The MoMA Collection Honors its Artists' Revolutions in “The Long Run”

Jan 3, 2018

A gauntlet has been thrown down, daring us to change the way we think about the careers of artists. The challenge comes via an essay written by Ann Temkin for The Long Run, a recently opened exhibition offering a deep dive into the MoMA collection. Titled Artistic Innovation in the Long Run, the essay takes issue with the fact that MoMA, like most museums, tends only to show works that reveal the most revolutionary accomplishments of important artists. This strategy highlights vital moments in art history, and provides a shorthand guide to the trajectory of the avant-garde. It pleases spectators, and therefore increases museum attendance, but it also implies that somehow art has to be spectacular in order to be valued. It ignores the long, experimental processes that lead to breakthrough masterworks, and fails to examine the evolutions those breakthroughs inspire in the mature work artists make later on. Worst of all, as Temkin mentions in her essay, it produces an art world culture that overvalues youth. Says Temkin, “We recently calculated the artists’ ages at the making of each painting and sculpture on view in our fifth-floor galleries (those covering the years from 1885 to 1950). More than two-thirds of the works were created when the artists were in their twenties or thirties.” Inherent ageism, incomplete assessments, and a skewed vision of art history—not a good legacy for a Modern Art museum. But if anyone can change this culture, and inspire a more profound, deep, and nuanced appreciation of aesthetics, it is Temkin. She holds arguably the top position in the American art world: the Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture. That means she helps decide what objects the most influential museum in the country buys, and holds sway over how its entire collection is exhibited. It is no exaggeration to say Temkin has the ability to influence the relationship between art, culture and contemporary society. The Long Run and its accompanying essay are compelling opening salvos in that effort.

Innovation Infatuation

Aside from Luddism and anachronism, almost every contemporary human activity includes an innate craving for originality. It would be unusual, for example, to pick up the latest science journal only to find articles promoting long ago supplanted medicinal theories. But new ideas and spectacular innovations were not always in fashion in the arts. Often in the past, tradition trumped novelty, and sophisticated people respected artists in balance with how time-tested their efforts were. Some cultures are even still like that. But for most part, the art world of today is obsessed with freshness, and has been at least since the 1930s, when Ezra Pound coined the battle cry of Modernism: “Make it new!”

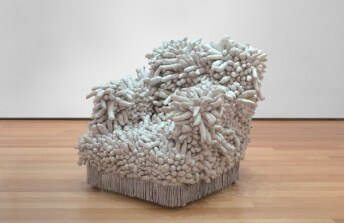

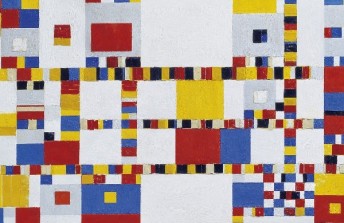

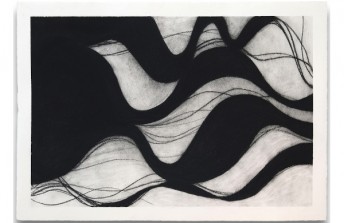

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Under the auspices of that directive, academics, curators and writers tend to narrate Modernist art history as though it has been just one innovation after another. Says Temkin, “we parade from ism to ism in a march of progress that leads from Post-Impressionism to Fauvism to Cubism, for example, or from Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism to Pop.” This, she says, demonstrates an “infatuation with innovation.” The Long Run offers an antidote. It does not discount isms and innovations. It simply poses the question, what followed them? The answer comes in the form of an experimental curatorial strategy—to rehang the part of the museum that used to show famous works from 1950s through the 1970s, focusing on the same artists but now exclusively showing works they made later in their careers.

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Curiosity and Refinement

What I love the most about this strategy, especially as Temkin expresses it in her essay, is how it differentiates between memorizing art history and developing an appreciation for everything that revolves around it. Knowing what kind of wine goes best with halibut is nice, but developing your palate to enjoy hidden nuances of flavor and aroma in every bottle of wine you open is another thing altogether. This exhibition calls us to develop our aesthetic tastes; to develop a sense of curiosity about art that will lead not only to knowledge, but to refinement. The end game Temkin is after is to expand our relationship with art. Instead of only going to see the most important paintings by the most famous representatives of the most well-publicized art movements, we may find ourselves seeking out unknown or new artists whose work is in the same tradition. We might start visiting smaller museums and galleries, or investing in artists and artworks that are less obvious, but equally sublime.

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

An evolution like this is overdue. The contemporary art world is losing its depth. As Temkin points out, “The parallel to the commercial world is unmistakable: new styles and names must come along like so many endlessly self-obsolescing phones and sneakers.” Just Google the phrase “artist having a moment” and see how much press is given to whatever art star or trend happens to have bubbled to the top of the market. The Long Run blows up the concept of moments. Rather than showing us one iconic Agnes Martin grid painting from the 1960s, it shows us works she made in the 1990s. Rather than famous works from the 1970s, we get to see what Gerhard Richter has been up to in the 2000s. Rather than a single artwork or a single era, we get to enjoy monographic exhibition rooms that take us far beyond what we thought was the end of the road. For many viewers this exhibition will be a revelation. For all of us, it is a chance to develop context and expand our tastes. Most importantly, it is a step towards overcoming the biases of our generation—to understand what it means not only for an artist to “have a moment,” but for one to cultivate an artistic life.

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

Featured image: Installation view of The Long Run. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 11, 2017–November 4, 2018. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck

By Phillip Barcio