The Psychology Behind Shape and Form

Why does abstract art appeal? Often considered to be a visual language of shape, color and form, there is something very particular in the attraction to an abstract work of art. Several theories exist which aim to explain the psychology behind the spectator’s enjoyment, and the artist’s creation, of abstract art. The effects of trauma in artists can often be observed in a noticeable shift towards abstraction: famously, Willem de Kooning continued to paint after developing Alzheimer’s disease, after which his style became increasingly abstract. The example of de Kooning, and many others like him, demonstrates that art can provide insight into the changes of the human brain that alter expression and perception. In the following report, we will address some of the psychological theories attached to abstract art.

Neuroaesthetics: Introducing Scientific Objectivity to the Study of Art

During the 1990s, vision neuroscientist Semir Zeki of University College London founded the discipline known as neuroaesthetics which examines, from a neurological basis, the relative success of different artistic techniques. Several scientific studies looking into the reasoning behind an attraction to abstract work have concluded that studying this genre of art stimulates very active neural activity as the spectator struggles to identify familiar shapes, thus rendering the work ‘powerful’. Seeing the work as a puzzle, the brain is pleased when it manages to ‘solve’ this problematic (Pepperell, Ishai).

One particular study, led by Angelina Hawley-Dolan of Boston College, Massachusetts (Psychological Science, volume 22, page 435), questioned whether abstract art, created by professional artists, would be as pleasing to the eye as a group of random lines and colors made by children or animals. Hawley-Donan asked volunteers to look at one painting by a famous abstract artist, and one by an amateur, child, chimp or elephant, without prior knowledge of which was which. The volunteers generally preferred the work by the professional artists, even when the label told them that it was created by a chimp. The study concluded, therefore, that when looking at a work, we are capable – although we cannot say why – of sensing the artist’s vision. Hawley-Dolan’s study followed the findings that the blurry images of Impressionist art stimulate the brain’s amygdala, which plays a central role in feelings and emotions. However abstract art, which often seeks to remove any interpretable element, does not fall into this category.

Taking inspiration from this study, Kat Austen in New Scientist (July 14th, 2012), interrogates the appeal of abstract art, inspired by the effect of viewing a work by Jackson Pollock, Summertime: Number 9A which, she writes, was the first time a work of abstract art had stirred her emotions. Austen raises the hypothesis that works of abstract art which seemingly contain no recognisable object for the brain – namely Rothko, Pollock and Mondrian – may have an effect through well-balanced compositions as they appeal to, or ‘hijack’, the brain’s visual system.

In a study by Oshin Vartanian at the University of Canada, in which the researcher asked volunteers to compare a series of original paintings to one in which the composition had been altered, Vartanian discovered that we have a heightened response to pattern and composition. Almost all the volunteers preferred the original work, even when working with such diverse styles as a still-life by van Gogh and Bleu I by Miró. The findings suggested that the viewer is inherently aware of the spatial intention behind the paintings’ particular compositions.

To return to Austen, she also considers the findings of Alex Forsythe, a psychologist at the University of Liverpool, who has made a link between the forms used in abstract art and the brain’s ability to process complex scenes, making reference to the work of Manet and Pollock. Using a compression algorithm to measure the visual complexity of works of art and store complex images, Forsythe concluded that some artists may make use of this complexity to appeal to the brain’s need for detail. Forsythe also explored the brain’s attraction to fractal patterns and the appeal of abstract art. These repeating patterns, taken from nature, may appeal to the human visual system that evolved outdoors, and Forsythe reasons that abstract artists may use color to “soothe a negative experience we would normally have when encountering too high a fractal content”. Austen points out that neuroaesthetics are still at a nascent stage, and that it may be too early to make sweeping statements. However the multiple theories to have been addressed through this area of study do give us greater insight into the visual attraction of abstract art. Not least, some scientists have reasoned that the brain may be attracted to work by artists including Pollock, as we process visual movement – such as a handwritten letter – as if replaying the creation. This could be one understanding of the perceived dynamism of works by Pollock, whose energetic production is relived by the viewer.

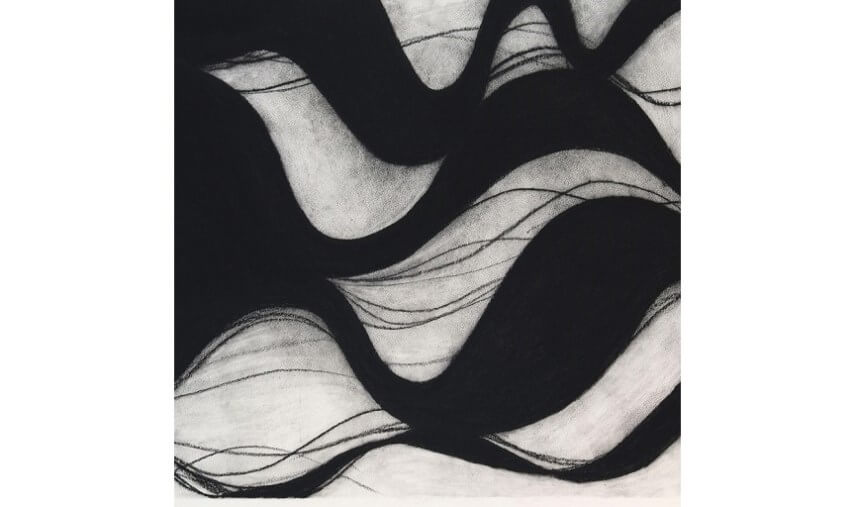

Margaret Neill - Manifest, 2015. Charcoal and water on paper. 63.5 x 101.6 cm.

Margaret Neill - Manifest, 2015. Charcoal and water on paper. 63.5 x 101.6 cm.

Wassily Kandinsky:On the Spiritual in Art

Let us now go back to around a century ago, to one of the leaders of German Expressionism, known for his role as a synaesthetic artist: Kandinsky played a central role in early 20th century theories about the psychology behind abstract art. His book ‘On the Spiritual in Art’, published in 1911, came to be known as the foundation text of abstract painting and explored in great detail the emotional properties of shape, line and color. Kandinsky’s synaesthesia manifested itself in his abnormal sensitivity to color and his ability not only to see, but also to hear it. Because of this, he reasoned that a painting should evade intellectual analysis, and instead be allowed to reach the parts of the brain connected with the processing of music. Kandinsky believed that color and form were the two basic means by which an artist could achieve spiritual harmony in composition and he thus separated the creation and perception of art into two categories: internal and external necessity. Making reference to Cézanne, Kandinsky suggested that the artist created the juxtaposition of linear and colorist forms to create harmony, a principle of contrast that Kandinsky wagered was the "most important principal in art at all times". We can apply one of Kandinsky’s principals, as discussed in this academic work, to Jackson Pollock’s artistic practice, whereby he placed canvasses on the floor and dripped paint on them from high. For Kandinsky, the artist must not adhere to the rules of art and must be free to express themselves by whatever means possible: an essential factor for internal necessity. According to Edward Lavine, painting, for Pollock, "becomes an experience [in] which the work has demands of its own which exist independently from the personality of the painter. These demands often seem to require the giving up of personal choice in favor of the inner necessity of the work." (Mythical overtones in the work of Jackson Pollock) To some extent, this theory contradicts that of Forsythe and others mentioned, as it implies the artist has limited choice in the creation of the work. Nonetheless, it does demonstrate the power of the process of creating abstract art.

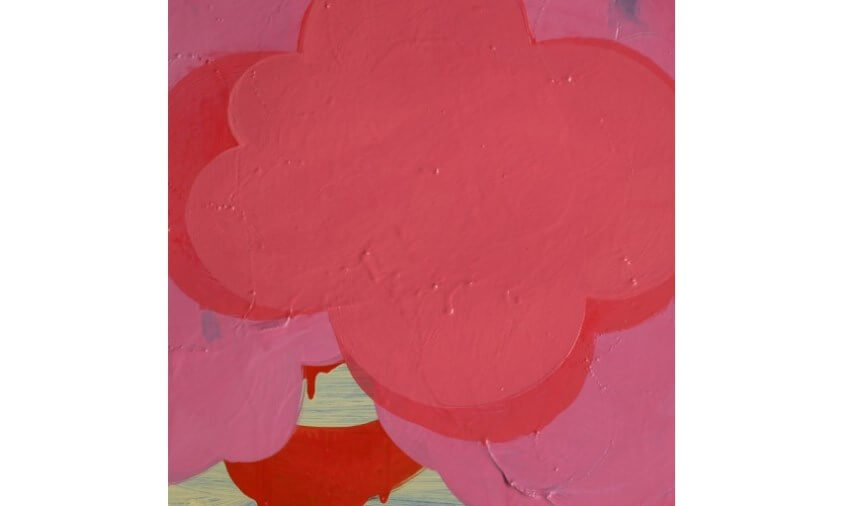

Anya Spielman - Bury, 2010. Oil on paper. 28 x 25.4 cm.

Peak-Shift

The basic idea behind the principle of peak-shift is that animals can respond to a greater degree to a more exaggerated stimulus than to a normal one. The concept, originally articulated by ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen, was applied by V.S.Ramachandran and William Hirstein in the 1999 paper The Science of Art, who applied the seagull experiment – whereby chicks will peck just as readily at a red speck on a mother’s beak as they will a stick with three red stripes at the end of it – to demonstrate that chicks respond to a ‘super stimulus’, here represented by the amount of red contour. For the two men, this stick with the red end would be akin to, say, a masterpiece by Picasso in relation to the level of response achieved by the spectator.

Ramachandran argued that abstract artists manipulate this theory to achieve the most positive results, by identifying the essence of what they want to depict, exaggerating it, and getting rid of everything else. According to Ramachandran, our response to abstract art is a peak-shift from a basic response to some original stimulus, even though the spectator might not remember what the original stimulus was.

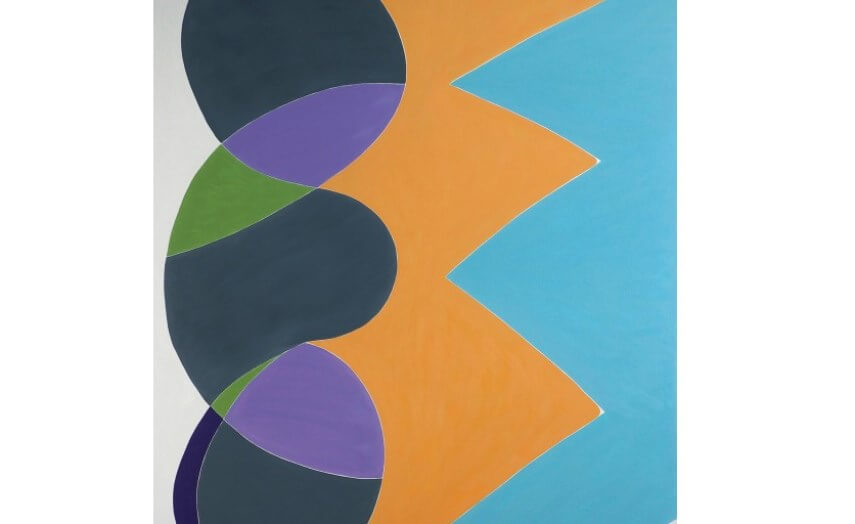

Jessica Snow - Worlds Rush In, 2014. Oil on canvas. 60 x 54 in.

Jessica Snow - Worlds Rush In, 2014. Oil on canvas. 60 x 54 in.

Brain Damage and Abstraction

To return to de Kooning, studies have shown that the brain does not have one single art center, but instead uses both hemispheres to create art, something which can have an effect on artistic ability or on the nature of artistic production following brain damage or neurodegenerative disease. According to Anjan Chatterjee for The Scientist, damage to the right side of the brain can result in spatial processing impairment, often leading to the adoption of an expressive style which does not require the same degree of realism. Similarly, brain damage to the left side of the brain can inspire artists to use more vivid colours in their work, and to change the content of their imagery. Californian artist Katherine Sherwood’s style was deemed to be more ‘raw’ and ‘intuitive’ by critics following a left-hemisphere hemorrhagic stroke. Not restricted to the production of art, brain damage can also alter an appreciation of art, says Chatterjee. More specifically, damage to the right frontal lobe can impair judgement of abstractness, realism and symbolism, and damage to the right parietal lobe can affect judgment of animacy and symbolism.

Gary Paller - 20 (2015) Blue, 2015. 59.1 x 45.7 in

Gary Paller - 20 (2015) Blue, 2015. 59.1 x 45.7 in

Prestige over Production

There is significant evidence to suggest that we respond more positively to art based on how we experience it. When presented with a work of abstract art, people rate it as being more attractive when they are told that it is from a museum than when they believe it has been computer-generated, even if the pictures are identical. This functions on various different psychological levels, stimulating the part of the brain that processes episodic memory – the idea of going to a museum – and the orbitofrontal cortex, which responds more positively to the element of status or authenticity of a work, than to its true sensory content, suggesting that knowledge, and not visual image, plays a key role in our attraction to abstract art. Similarly, it might be the case that we gain greater pleasure from remembering information about art and culture.

Greet Helsen - Sommerlaune, 2014. Acrylic on canvas. 70 x 100 cm.

Greet Helsen - Sommerlaune, 2014. Acrylic on canvas. 70 x 100 cm.

Abstract Art Appeals to Artists

Further studies have shown why abstract art may appeal more acutely to specific groups of people, namely artists. Recording the electrical rhythms occurring in the brains of non-artists and artists, a study showed that the subject’s artistic background greatly influenced the processing of abstract art, revealing that artists demonstrated focused attention and active engagement with the information. One theory suggests that this may be because the brain is using memory in order to recall other works as a way of making sense of the visual stimulus. It is this sense of recall and a multilayered process of searching for recognition which seems to provide abstract art with much of its enduring appeal. From Kandinsky’s explorative 1911 work, to the concept of peak-shift, and to the contemporary study of neuroaesthetics, the psychology of abstract art is a vast and ever-changing field of study which affirms the enduring interest in seeking to decode, explain and enjoy abstract art.

Featured Image: John Monteith - Tableau #3, 2014, 47.2 x 35.4 in