recently announced its acquisition of “American Totem” (1960) by Norman Lewis, the first painting by Lewis to enter the Whitney collection. The acquisition invites new discussion about the legacy Lewis created. Lewis is frequently signaled out as “one of the only” Black Abstract Expressionist painters. In reality, however, it is unknown how many Black painters might have been trying to make a name for themselves within the Abstract Expressionist movement, since most Black artists in America at that time were either dismissed entirely, or kept on the fringe of the university, museum, and gallery systems because of their race. Nor is it even a viable argument to say Lewis himself was an Abstract Expressionist painter. He started out as a figurative artist whose paintings depicted social struggles. After he lost faith in Social Realism as a viable tool for cultural change, his style became more abstract. But even within the context of the idiosyncratic, abstract visual language he developed, Lewis retained a tight grasp of structure and a knack for intention—hardly fitting with the subconscious or automatic methods of Abstract Expressionism. Lewis was not involved in any of the iconic Abstract Expressionist moments. He was not a signatory of the letter of protest against the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition American Painting Today – 1950. He was not present in the subsequent photograph of the “Irascibles” that appeared in Life Magazine. Nor was Lewis one of the artists who exhibited in the 9th Street Exhibition of 1951, which established the careers of many members of the movement. But if Lewis was not “one of the only” Black Abstract Expressionists, nor even an Abstract Expressionist at all, why is he so frequently lumped into that narrative? This is a question worth asking, and perhaps this latest acquisition by the Whitney will help answer it, and perhaps even reframe the Lewis legacy, elevating it to its proper level.

The Art of Social Change

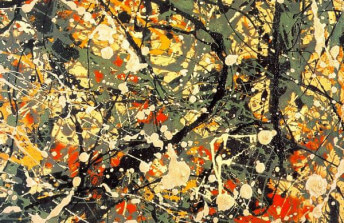

One reason the Whitney gave for acquiring “American Totem” is the “brilliant” way that it expresses what the call the political and aesthetic concerns Lewis had. Yet this explanation is a bit superficial. The painting is about 80 per cent black and 20 per cent white—a vertical composition of white forms dominates the lower center portion of the canvas, like a wedge, or a divide. The white forms are interpreted in the Whitney press release as representing the “totem” in the title; a totem is something symbolic of a certain quality. At the apex of this supposed totem is a white triangle. Beneath the white triangle sits a white, rectangular form marked by the presence of two black circles. The combination of the triangle, the rectangle, and the two black circles is said to be reminiscent of a Ku Klux Klan hood. We are therefore told that Lewis intended the white forms in this painting to suggest that the quality of “Americanism” has something to do with the type of vile racism espoused by the Klan.

This reading of “American Totem” is rather trite. The work belongs to a collection of Lewis canvases collectively known as his “Civil Rights” paintings—painted during a time when he was interested in showing solidarity between Black artists and the Civil Rights Movement. But Lewis had been painting abstractly for more than a decade when he painted it. He had long since abandoned straightforward figuration as a way of conveying social messages. Aside from the visual reference to a white hood, is there anything else going on in this image that we should pay attention to? Might we consider the worn surfaces, which suggest the ravages of time? Might we focus more on the notion of division suggested by the composition, rather than attributing all of the focus to one fringe, radical group? Rather than seeing the black circles as holes for white eyes, could we see them as two black figures searching in a landscape of pure possibility? Why must the white forms be the subject matter? Most of the canvas is black. Why is the blackness not the subject matter? We can do better than just looking for pareidolia in this painting. Lewis deserves more respect than such a shallow and basic interpretation.

A One-Artist Movement

Perhaps one reason such a simplistic interpretation has been given to “American Totem” is because it helps explain something unexplainable to a public with a limited attention span. Lewis defies allegiance to any one specific art movement, so it is convenient to lump his works into a collection of readymade political and social pronouncements. It is more difficult, but more accurate, to admit that we have only just begun to understand “American Totem” and the rest of the work this artist did. Like Vincent Van Gogh, Marcel Duchamp, Georgia O'Keeffe, Louise Bourgeois, and Agnes Martin, Norman Lewis was a movement unto himself. His work evolved according to his own inner development as an artist and as a human being. It transcended everything his peers were doing at the time, and adhered only to his own sense of what was beautiful and true.

In fact, one of the only verifiable connections Lewis had to the Abstract Expressionist movement was that he was the one Black artist invited to participate in the Studio 35 Artist Sessions, a series of discussions hosted in 1950 by Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline at which the serious aesthetic topics of concern to New York artists at the time were aired, around a table in a smoke-and-artist-filled room. Lewis contributed many enlightening comments to the discussions, one of which offers essential insight into our understanding of his practice. When asked when he knows a painting is “finished,” Lewis responded, “I have stopped, I think, when I have arrived at a quality of mystery.” Consider, therefore, that “American Totem,” and every other Lewis painting, was to some extent a mystery even to Lewis himself. Whatever meaning or interpretation we might assign it, we can never be complete in our assessment. Lewis went beyond the limitations of style and movement, and beyond his own awareness of his subject matter. Art movements, by defining their own boundaries, become a version of death. The mystery within the paintings of Norman Lewis is what endows them with their sense of life.

Featured image: Norman W. Lewis - American Totem, 1960. Oil on canvas. 74″ x 45″. Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York © Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio