Meet an Italian Spatialist Who is Not Lucio Fontana

Jun 26, 2019

Next month in London, a survey of more than 40 works will trace the entire career of Italian artist Paolo Scheggi (1940 – 1971). Paolo Scheggi: In Depth at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London will be the first extensive Scheggi exhibition in the UK. Throughout his short life—he died at the age of 30—Scheggi was consumed by thoughts of what exists beyond the surface. This pre-occupation manifested in both material and immaterial ways. In the immaterial realm, Scheggi consumed poetry and metaphysical philosophy, filling his studio, and sometimes his art, with poetic sentiments from the masters he admired, such as T. S. Eliot. He also founded the magazine “Il Malinteso” (The Misunderstanding), which scrutinized the visual languages of plastic arts. In the physical realm, he created a multi-dimensional body of art that strived to give concrete form to his search for what he called “justification for our existence.” Inevitably, his artworks were called abstract because they avoid narrative storytelling. But that word is incomplete in this case. What does it mean to say that an attempt to express the unseen or immaterial is an abstraction? Scheggi believed the truth of human existence was not to be found on the surface, but in the depths of our experiences. He mined those depths in every way that he could, through painting, sculpture, design, architecture, fashion and theater. His ideas were perhaps best expressed in his relief works, which adopted the visual strategies of Spatialism to demonstrate the essential truth that there exist a multitude of dimensions hidden beyond what we initially perceive with our eyes. Like his predecessor and inspirational forebearer Lucio Fontana, Scheggi knew that only if we dare to slash through superficialities can we begin to understand what lies beneath.

A Long Short Look

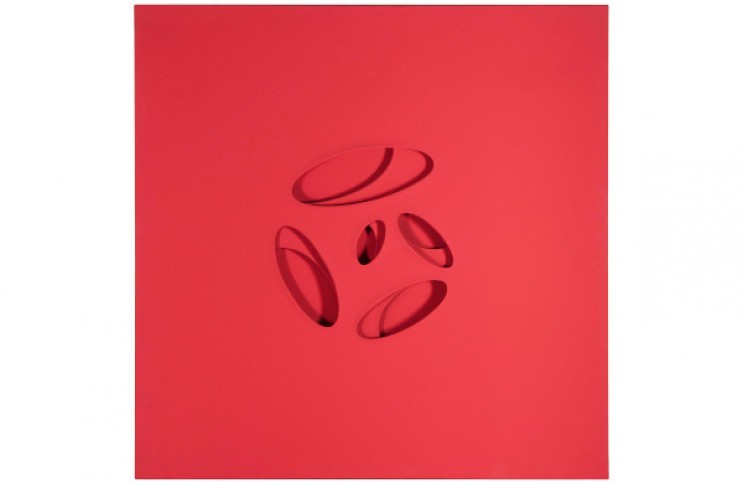

One of several witticisms embedded within the title Paolo Scheggi: In Depth is that Scheggi was only a productive artist for around 12 years. How in depth can any survey of such a short career be? Yet Scheggi was surprisingly productive, both intellectually and in the studio. The survey begins with a sort of visual blank slate: a series of monochromes Scheggi made of sheet metal when still a teenager. A monochromatic palette was something Scheggi maintained throughout his career, letting the purity of a single hue draw our focus to the spatial and dimensional aspects of his work. Next, after his monochromes, we see examples of a series Scheggi called “Zone Riflesse” (Reflected Zones). Directly referencing the slashed canvases made by Lucio Fontana, these works were created by stretching three canvases atop each other then cutting out elliptical shapes in each canvas so the empty holes in the canvases stack atop each other. The viewer can look beyond the surface of one monochrome surface into another, and then another. Light and shadow add visual depths while actual depths are created in the spaces between the layers.

Paolo Scheggi - Curved Intersurface in Orange, 1969. Orange acrylic on three superimposed canvases. 120 × 120 × 6.5 cm. Franca and Cosima Scheggi Collection, Milan.

Next comes examples of a body of work called “Intersurfaces.” These pieces also consist of layered canvases, but instead of identical shapes being cut out of the surfaces, different shapes are removed. The resulting effect is that unexpected geometric and biomorphic patterns emerge in the voids, suggesting unseen structures and continuations in the hidden spaces beyond what the eye can see. The “Intersurfaces” make emptiness the subject matter of the work, and suggest the possibility of visual subtext, literally inviting viewers to participate by “reading between the lines.” Participation is clearly a key point to the whole career of Scheggi—he obviously believed viewers should actively involve themselves in art in stead of just passively looking. Such ideas tie Scheggi in with movements such as Arte Programmata, an Italian kinetic art movement dedicated to creating new types of artworks, such as Italian philosopher Umberto Eco described as “no longer something immobile, waiting to be seen, but something in the process of becoming while we watched it.”

