Celebrating 100 Years of the Bauhaus

Jan 23, 2019

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Bauhaus. Widely considered the most influential art and design school of the 20th Century, the Bauhaus was founded in Weimar, Germany, by architect Walter Gropius on 1 April 1919. Gropius was one of the leading pioneers of Modernist architecture, and of what later became known as the International Style – characterized by open floor plans and lightweight modern materials like steel and glass. Conceived in the aftermath of World War I, the Bauhaus school was intended to serve as a training ground for a new generation of artist-craftspeople, who would help create a more equitable, peaceful, and constructive future for humanity. They hoped to do this by restoring the disparate fields of art, craft and design into one cohesive discipline. Bauhaus teachers trained their students to strive not towards the creation of a building, a painting, or a sculpture, but rather to understand how buildings and paintings and sculptures come together to form a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. In his Bauhaus Manifesto, Gropius bemoaned how painting and sculpture had devolved into “salon art,” unrelatable to everyday people, and suitable only for admiration by elites. He longed for something more useful, and more interconnected with daily life. The closing paragraph of the manifesto reads, “Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist! Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.” His idealistic words stirred the imaginations of countless artists, designers and craftspeople around the world. Even though the Bauhaus only existed for 14 years, its ideas spread around the world, and its legacy continues to invoke the potentialities of the marriage of art, design and everyday life.

Utopian Dreams

While the Bauhaus Manifesto explains the practical aspects of the school – such as who should be admitted to take classes and what exactly they should study – the document does little to explain the underlying Utopian passions that inspired Gropius and his fellow Bauhaus teachers. When World War I came to a close in winter of 1918, the German people were torn between the relative benefits of a monarchy, a democratically elected representative government, or a communist-style regime. The question was partly about who should hold the power, and partly about the value of human life and the right of people to control their own fate. Eventually, a constitutional assembly took place in Weimar and a parliamentary republic was formed (The Weimar Republic), which in theory embraced the hopeful notion that individuals can work together to build a future for everyone. Progressive reforms were even passed, such as an eight-hour work day, freedom of the press, and health and retirement benefits for workers.

The Bauhaus signet

The Bauhaus was founded at nearly the same place and the same time as the republic, and was informed by many of the same issues. Bauhaus directors and teachers believed in a Utopian vision that they could transform the built world into something useful and beautiful for all people, regardless of social status. They imagined buildings that were spacious and full of sunlight, designed specifically to accommodate not institutional activities but rather the most practical aspects of daily life. Hannes Meyer, the second Bauhaus director, stated, “We examine the daily routine of everyone who lives in the house and this gives us the determining principles of the building project.” His list of priorities for designing a structure could not be more reasonable. It reads: “1. sex life, 2. sleeping habits, 3. pets, 4. gardening, 5. personal hygiene, 6. weather protection, 7. hygiene in the home, 8. car maintenance, 9. cooking, 10. heating, 11. exposure to the sun, 12. services.”

Bauhaus University Weimar. Photo by Sailko

The Great Emigration

Despite the massive influence the Bauhaus was having on global trends, when the Nazi party came into power they labeled the school “un-German,” and sympathetic to Communist ideals. The Nazis exerted pressure through the Secret Police to shut down the school. But this was not at all the end of the Bauhaus dream. Teachers and students from the school emigrated all over the world, spreading their revolutionary ideas as they went. Gropius moved to North Carolina along with Bauhaus instructors Josef and Anni Albers and joined the faculty of the Black Mountain College, and the Albers later taught at Yale. Second Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer taught and worked as an architect in Moscow, Geneva and Mexico City. Third Bauhaus director Mies van der Rohe moved to Chicago, where he headed up the Department of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology and pioneered a globally influential design aesthetic known as the Second Chicago School. Bauhaus instructor László Moholy-Nagy also moved to Chicago, where he founded “The New Bauhaus,” a school focused on “human-centered design.”

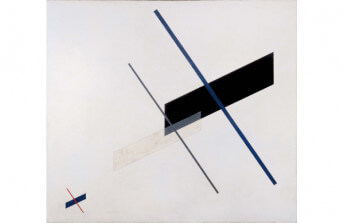

László Moholy-Nagy - A 19, 1927. Oil and graphite on canvas. 31 1/2 × 37 3/5 in. 80 × 95.5 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

It has taken Germany decades to grapple with its complicated role in the creation and rejection of the Bauhaus. Throughout 2019, museums and institutions around Germany will mount elaborate celebrations to mark the 100th anniversary of the school. While commemorating their accomplishments, we must also ask what the real legacy of these visionaries is. Should we copy their designs? Should we, as they did, attempt to create new schools of thought in an attempt to form Utopian visions for our future? Or is there a different lesson we can take from the Bauhaus. Could we perhaps acknowledge that there is some value to separating the disciplines of art, craft, design, and architecture? What seems like Utopia for one person seems like oppression to another. Maybe the value of the Bauhaus is not locked up in its utilitarian methods. Maybe its most useful message comes from the Bauhaus manifesto itself, which stated innocently enough, “Art rises above all methods.”

For a list of Bauhaus anniversary celebrations happening across Germany in 2019, visit https://www.bauhaus100.com.

Featured image: Entrance hall of the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar - in the center, below the free-swinging Art Nouveau staircase created by Auguste Rodin "Eva" (1888). Photo: Hans Weingartz.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio