The Abstract Side of Thomas Ruff Photographs

Nov 1, 2016

We may complain that digital manipulation has made all photographs suspect; but even in its non-manipulated condition every photograph is only a partial truth at best. The biggest illusion photography perpetrates is that it shows us what is real. A partial truth is by definition a partial lie. Thomas Ruff has never fallen for the false premise that photography is objective. Even though as a student he learned from some of the most respected documentary photographers of the 20th Century, Ruff has always accepted that falsehood is intrinsic to the camera. A lens requires omission, invites staging, and rewards artistic license. For Ruff, narrative content is the least important element of a photograph. More important are abstract qualities, such as composition, subtext, process, perspective, and the intent of the artist. Says Ruff, “Photography pretends to show reality. You can see everything that's in front of the camera, but there's always something beside it.”

The Becher Effect

Thomas Ruff acquired his first camera as a teenager. His earliest works were a combination of holiday snaps and imitations of the photographs he admired in magazines and newspapers. At age 19, he chose to devote himself full-time to becoming a photographic artist, and applied to the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. For his application, he assembled a collection of what he believed were his best works. They were good enough to get him accepted into the school. But he was later told by one of his professors that the pictures in his application were, “more or less stupid because those photographs were not [his] own photographs but clichés.”

The professor who made that comment was Bernd Becher, who, together with his wife Hilla, composed the most famous documentary photography duo in Germany. The Bechers first gained prominence in the 1950s for their iconic works documenting German industrial buildings. They had pioneered something they called Typology, which presented series of works of similar examples of architectural forms. Their intent was that their Typological series would serve an academic purpose by allowing viewers to analyze the structures and patterns in regional architecture, and by chronicling the idiosyncrasies of a passing era of industrial design. But they were also widely interpreted and appreciated as art.

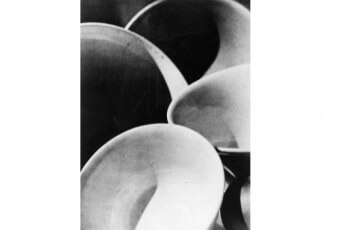

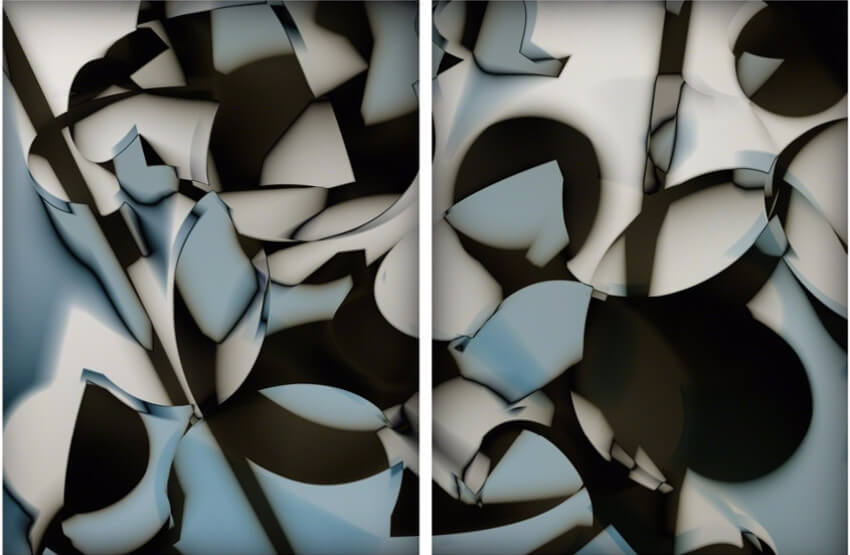

Thomas Ruff - r.phg 12, 2015. © Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff - r.phg 12, 2015. © Thomas Ruff

Taking Pictures vs. Making Pictures

The Typological work the Bechers did also inspired many abstract and conceptual notions. The effect of seeing multiple images of similar forms presented together, each framed the same, lit the same, and taken under the same conditions, inspired a range of different associations for viewers. The Bechers believed they were taking pictures, meaning capturing reality and presenting it to viewers. But Thomas Ruff saw that they were not capturing reality. They were artificially framing a point of view, editing what is real and presenting it to people from an abstracted, fictional perspective. To Ruff, they were not taking pictures; they were making pictures.

That distinction, between taking and making pictures, has been vital to the work Ruff has done since leaving the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1985. His early oeuvre includes stoic portraits of young German citizens, equally stoic portraits of German architecture, and night vision photographs of empty urban landscapes. Printed on a massive scale, they allow viewers an astonishing level of intimacy with their subject. And yet they obscure as much as they reveal. In the case of his portraits, the physical features are perfectly clear, but the facial expressions reveal nothing about the true identity of the sitters. Likewise, his works of buildings and his night vision pictures rely not on what they show for their power, but on what remains hidden from the lens.

Thomas Ruff - jpeg ib01. © Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff - jpeg ib01. © Thomas Ruff

In Appropriation

A common theme Ruff has explored since the late 1980s is that of appropriation. Instances sometimes arise when the vision of an artist requires collaboration. Sometimes that collaboration is invisible to viewers, such as when a manufacturer helps construct a sculpture. Other times, like in the case of content appropriation, when an artist borrows some element of the work of another artist, the collaboration is obvious. Whether it is in the form of a borrowed beat, a quoted verse or images for a collage, appropriation can be a sort of short hand that assists an artist in communicating something more directly than would have been possible without the appropriated content.

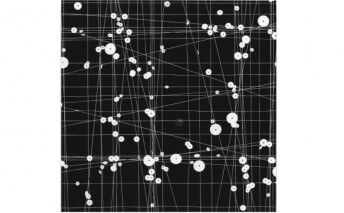

The first time Ruff used appropriation was in the late 1980s. He wanted to make abstract pieces of the night sky, but was unable to take adequately large works with his normal equipment. He sought a telescope he could use, but no owner of a large enough telescope would allow him access to take his pictures. His solution was to appropriate existing pictures of the night sky taken from the European Southern Observatory in Chile. He manipulated the photographs by enlarging selected areas to alter the viewer experience of scale. He then enlarged the prints to a massive size, offering a super-enhanced, illusionist perspective on the universe. In an abstract sense, these pieces flatten everything, democratizing the value of the figure and ground of the universe.

Thomas Ruff - r.phg.s.05.I (Left) and Thomas Ruff - r.phg.s.05.II, 2013. © Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff - r.phg.s.05.I (Left) and Thomas Ruff - r.phg.s.05.II, 2013. © Thomas Ruff

Content and Context

Ruff has also used appropriation in a variety of other ways in order to explore the abstract and conceptual potential of photography. In a series titled Nudes, he appropriated pornographic photographs from the Internet. He manipulated the color and the clarity of these images and enlarged them, distorting them to the point that the people became anonymous, blurry color fields. In some cases, he deconstructed these images until they lost their objective qualities entirely and could be appreciated solely according to their formal compositional elements.

In a project called Jpegs, Ruff elaborated even further on the rise of digital photography by appropriating found digital news images, such as images of war, and enlarging them until they were pixilated almost beyond recognition. When viewed up close, these massive pieces lose the emotional impact of their content. Rather than being consumed for their social, political or cultural relevance, they can be seen as collections of geometric shapes, lines and colors. Normally, a pixilated image would be considered low quality. But these massive pixilated pieces are of the highest quality as abstract photos. In both the Nudes series and the Jpegs series, Ruff vividly confronts us with the abstract idea underlying the work: the diminishing power of content in a digital world.

Thomas Ruff - Nudes, bu04, 2001. © Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff - Nudes, bu04, 2001. © Thomas Ruff

Digital Photographic Abstraction

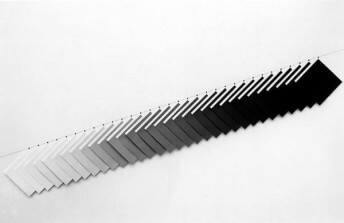

In the spirit of abstract photography pioneers, Thomas Ruff has also experimented with photograms. Essentially, a photogram is a photograph made without a camera. A simple example would be an object set on a piece of photosensitive paper in the sun. The paper would darken except for where the object was, creating a sort of reverse shadow image of the object on the surface. Artists such as Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy explored the abstract potential of the photogram nearly a century ago by. And the same technique is employed today in the abstract, handmade photograms of artists like Tenesh Webber.

