Tracing the Designs of Barbara Stauffacher Solomon

Mar 25, 2019

Part artist, part dancer, and part designer, Barbara Stauffacher Solomon is best known for her work in the field of graphic. She was the mastermind behind the so-called “Super Graphics” that helped define the look of Sea Ranch, a planned community Solomon worked on in the 1960s on the northern coast of California. Today, Solomon balks at the term Super Graphics, however. When she painted her designs on the walls of Sea Ranch, she was simply providing an economical aesthetic option for the architects—a mixture of art, design, and necessity. Nonetheless, her work on the project brought her worldwide fame, and lifelong professional success. Now in her 90s, Solomon is still active in her home studio in San Francisco. In the last few years alone, she has created a massive wall mural at The UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA); produced numerous books, including a memoir; and she is currently the subject of a solo exhibition at SFMOMA, focused on her small scale graphic works, including numerous items she created for the museum over the years. In a recent interview recorded for a short documentary about her life, Solomon described the attitude she now takes towards her work as, “Very profound and very silly.” She recalls her first husband, the experimental filmmaker Frank Stauffacher. Through him, she befriended the likes of Man Ray and Hans Richter, who she refers to as “the Dada guys.” She remembers them as being brilliant, but also completely silly. “Somehow all that went into my baby head,” she says, “and now in my old age its coming out again.” Yet even if Solomon goes to great lengths not to take herself too seriously, her whimsical attitude has done nothing to diminish her legacy. Generations of artists and designers around the world have been inspired by her work, and she continues to lead her field today.

The Necessity of Design

Perhaps if Solomon could have done anything she wanted with her life, she would have been a dancer, or maybe an artist like her first husband, and so many of her friends. She became a designer out of necessity. Stauffacher died just six years into their marriage, leaving Solomon with very little income and a young daughter to raise. Having only trained as an artist and a dancer, she figured she had little chance of making a living with her existing skills. She calculated that she could, however, make a living as a graphic designer, so she moved to Basel, Switzerland, and enrolled at the Basel Art Institute. There, she studying graphics under Armin Hofmann, from whom she gained a profound appreciation for the Helvetica font. She went on to use the font in countless projects, including Sea Ranch. Hofmann also gave her the advice that helped shaped the rest of her professional life. He said, “Learn the rules. If you are brilliant, you can break all the rules. If you are not brilliant, you will be competent.”

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon - San Francisco Museum of Art program guide, March 1964, 1964. Offset lithograph. 7 x 7 in. (17.78 x 17.78 cm). Collection SFMOMA. Gift of the artist. © San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Solomon returned to the United States after hearing John F. Kennedy was going to run for President. Kennedy inspired her most idealistic nature, and made her believe she could deploy art and design to help create a more equitable world. Even the humble Helvetic font, she eagerly points out, was originally considered the most democratic. Simple, clean, and easy to read, it implied that whatever you were writing with it must be true. She calls it the graphic equivalent of Modern Architecture. And for many years after returning to the US, Solomon did use her work in ways that she felt directly or indirectly improved the lives of everyday people. But just like with the Utopian architecture of Le Corbusier, the graphic sensibilities Solomon embraced eventually symbolized capitalism, not socialism. Today, just as Modern Architecture has become almost the exclusive domain of the rich, almost every commercial entity uses Helvetica or something similar for their logo and websites. (The logo for Adobe, the company that produced her aforementioned recent documentary, exemplifies this trend.)

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon - San Francisco Museum of Art program guide, January 1968, 1967. Offset lithograph. 7 x 7 in. (17.78 x 17.78 cm). Collection SFMOMA. Gift of the artist. © San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The Need For Fun

Rather than becoming jaded about the harsh truth that art and design cannot, on its own, make the world a better place, Solomon now puts politics aside. She keeps working because it is fun: because it engages both her intellect and her sense of humor. Her recent wall mural at BAMPFA is one good example—intellectually, it converses with the existing lines of the architecture, while whimsically, Solomon says it mimics “the Rockettes kicking up.” Another example is the 2.5-mile long “Promenade Ribbon,” a raised, concrete line that follows the coast along the Embarcadero in San Francisco. Solomon collaborated on the project with Vito Acconci and Stanley Saitowitz back in 1996. Immediately after it was built, the Ribbon started getting ravaged by nature and by people. Water shorted out the electrical element that made the Ribbon light up, and skateboarders swarmed the structure, finding its multitudinous edges perfect places to grind. The damage outraged Saitowitz, but Solomon said, “I love it that the skateboarders love it,” a sentiment with which Acconci agreed.

For Solomon, the lesson embedded in the story of the “Promenade Ribbon” is the same as that embedded in the term “Super Graphics,” and in the corporate co-opting of the Helvetica font and Modern Architecture, and in the transformation of Sea Ranch from a Utopian Kibbutz to a sanctuary of second homes for multi-millionaires. The lesson is that people who create cannot control what becomes of their creations. For many artists and designers, this lesson causes high anxiety. For a time it may even have bothered Solomon, but no more. Now, watching the unintended consequences of her work unfold is just part of the fun. As Solomon recently told Sarah Hotchkiss of KQED Public Media in California, “It is very hard at a certain point to be serious. I have become seriously silly. I think that is all you can do about anything these days.”

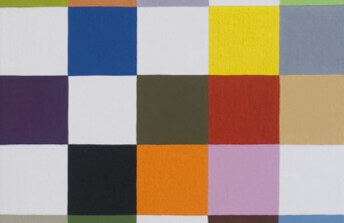

Featured image: Barbara Stauffacher Solomon - San Francisco Museum of Art program guide, July 1971, 1971. Offset lithograph. 7 x 7 in. (17.78 x 17.78 cm). Collection SFMOMA. Gift of the artist. © San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio