A Look at the Art of Jean Le Moal

Mar 18, 2019

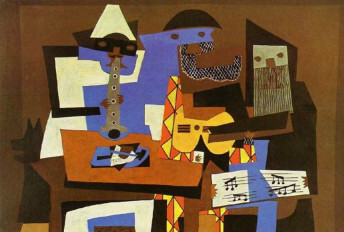

Jean Le Moal came of age as a painter in Paris in the late 1930s, just as Europe both at its cultural height and also descending into chaos. His entire career expressed echoes of this dichotomy. His art is both a testament to structure, and an acceptance of disarray. Even his earliest paintings defined Le Moal as a master colorist and an expert draughtsman. But although his early work was vivid and energetic, it was not too original. He got most of his ideas by copying the modern masters at the Louvre, and so his immature style was basically a mixture of Fauvist color, Cubist structure, and Surrealist subject matter. Le Moal was enthusiastic and brave, however, and determined that one day he would discover his unique voice. He trusted that voice would come to him through the pathways of Modernism and Abstraction. His enthusiasm for newness and experimentation brought him into the company of the French avant-garde just as the Nazis were overtaking Europe and decrying what they called “Degenerate Art.” Le Moal was one of many French artists who stood up against this censorship. During the Nazi Occupation of France, he even became a founding member of a group called the Salon de Mai (The May Salon). In addition to Le Moal, this influential collective included the art critic Gaston Diehl, as well as artists like Henri-Georges Adam, Robert Couturier, Jacques Despierre Francis Gruber, Alfred Manessier, and Gustave Singier, amongst others. The Salon de Mai formed in a cafe, and from the cafe seats the group organized a series of exhibitions over the course of several years that posed a direct challenge to their occupiers. The Salon de Mai became a beacon of light during a dark time, and helped ensure that French art would endure beyond the war. It is maybe to much to say that Le Moal and his compatriots took their belief in art to the level of a religion. However, when the war was over, Le Moal did in fact become quite dedicated to the idea that art inhabits a distinctly spiritual realm. In an attempt to create a transcendent visual voice, he dedicated himself fully to abstraction, and finally succeeded in channeling the mysterious power of color and light.

Architectural Influences

Le Moal was born in 1909 in Authon-de-Perche. His father was a civil engineer who encouraged Le Moal to take up the fields of engineering and architecture as a young man. Le Moal studied to be a sculptor in school, and specialized in low reliefs. At age 17, he enrolled at the Beaux-Arts school in Lyon as a student of architecture. It would be another two years before he finally painted his first canvases. Those first paintings were figurative works inspired by nature. And even in the mid-1930s, when Le Moal started exploring Modernist styles such as Surrealism and Cubism, his paintings showed architectonic influences. Works like “Sitting Character” (1936) and “Flora” (1938) reveal a strong attraction to structure and traditional computational harmony. His grasp of how to handle space in his art even led to one of his first breakthroughs as an artist, when Le Moal was chosen in 1939 to paint the frescoes on the ceiling of the French Pavilion at the International Exhibition in New York.

Jean Le Moal - Barques 1947. Oil on canvas. 81 x 117 cm. Private collection, Switzerland. © All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris, 2018.

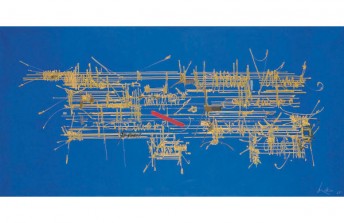

By the 1940s, Le Moal found the courage to break away from figuration, but he still remained obsessed with linear structure. In his earliest abstract works, he isolated the elements of color and line in such a way that the work resembles that of artists like Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. It was not until the 1950s that Le Moan finally found a method all his own, by completely breaking free from structure and embracing a more lyrical style. Paintings like “Spring” (1957) and “Flora” (1960) are brilliant examples of Tachisme, and even hint at the progress Le Moal was making in the spiritual realm. To make these paintings, he said that he broke free of the need to enclose things. Ironically, in 1956, at the same time as he was painting these groundbreaking works, he was also heading right back towards an interest in architecture by beginning a new career making stained glass windows for churches.

Jean Le Moal - Paysage, la ferme, 1943. Oil on canvas. 24 x 35 cm. Quimper Museum of Fine Arts. © ADAGP Paris 2018

Art as Prayer

It is hard to say which came first for Le Moan—stained glass windows or paintings that look like stained glass. Either way, his stained glass paintings embody the effect of luminous rays of color shining through splintered forms floating in space. One of the most iconic examples of his stained glass paintings is “Les Arbes” (1954). The translation means the trees, and indeed this painting hints at a view of the branches of a tree that has lost its leaves. Brilliant, colorful light fills the spaces between the lines, creating a sea of vibrant, luminous, orange and yellow forms. Like Agnes Martin, Le Moal must have seen an inherent sanctity in threes, and he likewise attempted to capture it with lines and color in paintings like “Les Arbes.”

Jean Le Moal - L'Ocean, 1958-1959. Oil on canvas. 1.62 x 1.14 m. Depot of the National Museum of Modern Art at the Quimper Museum of Fine Arts. © ADAGP Paris 2018

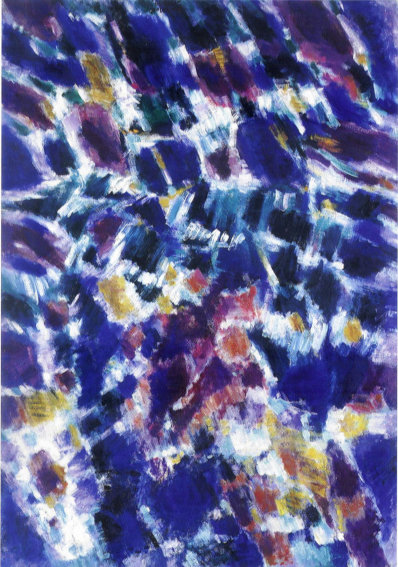

Unlike Martin, however, who was not overtly religious, Le Moal was quite open about his beliefs. He was a Christian, and his stained glass windows were installed in Christian churches. He was also hopeful that they would not only appeal to religious people. He expressed a desire to create spaces where people could pray, but also where those who do not pray can still find silence and peace. The way his stained glass window practice affected Le Moal as an artist was extraordinary. The frames of his windows are highly structured in accordance with the architecture of the churches where they are installed. But the compositions within the structures are lyrical and gestural, and highly abstract. At the same time, paintings like “Summer light” (1984-1986) show how his mature style became so loose and abstract throughout the 1970s and 80s that his paintings came to resemble tye-dye shirts, with swirling, psychedelic fields of color flowing into each other and blending with the illusionary, transcendent fields. By the end of his life, Le Moan had come full circle as an artist who could perfectly and simultaneously express the nuanced balance that exists between structure and freedom, and capture the elusive architecture of light.

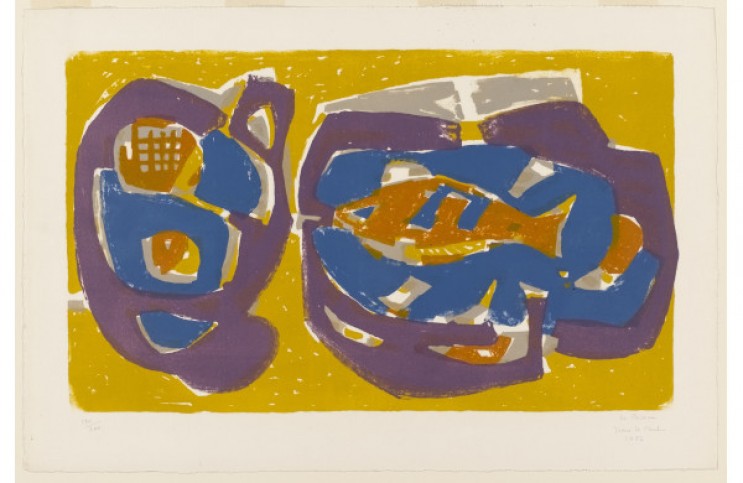

Featured image: Jean Le Moal - Fish, 1952. Lithograph. Composition: 11 3/4 x 19 11/16" (29.9 x 50cm); Sheet: 14 15/16 x 22 7/16" (38 x 57cm). Guilde de la Gravure. Larry Aldrich Fund. MoMA Collection.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio