How Piero Dorazio Brought Abstraction to Italy

Jan 15, 2020

Once again today we find ourselves in a time when the art field seems dominated by politically relevant art. As such, an age old question is again being debated: is abstract art inherently political, or is it inherently apolitical? This question was not alien to Italian artist Piero Dorazio, who came of age in the aftermath of World War II. Dorazio was one of many artists from his generation who believed wholeheartedly that abstract art was the most political kind of art a person could make. Born in 1927, Dorazio likely grew up knowing a little about the history of that other group of Italian abstractionists, the Italian Futurists. The society in which he was raised was still reeling from the beliefs they embodied, and the effects of the war-hungry, fascist fervor those artists espoused in their 1909 Futurist Manifesto. Like many of his contemporaries, Dorazio rejected such violent, Fascist political beliefs, which he had witnessed leading his nation to the brink of annihilation. Nonetheless, he saw something in Futurist art that he believed transcended their nihilistic politics. The Futurists embraced abstraction as a way to directly express certain human experiences, like movement and speed. Believing that they were on the right track, but were just misguided in their social ideals, Dorazio sought to liberate Italian abstract art from the legacy of the Futurists. In the 1950s, he befriended the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, then in his 70s and living in Rome. He visited Bala frequently and learned everything he could about the purely formalist aspects of his art. Dorazio became convinced that the real power of abstraction lay in the ability of color and light to communicate universally to all people. He embraced this abstract principle as an inherently political ideal and spent the rest of his life trying to communicate it through his art.

Forma 1 Group

In 1947, Dorazio joined a small group of Italian artists who had formed a collective known as the Forma 1 Group. Their name was derived from the title of a magazine called Forma, of which they published only a single issue. That issue included a manifesto signed by Dorazio along with Carla Accardi, Ugo Attardi, Pietro Consagra, Mino Guerrini, Achille Perilli, Antonio Sanfilippo and Giulio Turcato. The manifesto was an attempt to reconcile the fact that these artists considered themselves Socialists, and yet unlike the official Socialists of their time they did not believe in the necessity to create Socialist Realist art. The principles of Socialist Realism demanded that only figurative paintings and sculptures that directly conveyed the realities of everyday working working people could have value and meaning for society. The Forma 1 Group manifesto laid out an alternative belief that abstract art could also be politically relevant and socially important so long as it, too, was based on something universally relatable.

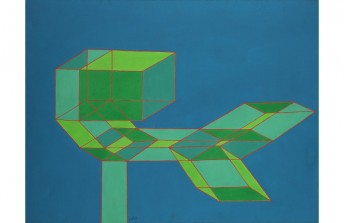

Piero Dorazio - Untitled V, 1967. © Piero Dorazio

Their vision of abstraction rejected sentimentalism and emotion, instead prioritizing formal elements like structure, harmony, beauty, color, mass and form. Rather than conjuring abstract compositions from the metaphysical void in the tradition of Kandinsky, or manifesting them from the pseudo-psychological realm like the Surrealists, the artists of Forma 1 Group sought to create a sort of concrete abstraction founded on the visual elements of the real world. They called themselves “formalists and Marxists,” two terms they claimed are not mutually exclusive. Dorazio insisted that this brand of Socialist Abstraction was not only important to everyday people, but was in fact even more relatable since it did not rely on regional or culturally specific references, but instead was based on the colors, shapes, forms and light that could in theory be instantly recognizable to anyone living on planet Earth.

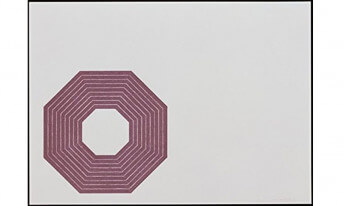

Piero Dorazio - Cercles de Nuit, 1992. Color lithograph. © Piero Dorazio

An Aesthetic Cultural Bridge

Using color and light as his two main tools, Dorazio created a body of work that employs the grid as its visually unifying force. Aside from that basic starting point, however, he experimented with many different compositional systems. His brush strokes vary between wild gesturality and precision. Some of his paintings have hard edges, some come together in frenetic crosshatch patterns, while in others Dorazio allows the paint to freely drip. Oil paintings such as “Piccolo Mattutino” (1958) are so gestural and energetic that they seem almost like the work of an Abstract Expressionist. However, the underlying structure of that painting reveals that the composition was meticulously laid out and has a strong underlying visual architecture. Densely layered, the colors and tones of the composition are harmoniously balanced. Whereas an Abstract Expressionist painting foregrounds its spontaneous emotional aspects, this painting succeeds according to its grounded sense of control.

In many respects, the range of different visual strategies Dorazio worked with made him an aesthetic bridge across various abstract trends that came and went around the world in the 20th Century. His paintings have been variously described by critics as Lyrical Abstraction, Tachism, Post Painterly Abstraction, Op Art and Minimalism. Each of those labels makes a bit of sense, but then again none of them do. Dorazio was not following styles; he was painting real things that he wanted us to recognize. He was painting forces like energy, movement and light. He was painting patterns and structures that he believed are essential to the natural and built worlds. This is the most important thing to remember today when once again we are debating whether abstraction and formalism is relevant to the social and political culture of our time, and whether abstraction has anything to say to people about their everyday lives. If we focus too much on trying to categorize the trends an artwork seems to be in line with, we miss out on the underlying universalities the work expresses. That is what made the work Piero Dorazio fundamentally political: its ability to connect with the human experience no matter whom, or from where, a particular human happens to be.

Featured image: Piero Dorazio - Rosso Perugino, 1979. Oil on canvas. 90 x 130 cm. © Piero Dorazio

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio