Why Richard Anuszkiewicz Was a Major Force of Op Art

Art movements never die. They just nap until some new genius wakes them up again so they can pick up where their past masters left off. Or sometimes, as in the rare case of Op Art, thanks to one of its most enduring pioneers, Richard Anuszkiewicz, an art movement is allowed the privilege of moving forward uninterrupted, generation after generation. Op Art emerged in the 1960s, and it has never really gone away. Along with Bridget Riley, Anuszkiewicz was, until 2020, one of its living legends. A former pupil of Josef Albers at Yale, Anuszkiewicz was on the vanguard of a trend away from personal emotion and drama in art, and toward the investigation of objective formal relationships, and the effect those relationships have on our eyes and minds. What made Anuszkiewicz stand out among his contemporaries, and what kept him relevant long after most of them have quit, is not only the brilliance of his work, but the seriousness and humility with which it was made.

Discovering Color

One of the most endearing stories about Richard Anuszkiewicz is that of his first solo show in New York City. The story begins back in Ohio, where Anuszkiewicz earned his Bachelor of Arts degree at the Cleveland Institute of Art. In his fifth and final year at that school, he earned a fellowship to go study art in Europe. But after expressing to his advisor that he had no interest in Europe, he was encouraged instead to pursue graduate studies at either Cranbrook, a progressive art school outside of Detroit, or Yale. After learning that Josef Albers, the famous colorist with roots in the Bauhaus, was at Yale, Anuszkiewicz chose to go there. Regarding his choice, he later explained that he felt color was the biggest thing missing from his work.

Though Albers was, and still is, considered a genius, he was not a universally beloved teacher. Many found his lessons arbitrary, boring—even useless. But Albers did not care what his students thought. He believed in the inherent worth of understanding color relationships, so that is all he taught. If a student did not understand or show interest, it was all the same to Albers. But Anuszkiewicz happened to be that rare student who fully understood the importance of what Albers taught. He excelled in his classes. He even became convinced by Albers to abandon figuration, accepting that the only way to truly explore the power of color is to make it the central subject of the work. But there remained one central problem for Anuszkiewicz, and that is that under the weight of the powerful personality Albers wielded, it was nearly impossible for his students to develop an individual style.

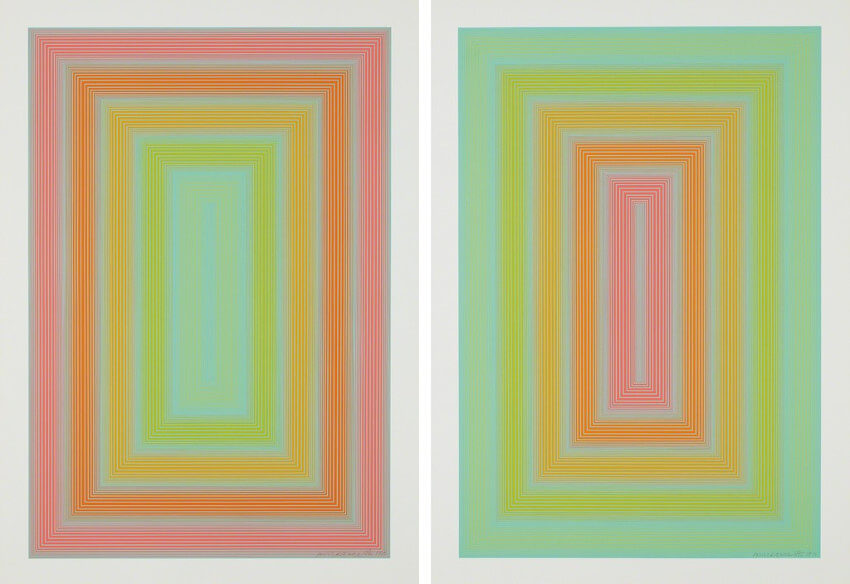

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Rosafied; and Veridified, 1971, Two screenprints in colors, on wove paper, with full margins, 36 × 26 in, 91.4 × 66 cm, © Richard Anuszkiewicz

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Rosafied; and Veridified, 1971, Two screenprints in colors, on wove paper, with full margins, 36 × 26 in, 91.4 × 66 cm, © Richard Anuszkiewicz

Last Minute Success

After completing his Masters at Yale, Anuszkiewicz took the unusual step of returning to Ohio to earn an additional degree in education in case he ever wanted to teach. It was there, finally free from the influence of Albers, that he arrived at a style of his own. It was an exploration of how the relationships between colors and shapes could fool the eye and make the mind see things that are not there. He found this experience transcendent and contemplative, and its paradox poetic. After completing his education degree, Anuszkiewicz felt that for the first time he had a strong, idiosyncratic idea, and plenty of good examples of his work. So he moved to New York and began showing his work to gallerists. But despite many who thought the work intriguing, no gallerists wanted to take a chance on showing it. It was 1957. Abstract Expressionism was still the rage. Dealers just were not sure whether the flat, colorful, hard-edge works Anuszkiewicz was making would sell.

It took two years before Anuszkiewicz was finally signed by Karl Lunde, at The Contemporaries Gallery. Lunde offered him a solo show in March of 1960. That show ended up being fabulously well attended. Many critics and collectors buzzed happily about the work. But as all of the other dealers had predicted, nobody was buying. In fact, almost the entire show went by without a single sale until, on nearly its last day, one buyer finally walked in: Alfred F. Barr, Jr., who happened to be the Director of the Museum of Modern Art. Barr purchased a painting called Fluorescent Complement, and exhibited it later that year at MoMA with other recent acquisitions. Like clockwork other collectors began acquiring works by Anuszkiewicz, including some of the wealthiest collectors in the city, such as Nelson Rockefeller.

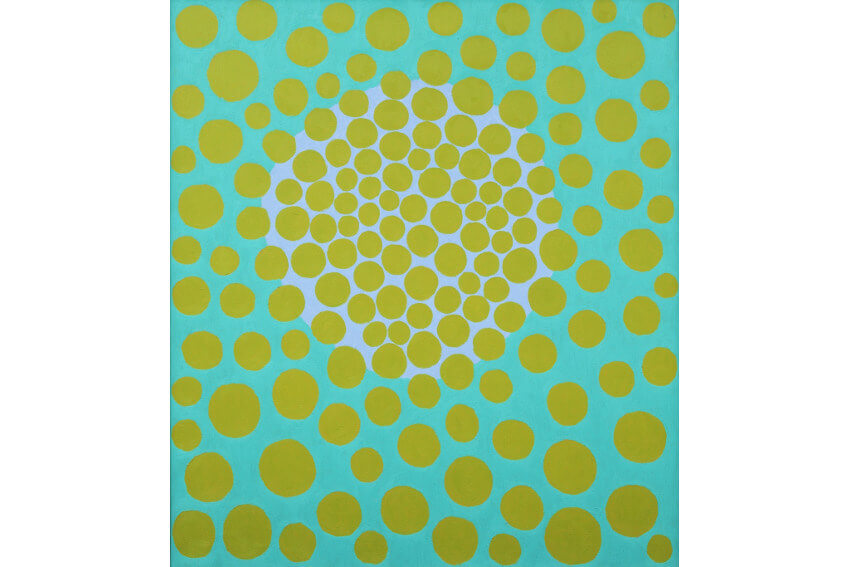

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Fluorescent Complement, 1960, Oil on canvas, 36 x 32 1/4 in (91.5 x 82 cm), MoMA Colection, © Richard Anuszkiewicz

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Fluorescent Complement, 1960, Oil on canvas, 36 x 32 1/4 in (91.5 x 82 cm), MoMA Colection, © Richard Anuszkiewicz

The MoMA Effect

The presence of Fluorescent Complement at MoMA signaled to the public that it was time for Abstract Expressionism to take a nap. The following year, the Whitney hosted Geometric Abstraction in America, which included an Anuszkiewicz painting, and then MoMA announced a major upcoming exhibition dedicated to “a primarily visual emphasis.” When that major exhibition, which was called The Responsive Eye, finally occurred, it included the work of scores of artists and solidified the meaning of the term Op Art. And along with Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley, Anuszkiewicz emerged as one of the most important artists in the show.

It is said what separated Vasarely was his mastery of light and darkness, what separates Riley is her master of line, and what separated Anuszkiewicz was his mastery of color relationships. But there is something else about all three sets them apart—their seriousness. They all three possess intrinsic curiosity and dedication. And Anuszkiewicz was also special for his humility. While writers gush about his achievements, he makes comments like, “Something does happen when you put two colors together. It has an effect.” He played down the brilliance and power of his work, simply referring back to the notion that colors and shapes change in different situations, and contemplating such changes can remind humans that we are never quite sure whether what we are looking at is real.

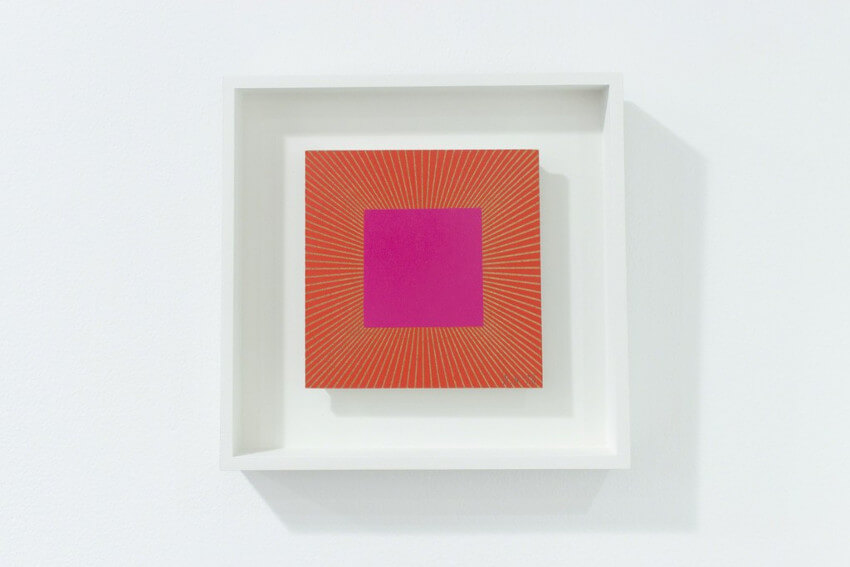

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Unnumbered (Annual Edition), 1978, Paint and screenprint on masonite, 4 × 4 in, 10.2 × 10.2 cm, Loretta Howard Gallery, New York City, New York © Richard Anuszkiewicz

Richard Anuszkiewicz - Unnumbered (Annual Edition), 1978, Paint and screenprint on masonite, 4 × 4 in, 10.2 × 10.2 cm, Loretta Howard Gallery, New York City, New York © Richard Anuszkiewicz

Featured image: Richard Anuszkiewicz - Untitled (Annual Edition), 1980, Screenprint on masonite, 5 3/4 × 5 3/4 in, 14.6 × 14.6 cm. © Richard Anuszkiewicz

All images used for illustrative purposes only