The Late Abstract Expressionism in the Works of Sam Francis

Some people say that for true artists, making art is not a choice; it is a compulsion. They make artworks whether they get paid or not, even if they get ignored. In other words, artists make art because they cannot not make art. As serious as that sounds, Sam Francis considered the relationship between artists and art making to be even more intense. He saw art making not as something an artist does, but something that simply is because the artist is. He said, “the artist is his work and no longer human.” For Francis, separating art from an artist was as impossible as separating rain from a cloud. The rain is the cloud. The art is the artist. There is no separation. They are one.

Darkness Is Only a Color

When looking back at the history of Abstract Expressionism, it becomes apparent rather quickly that the artists associated with the early days of the movement were deeply influenced by the anxieties of their time. They were of a generation defined by suffering and sacrifice, haunted by the horrors of war and fear of the atom bomb. Through their artworks they earnestly attempted to connect with their subconscious and to express their inner states of being. The darkness of their time often seems evident in their art, either in the color palette or in the angst of the gestures, forms, textures or compositions. But those same works are also revelatory, leading viewers to experience transcendent, contemplative states of consciousness. So is it truly darkness they express?

Sam Francis is associated with the second generation of abstract expressionism. He rose to prominence after being included in the 12 American Artists exhibition at MoMA in 1956, the same year Jackson Pollock, the leading figure in the early movement, died. Francis took up painting in the hospital while recovering from a spinal injury he suffered while serving as a fighter pilot in World War II. After the war he returned to school in his native California, earning a Masters Degree from UC Berkeley in 1950. While there he met some first generation Abstract Expressionist painters, including Mark Rothko who was teaching at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco at the time. Francis found inspiration in the focus these creatives had on being and becoming, and in their commitment to the search for the authentic self.

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1959, gouache on paper, 11.5 x 36 cm. © The Sam Francis Foundation

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1959, gouache on paper, 11.5 x 36 cm. © The Sam Francis Foundation

The Marriage of Darkness and Light

For Sam Francis, darkness and light were not opposing forces. They were complementary forces, or perhaps even fluctuating manifestations of the same quality. He once said, “An increase in light gives an increase in darkness.” Was he saying light and darkness are one? Or was he talking about the way light casts a shadow, meaning the brighter a light becomes the darker shadow it casts? Or was he referring to enlightenment, and the metaphysical impact of realizing that the more we learn, the more we realize how little we know?

He could have meant none of those things. He also once said, “Color is born of the interpenetration of light and dark.” So it is possible he was simply speaking about contrasts, and how the white space on a canvas expresses the darkness of paint. In any case, his comments at least offer a nuanced perspective from which to interpret the apparent darkness of the abstract expressionist movement in general. And they give us a starting point for understanding the way he confronted darkness, light and color in his own paintings.

Sam Francis - SF 70 42, 1970. © The Sam Francis Foundation

Sam Francis - SF 70 42, 1970. © The Sam Francis Foundation

12 American Painters

Francis showed seven paintings in his breakout group exhibition at MoMA. They were massive in scale. The smallest was more than six feet tall and the largest was more than twelve feet by ten feet. The paintings were all named for colors: Blue Black, Yellow, Big Red, Black in Red, Red in Red, Gray, and Deep Orange on Black. Each of these paintings shared a common aesthetic, which established Francis as a painter with a defined visual style. They were composed of layered biomorphic forms enhanced by unrestrained drips.

These canvases envelope viewers in the compositions. The voice of the works redefines the word composition, to focus less on the arrangement of aesthetic elements and more on what it means to feel composed. They emit a sense of control, of confidence, and of harmony. They give off a sense that everything necessary to understand about the painting is contained with the space of the canvas. And yet their sensuous, personal nature invites us in to a deeper exploration of what else remains hidden within.

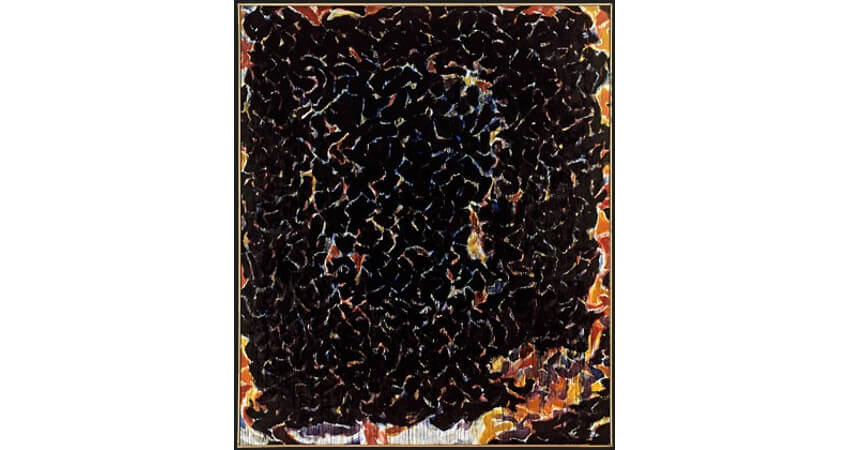

Sam Francis - Deep Orange on Black, 1955, oil on canvas. © The Sam Francis Foundation

Sam Francis - Deep Orange on Black, 1955, oil on canvas. © The Sam Francis Foundation

Containment

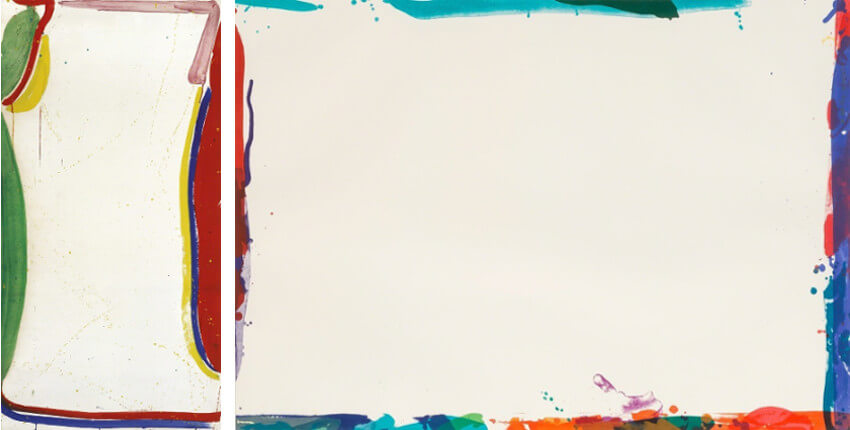

No sooner had Sam Francis become known for his unique aesthetic than he went beyond it. He expanded his color palette to include a vivid range of bright, pure colors. And he explored a multitude of approaches to composition, including biomorphic representation in a series of works called Blue Balls, which feature prominent blue orbs inspired by his battle with renal disease. In the mid-1960s, he arrived at another distinct aesthetic idiom characterized by colorful brushstrokes around the edges of his paintings surrounding nearly empty white space within.

These works speak directly and elegantly to the notions Francis expressed about lightness and darkness. The increased white space, or lightness, intensifies the expression of darkness that is conveyed through color. The color is minimized and yet defines the image. These pictures defy the all-over nature of so many abstract expressionist works. They speak to nothingness and to the power of nuance, and bring attention to what is not being expressed.

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1965, gouache on paper (Left) and Sam Francis - Untitled (SF-106A), 1969, lithograph (Right). © The Sam Francis Foundation

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1965, gouache on paper (Left) and Sam Francis - Untitled (SF-106A), 1969, lithograph (Right). © The Sam Francis Foundation

Without Restraint

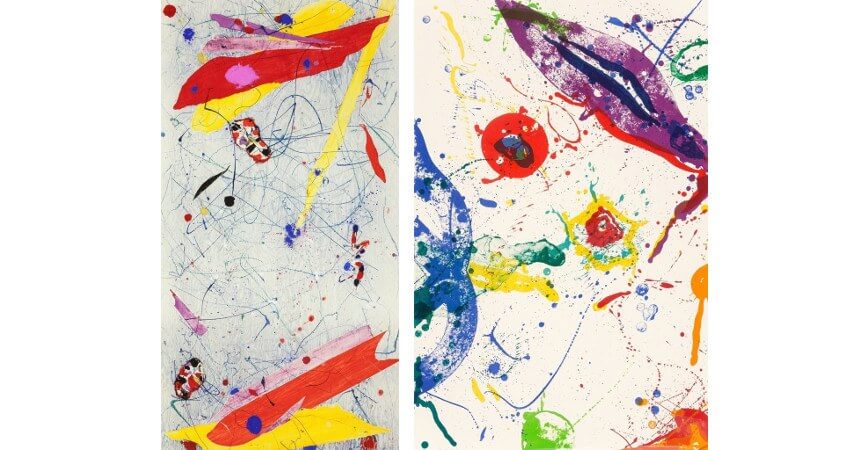

Throughout most of his career, Francis avoided the New York art scene, preferring to live and work in Paris, Tokyo and California. He was unrestrained by trends. He used the techniques associated with action painting, such as dripping, pouring and splattering, and also used staining and worked with traditional brushes. He made prints, lithographs and monotypes, working with a range of different mediums and surfaces. And he tirelessly evolved his compositional style. In the 1970s and 80s he often included geometric forms in his paintings, and sometimes even painted hardedge geometric works.

He is most often remembered for the brightly colored splatter paintings he created in the 1980s. Their adherence to techniques long abandoned by many other painters of his generation set them confidently apart. Their primitive qualities spoke in conversation with the Neo-Expressionist works of painters like Basquiat. Their color palette echoed that of Pop Art and the Chicago Imagists. And their imagery evoked abstract art history, harkening to painters like Miro, Calder and Gorky.

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1983, monotype (Left) and Sam Francis - Untitled (SF-330), 1988, lithograph on wove paper (Right). © The Sam Francis Foundation

Sam Francis - Untitled, 1983, monotype (Left) and Sam Francis - Untitled (SF-330), 1988, lithograph on wove paper (Right). © The Sam Francis Foundation

Beyond the Second Generation

Sam Francis never ceased his personal artistic evolution. Even after he lost the use of his right hand shortly before his death, he learned to paint left-handed and engaged in the creation of a large new body of work that he continued until he died. Despite changing his aesthetic style, he never abandoned the essential tenets of abstract expressionism. In his dedication to it, though, he also fundamentally transformed what abstract expressionism could be. Not to say that he altered it. He maintained its integral elements. He never ceased to paint intuitively, to connect with his own inner state of being, and to interact with the canvas as an arena in which an event occurs. But he also added to the definition. What he added is summed up nicely in his own description of what painting is: “Painting is about the beauty of space and the power of containment.”

Everything is in the four words, beauty, space, power and containment. Sam Francis unashamedly pursued beauty. He embraced both the limitations and the possibilities of a defined space. He acknowledged and took personal responsibility for the primal reality of the human quest for power. And, finally, he expressed the confidence and security inherent in the sense that something has been contained. Compare that to what Jackson Pollock once said about painting: “The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.” In addition to everything else their work was about, Pollock and the first generation of abstract expressionists were unrestrained in their experimentation. They were holding a wild tiger by the tail, excited to discover what it might do next, completely open to the possibilities, and most of all committed to keeping it as wild as possible for as long as possible. Sam Francis helped tame the tiger. In doing so he also gave the next generations of artists permission to define what abstract expressionism means to them.

Featured image:Sam Francis - Untitled, 1962, Acrylic and gouache on paper. © The Sam Francis Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio