5 Abstract Artworks From 'Soul of a Nation' Exhibition of African American Artists

The monumental exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power opened this month at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. This is the third venue for this extraordinary show, which opened at the Tate Modern in 2017 then traveled to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. The show features more than 150 works created by more than 60 artists. It covers a tremendous range of mediums—from painting, drawing and sculpture to textiles and garments—and spans numerous aesthetic positions—from straightforward figuration to Pop Art to pure abstraction. Back when the exhibition first debuted at the Tate, I had the privilege of sitting down with Gerald Williams, co-founder of AFRICOBRA, an influential black artist collective whose work is a major element of the exhibition. Williams had some fascinating things to say about the choice the curators made to include so many abstract works in the show. He was curious what viewers would have to say about how these works add to the conversation. So many Modernist abstract aesthetic positions are firmly rooted in historic transnational black aesthetics. And yet so frequently during the heydays of Modernism, black abstract artists were ignored by white run galleries because of blatant or subtle biases, or shut out of black run galleries because their work did not figuratively address black life. It is an immense pleasure to see so many abstract artists featured in Soul of a Nation. As the show settles in to its new temporary home in Brooklyn, we highlight five abstract works to look for if you happen to visit the show, which is on view through 3 February 2019.

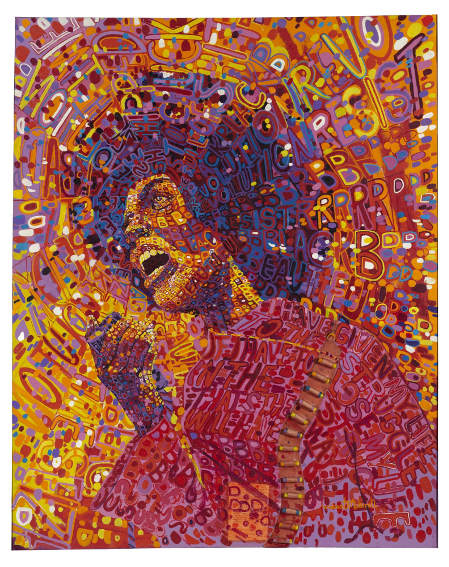

Wadsworth A. Jarrell, Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1971

One of the five founders of AFRICOBRA, Wadsworth Jarrell was integral to forming the philosophy of the group. That philosophy was outlined in the 1969 manifesto Ten In Search of a Nation. According to the manifesto, AFRICOBRA endeavored to make work that achieved: “1. definition—images that deal with the past; 2. identification—images that relate to the present; and 3. direction—images that look into the future” The key visual elements of their style were the use of text, luminescent “cool-aid” colors, and a mixture of abstract patterns and positive portraits of black people. “Revolutionary (Angela Davis)” spectacularly conveys each of these aspects. Additionally, it evokes early Modernist movements such as Futurism and Rayonism with its dynamic sharp angles, and Post-Impressionist movements like Divisinism with its mobilization of complimentary shapes and color relationships.

Wadsworth A. Jarrell (American, born 1929). Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1971. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 64 x 51 in. (162.6 x 129.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of R. M. Atwater, Anna Wolfrom Dove, Alice Fiebiger, Joseph Fiebiger, Belle Campbell Harris, and Emma L. Hyde, by exchange, Designated Purchase Fund, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Carll H. de Silver Fund, 2012.80.18. © Wadsworth A. Jarrell. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

William T. Williams, Trane, 1969

The appearance of Soul of a Nation in Brooklyn is somewhat of a homecoming for William T. Williams. One of the most accomplished and respected contemporary American abstract painters, Williams has taught art at Brooklyn College since 1971—two years after he painted “Trane.” This vivid, geometric composition is named for the American jazz composer and musician John Coltrane. The dynamic nature of the work evokes the lively, intuitive, and totally free sound for which Coltrane was known. But this work also relates to a personal history Williams has spoken of. He comes from a family of quilters. The quilts his ancestors made were dominated by colorful, linear, geometric patterns. “Trane” is part homage to family, part nod to a musical legend, and part expression of the singular abstract vision Williams conveys in his work.

William T. Williams (American, born 1942). Trane, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 108 x 84 in. (274.3 x 213.4 cm).

The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. © William T. Williams. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

Frank BowIing, Texas Louise, 1971

Although Frank Bowling was born in Guyana and has British citizenship, his contribution to American abstract art is profound. Bowling first came to New York in the mid-1960s and quickly became one of the foremost practitioners of lyrical abstraction. Most of his works occupy visual ground somewhere between Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting. Occasionally, figurative imagery, like ghostly outlines of continents, haunts his images. “Texas Louise” is a monumental work, engulfing the viewer in its glowing, textured red hues. It was painted the same year Bowling published the article It Is Not Enough to Say Black Is Beautiful in ARTnews. That piece addresses the complex views Bowling, and many artists, have had about labels such as “black arts,” “black artists,” or for that matter “abstract art” and “abstract artists.” It is worthwhile reading that essay again now, especially if you intend to visit this exhibition and see this important work.

Frank BowIing (American, born 1936). Texas Louise, 1971. Acrylic on canvas, 111 x 261 3⁄4 in. (282 x 665 cm).

Courtesy of the Rennie Collection, Vancouver. © Frank Bowling. Image courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery.

Norman Lewis, Processional (aka Procession), 1965

“Processional (aka Procession)” is emblematic of the signature ability Norman Lewis had to blend the methods of abstraction with symbolic or philosophical concepts. Lewis started out as a figurative painter. His abstractions frequently emerged out of a realistic starting point. This painting features emotive, gestural, calligraphic brushstrokes. The title and imagery evokes a line of people walking, suggesting perhaps the idea of a funeral. Integral to any figurative reading of the work is the question that if these brushstrokes are meant to suggest people, are the people white, or black, or both? This image could represent the death of the notion that there is any difference; or a procession forward towards a more enlightened era.

Norman Lewis (1909-1979), Processional (aka Procession), 1965. Oil on canvas, 38 3/8 x 57 5/8 in. (97.5 x 146.4 cm).

Private Collection; © Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Jack Whitten, Homage to Malcolm, 1970

Born in rural Alabama in 1939, Jack Whitten used to say he grew up in “American Apartheid.” His abstract style was rooted in symbolism. It served as a vehicle with which the artist could confront his feelings about culture, politics, and personal struggle. Whitten died in January of 2018, but not before he could see his stark and powerful “Homage to Malcolm” hanging in the Tate Modern. Recalling its creation in the days right after Malcolm X was assassinated, Whitten said, “The painting for Malcolm, that’s symbolic abstraction. Malcolm X had a grasp of the universal aspect of the struggle that he was involved with. It’s that conversion into the universal that gave him more power. That painting had to be dark. It had to be moody. It had to be deep.”

Jack Whitten (1939 - 2018). Homage to Malcolm, 1970. Acrylic on canvas, 104 1⁄2 x 118 1⁄2 x 2 1/8 in. (265.4 x 301 x 5.4 cm).

Courtesy the artist's estate and Hauser & Wirth. © Jack Whitten (Photo: Christopher Burke)

Featured image: Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. Installation view at the Brooklyn Museum in New York

By Phillip Barcio