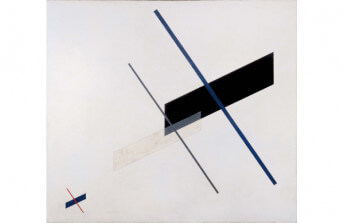

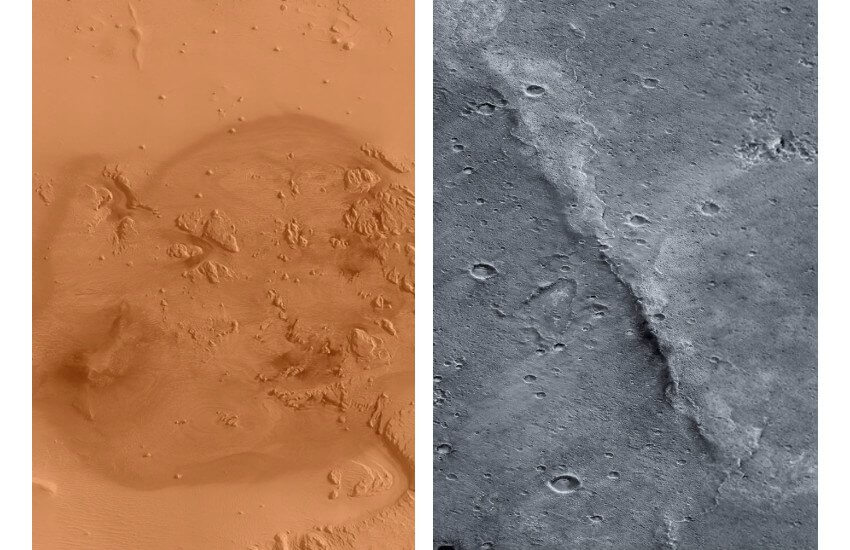

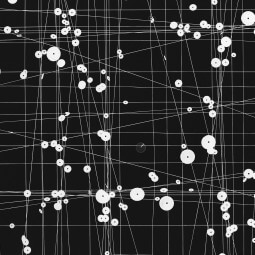

But Thomas Ruff found that the traditional photogram method was inhibitive to his process. It is time consuming, and if the composition is off the process must be started over from scratch. It also inhibits the size of the final print. So Ruff created software that simulates the photogram process. He can make changes quickly and enlarge the finished product to any dimensions. Ruff has also explored several other methods of constructing digital abstract photographic images. For his Zycles series, he used computer-modeling software to visualize mathematical processes. And in his Cassini and ma.r.s series, he combined appropriation with digital manipulation, creating abstracted astronomical landscapes that resemble what he calls Post-Suprematist compositions.

Thomas Ruff - ma.r.s 18, 2011 (Left) and Thomas Ruff - ma.r.s 11, 2010 (Right). © Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff - ma.r.s 18, 2011 (Left) and Thomas Ruff - ma.r.s 11, 2010 (Right). © Thomas Ruff

Content vs. Composition

Throughout his oeuvre, Thomas Ruff challenges the definition of authenticity and objectivity in photography. Sometimes his pieces are clearly abstract, such as with his photogram works. Other times, it is more difficult to see the abstract side of the work because we are so taken in by the scale and content of the images. But in each of his series, the unspoken subtext of the work is the central point. We are not supposed to focus on the objective image so much as we are supposed to consider the medium, the context, the perspective, and the idea.

The ultimate expression of his themes comes through in his Anderes Porträt series, for which he utilized a machine that combines police sketches to make a composite image of a face. Ruff fed the machine with photographs, creating imagined, constructed images combining male and female human faces. As with all of his work, this series is not about whether a photograph is authentic or artificial. It is not about whether it constructed or reconstructed. It is about us. It is about the way our eyes see, and the way our brains interpret what is valuable, what is possible, and what is real.

Featured image: Thomas Ruff - zycles 4080, 2009. © Thomas Ruff

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Tenesh Webber

1963

(USA)Canadian

Richard Caldicott

1962

(UK)British

Seb Janiak

1966

(France)French