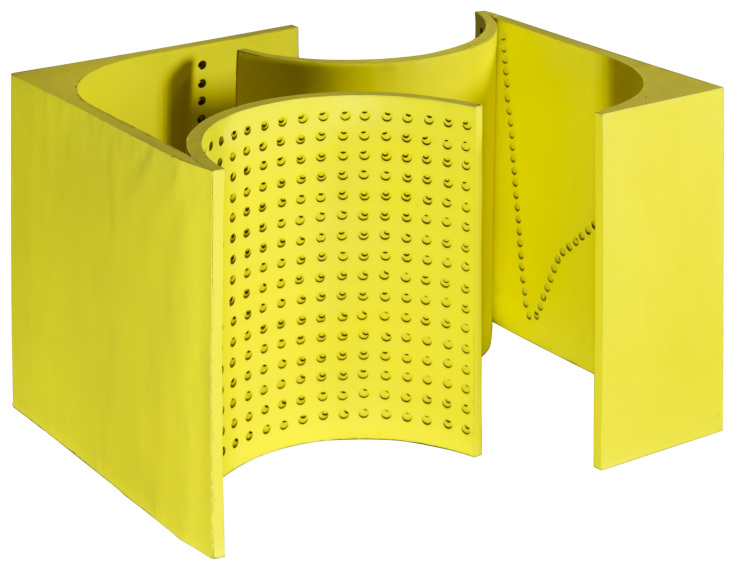

Paolo Scheggi - Maquette for the ‘Plastic Interchamber’, 1966. Sheets of curved, punched wood painted yellow. 52.5 × 86 × 66 cm. Franca and Cosima Scheggi Collection, Milan.

How Deep is Deep?

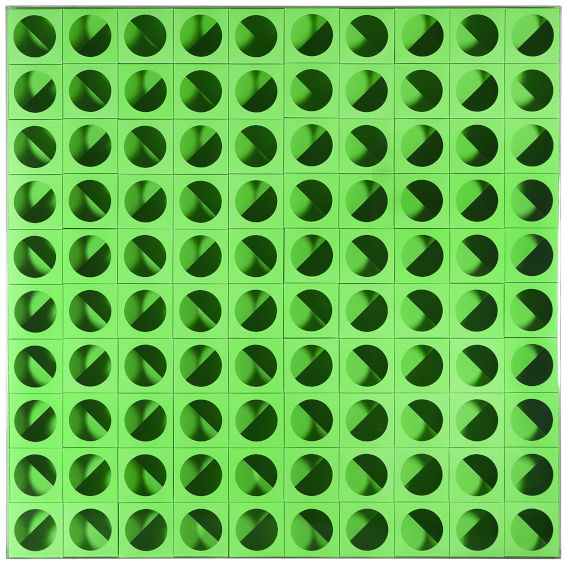

Another witticism embedded within the title of this survey is how much meaning is implied by the words in depth. What is depth? How do we find it? In a practical sense, we always inhabit the depths of physical space, we are never really on the surface of anything. Yet we always see into space, and feel that the only way to protrude into its depths is to move. Scheggi knew that movement is key to depth, and continued honing his visual concepts in order to further reward viewers who are willing to participate in the work through movement. He created a series of layered works where the top surface features circular cut outs arranged in a grid. These works mobilize shifting lighting conditions and the movement of the viewer to create an evolving network of seemingly symbolic geometric images within the fluctuating tableau. We cannot physically move into these depths, but we can peer into them, and imagine the further depths of meaning they imply.

Paolo Scheggi - Inter-ena-cube, 1968. Modules of punched green cardboard and Plexiglas. 102 x 102 x 11 cm. Franca and Cosima Scheggi Collection, Milan.

As this exhibition makes clear, however, had Scheggi survived longer he would have liked to create more works that viewers actually could have entered into. That is evident in his theatrical pieces, which are well documented by this show, and his fashion creations. But it is most especially evident in a model for something Scheggi called the “Plastic Interchamber” (1966), an environmental installation similar to a work Bridget Riley made three years earlier called “Continuum,” which allows viewers to enter the inter-spatial interiors of the work to become part of its visual and physical depths. Clearly, like so many artists of his generation, Scheggi was aware of the inexpressible depths of the human experience, and eager to find simple, exciting ways to examine them. Though he was not as prolific as Fontana, Riley, and the other artists who inspired him, his works do expand the depths of our perception in fresh, humble, and infinitely enjoyable ways. Paolo Scheggi: In Depth will be on view from 3 July — 15 September 2019.

Featured image: Paolo Scheggi - Curved Intersurface, 1965. Red acrylic on three superimposed canvases. 100 x 100 x 6 cm. Franca and Cosima Scheggi Collection, Milan.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio